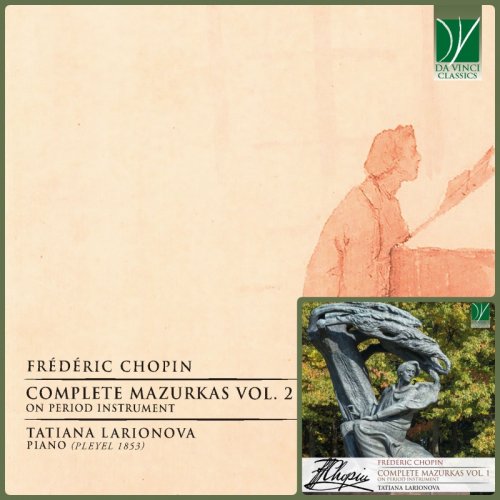

Tatiana Larionova - Frédéric Chopin: Complete Mazurkas, Vol. 1-2 (On Period Instrument) (2019-2022)

BAND/ARTIST: Tatiana Larionova

- Title: Frédéric Chopin: Complete Mazurkas, Vol. 1-2 (On Period Instrument)

- Year Of Release: 2019-2022

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical Piano

- Quality: flac lossless

- Total Time: 01:10:14 / 01:19:11

- Total Size: 216 / 277 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Mazurkas, Op. 6: No. 1 in F-Sharp Minor, —

02. Mazurkas, Op. 6: No. 2 in C-Sharp Minor, Sotto voce

03. Mazurkas, Op. 6: No. 3 in E Major, Vivace

04. Mazurkas, Op. 6: No. 4 in E-Flat Minor, Presto ma non troppo

05. Mazurkas, Op. 7: No. 5 in C Major, Vivo

06. Mazurkas, Op. 7: No. 1 in B-Flat Major, Vivace

07. Mazurkas, Op. 7: No. 2 in A Minor, Vivo, ma non troppo

08. Mazurkas, Op. 7: No. 3 in F Minor, Mazurka

09. Mazurkas, Op. 7: No. 4 in A-Flat Major, Presto

10. Mazurkas, Op. 17: No. 1 in B-Flat Major, Vivo e risoluto

11. Mazurkas, Op. 17: No. 2 in E Minor, Lento, ma non troppo

12. Mazurkas, Op. 17: No. 3 in A-Flat Major, Legato assai

13. Mazurkas, Op. 17: No. 4 in A Minor, Lento, ma non troppo

14. Mazurkas, Op. 24: No. 1 in G Minor, Lento

15. Mazurkas, Op. 24: No. 2 in C Major, Allegro non troppo

16. Mazurkas, Op. 24: No. 3 in A-Flat Major, Moderato con anima

17. Mazurkas, Op. 24: No. 4 in B-Flat Minor, Moderato

18. Mazurkas, Op. 30: No. 1 in C Minor, Allegretto non tanto

19. Mazurkas, Op. 30: No. 2 in B Minor, Allegretto

20. Mazurkas, Op. 30: No. 3 in D-Flat Major, Allegro non troppo

21. Mazurkas, Op. 30: No. 4 in C-Sharp Minor, Allegretto

22. Mazurkas, Op. 33: No. 1 in G-Sharp Minor, Mesto

23. Mazurkas, Op. 33: No. 3 in D Major, Vivace

24. Mazurkas, Op. 33: No. 2 in C Major, Semplice

25. Mazurkas, Op. 33: No. 4 in B Minor, Mesto

01. Mazurkas, Op. 41: No. 1 in E Minor, Andantino

02. Mazurkas, Op. 41: No. 2 in B Major, Animato

03. Mazurkas, Op. 41: No. 3 in A-Flat Major, Allegretto

04. Mazurkas, Op. 41: No. 4 in C-Sharp Minor, Maestoso

05. Mazurka No.50 in A Minor, Posth.

06. Mazurka No.51 in A Minor, Posth.

07. Mazurkas, Op. 50: No. 1 in G Major, Vivace

08. Mazurkas, Op. 50: No. 2 in A-Flat Major, Allegretto

09. Mazurkas, Op. 50: No. 3 in C-Sharp Minor, Moderato

10. Mazurkas, Op. 56: No. 1 in B Major, Allegro non tanto

11. Mazurkas, Op. 56: No. 2 in C Major, Vivace

12. Mazurkas, Op. 56: No. 3 in C Minor, Moderato

13. Mazurkas, Op. 59: No. 1 in A Minor, Moderato

14. Mazurkas, Op. 59: No. 2 in A-Flat Major, Allegretto

15. Mazurkas, Op. 59: No. 3 in F-Sharp Minor, Vivace

16. Mazurkas, Op. 63: No. 1 in B Major, Vivace

17. Mazurkas, Op. 63: No. 2 in F Minor, Lento

18. Mazurkas, Op. 63: No. 3 in C-Sharp Minor, Allegretto

19. Mazurka in B-Flat Major, Posth., WN 7

20. Mazurka in G Major, Posth., WN 8

21. Mazurka in A Minor, Posth., WN 14

22. Mazurka in C Major, Posth., WN 24

23. Mazurka in F Major, Posth., WN 25

24. Mazurka in G Major, Posth., WN 26

25. Mazurka in B-Flat Major, Posth., WN 41

26. Mazurka in A-Flat Major, Posth., WN 45

27. Mazurka in C Major, Posth., WN 48

28. Mazurka in A Minor, Posth., WN 60

29. Mazurka in G Minor, Posth., WN 64

30. Mazurka in F Minor, Posth., WN 65

What is a Mazurka? Well, quite obviously, it is a dance typical for the folk music of the Polish countryside. An answer such as this would reveal the speaker’s knowledge of a style and of a genre. Yet, if applied to Chopin’s Mazurkas (which are, of course, the greatest and best known of all mazurkas of the “Western” repertoire), this definition would prove, at least, debatable.

Are Mazurkas dances? Of course; yet, Chopin never meant them to be danced (even though Arthur Rubinstein, when recording Chopin’s complete Mazurkas, demonstrated the steps of the mazurka in the recording studio for the profit of the bystanders!).

Are Mazurkas folk music? Doubtlessly, the origin of the mazurka clearly belongs to Polish folk music; yet, it has been demonstrated that Chopin never employed actual folk tunes in his music. Béla Bartók argued that his Mazurkas are examples of “national” rather than of “folk” music.

Are Mazurkas “from the countryside”? Certainly, once more their roots delve deep in the Polish rural area; but it is likely that Chopin’s exposition to mazurkas happened mostly in the city of Warsaw, where mazurkas were played in the streets, and where, probably, “urbanized” forms of mazurkas were in greater demand than those actually found and played in the countryside.

Are Mazurkas… “mazurkas”? Yes and no, since Chopin did not limit himself to the typical gestures of the mazur, but also employed features from the Kujawiak (a dance typical from the region of Kujawy) and from the Oberek.

Some traits, of course, are shared by the “authentic” folk mazurkas and by Chopin’s: the ternary tempo, the typical rhythm, the abundant use of repetitions on all levels. These repetitions had originally the purpose of articulating the times and movements of dance; but even in mazurkas which were not intended for dancing (as Chopin’s), this feature is retained.

Other characteristics, instead, are unique for Chopin’s mazurkas, and are probably nowhere to be found in the folk repertoire. For instance, Chopin did not refrain from using fugato techniques (!) in his Mazurkas, or even Chorale-like writing; his harmonic wanderings are alien to the more predictable chordal structures of folk mazurkas, and his use of modality may have been influenced by some traits of the folk mazurka, but still is very much his own.

Chopin’s output of Mazurkas outnumbers all other genres in his catalogue. During his lifetime, Chopin published forty-one Mazurkas provided with opus numbers, and two individual works without opus number. Many others were published posthumously, and some – of which we know that they did exists – are currently lost. The first known Mazurka by Chopin was written when he was just fifteen; the last dates from the year of his death. For almost a quart of a century, Chopin steadily wrote Mazurkas at a rather constant pace. They therefore represent a unique possibility to observe his stylistic evolution, his personality and his genius throughout the entire arch of his compositional career. As he once wrote to his family in 1831, “My piano heard nought but mazurs”.

Generally, Chopin’s Mazurkas are brief in duration, and not excessively demanding on the pianistic level. They require a masterful handling of the tempo and rubato, a subtle sensitivity to the nuances of sound, pedalling and phrasing.

Chopin’s Mazurkas op. 41 saw the light in 1840 with a dedication to Stefan Witwicki. The order of the four Mazurkas is different in the two main “old” editions, the Parisian and the Leipzig one. Among the Mazurkas op. 41, no. 1 has a precise dating, since we possess a sketch of November 28th, 1838. At that time Chopin was in Majorca with George Sand. His nostalgia for his native land is expressed here in a touching fashion; indeed, this is one of the very few Mazurkas where a traditional theme is almost literally cited. It is a song written by Franciszek Kowalski, called Flowers sparkling on the common, which had been among the favourites during the Polish insurrections. The second Mazurka of the set opens, in Chopin’s (allegedly) own words, on the evocation of a guitar’s arpeggiated chords. In its central section, reminiscences of Polish music seem to intertwine with memories from the more recent musical experiences in Majorca. By way of contrast, the third Mazurka is quintessentially Polish, and in particular refers to musical features typical for the region of Kujawia. The fourth Mazurka is perhaps the most original of the set, with a lovely blending of poetry, song, and dance.

Different from op. 41, we have no precise dating for op. 50, except, of course, their publication date (1842). They are dedicated to the Polish patriot Leon Szmitkowski. All three pieces of the set reveal the full maturity of Chopin’s compositional idiom in the genre of the Mazurka. To be sure, references to the Polish folk tradition are clearly discernible, especially in the first Mazurka in G major, with a special presence of Kujawiak gestures. Yet, the delicate closing of this piece has nothing of the folk dances’ immediate expressivity. Kujawiak elements are also found in the second Mazurka, with its brilliant intertwining of binary and ternary tempo. The third Mazurka is perhaps the most perfect of the set, with its clever use of polyphony and its refined treatment of counterpoint. The unlikely meeting of a folk dance with the most complex compositional techniques of the Western tradition is masterfully handled by Chopin, who does not turn his compositional mastery into pedantry, but rather employs it for exquisitely expressive purposes.

The set of three Mazurkas op. 56 was achieved in 1843, and these are among the finest examples of Chopin’s handling of this genre. Here again we find polyphony, but with a less serious and more personal character. It is as if each of the voices would represent a personality, entering in dialogue with another. In marked contrast, the second Mazurka is deliberately marked by peasant features. In Ferdynand Hoesick’s brilliant definition, “The basses bellow, the strings go hell for leather, the lads dance with the lasses and they all but wreck the inn”. In fact, the overall atmosphere is determined more by the sound of rural music than by actual quotes from melodies and tunes. Here again we find elements of the Kujawiak, combining with each other in a very creative fashion. An entirely different atmosphere characterizes op. 56 no. 3, with its expressive elegance and its beautifully crafted structure in terms of form and harmony.

Op. 59 opens in hushed tones, with the secretive and confidential enunciation of the first theme; later, the first Mazurka of this set of three will include a number of different themes, each and all possessing a musical individuality of its own. A markedly narrative character is found in the second Mazurka, which has a deeply expressive dimension, as if from afar. In 1844, the autograph of this Mazurka was sent by Chopin to Mendelssohn, on the latter’s request, as a wedding gift for Mendelssohn’s bride. The third Mazurka involves both player and hearers in an enthralling dance, whereby moments of musical frenzy alternate with subdued passages, necessary for building up the passionate climaxes.

Op. 63 opens with an enigmatic Mazurka, initially showing a plainly, robustly mazur rhythm, but then revealing a great depth of conflicting emotions and delicate feelings. The following piece, instead, is entirely pervaded by a sentiment of longing and yearning, and represents a kind of intimate confession. By way of contrast, the final Mazurka is full of cantabile and expressivity – at times subdued, at times more openly proclaimed.

The two Mazurkas characterized by the indication “Dbop.” were published during Chopin’s lifetime, but unprovided with an opus number. That indicated as Dbop. 42A was written in 1840 and is dedicated to Emile Gaillard. Indeed, this piece can hardly be defined as a Mazurka at all, since it lacks all the “folklike” features displayed in other examples of this genre. But, as we said at the beginning, Chopin’s Mazurkas are Chopin’s Mazurkas.

Mazurka Dbop. 42B belongs in a collection of Morceaux de salon, published by the magazine Notre temps, and including pieces written by different composers among whom Chopin, but also Czerny, Rosenheim and Thalberg. Yet, Chopin’s Mazurka does not correspond to the rather superficial canons of salon music, with its expressive depth and intense, intimate character.

B-flat major Mazurka WN 7, along with the G-major Mazurka WN 8, are youthful works, dating 1825-6; however, Chopin’s periodizing is fascinating and already reveals his unique personality. A quintessentially Chopinesque melancholia is found in the A-minor Mazurka WN 14, just a couple of years after the preceding ones; a much more boisterous style characterizes WN 24, with its powerful chords in the “open” key of C major. WN 25 completes the set which had been published in Germany by Schlesinger as op. 68, and offers us a generous abundance of expressive means.

Mazurka WN 26 was published as op. 67 no. 1, and was written in 1835. It is a simple, straightforward piece, written as a homage to a young Polish lady. By way of contrast, even if Mazurka WN 45 is found in an album once belonging to Maria Szymanowska, it is likely that Chopin wrote it for her daughter. Another lady, a Mrs. Hoffmann, is the dedicatee of Mazurka WN 48, published posthumously as op. 67 no. 3, whilst WN 60, published as op. 67 no. 4 by Fontana, is a small gem of interior profundity and poetry.

Together, the Mazurkas recorded here truly represent the multifaceted creative genius of Chopin, the variety of his moods, the richness of his personality, and lead us into a journey at the discovery of his Polishness, and of his refined musicianship.

01. Mazurkas, Op. 6: No. 1 in F-Sharp Minor, —

02. Mazurkas, Op. 6: No. 2 in C-Sharp Minor, Sotto voce

03. Mazurkas, Op. 6: No. 3 in E Major, Vivace

04. Mazurkas, Op. 6: No. 4 in E-Flat Minor, Presto ma non troppo

05. Mazurkas, Op. 7: No. 5 in C Major, Vivo

06. Mazurkas, Op. 7: No. 1 in B-Flat Major, Vivace

07. Mazurkas, Op. 7: No. 2 in A Minor, Vivo, ma non troppo

08. Mazurkas, Op. 7: No. 3 in F Minor, Mazurka

09. Mazurkas, Op. 7: No. 4 in A-Flat Major, Presto

10. Mazurkas, Op. 17: No. 1 in B-Flat Major, Vivo e risoluto

11. Mazurkas, Op. 17: No. 2 in E Minor, Lento, ma non troppo

12. Mazurkas, Op. 17: No. 3 in A-Flat Major, Legato assai

13. Mazurkas, Op. 17: No. 4 in A Minor, Lento, ma non troppo

14. Mazurkas, Op. 24: No. 1 in G Minor, Lento

15. Mazurkas, Op. 24: No. 2 in C Major, Allegro non troppo

16. Mazurkas, Op. 24: No. 3 in A-Flat Major, Moderato con anima

17. Mazurkas, Op. 24: No. 4 in B-Flat Minor, Moderato

18. Mazurkas, Op. 30: No. 1 in C Minor, Allegretto non tanto

19. Mazurkas, Op. 30: No. 2 in B Minor, Allegretto

20. Mazurkas, Op. 30: No. 3 in D-Flat Major, Allegro non troppo

21. Mazurkas, Op. 30: No. 4 in C-Sharp Minor, Allegretto

22. Mazurkas, Op. 33: No. 1 in G-Sharp Minor, Mesto

23. Mazurkas, Op. 33: No. 3 in D Major, Vivace

24. Mazurkas, Op. 33: No. 2 in C Major, Semplice

25. Mazurkas, Op. 33: No. 4 in B Minor, Mesto

01. Mazurkas, Op. 41: No. 1 in E Minor, Andantino

02. Mazurkas, Op. 41: No. 2 in B Major, Animato

03. Mazurkas, Op. 41: No. 3 in A-Flat Major, Allegretto

04. Mazurkas, Op. 41: No. 4 in C-Sharp Minor, Maestoso

05. Mazurka No.50 in A Minor, Posth.

06. Mazurka No.51 in A Minor, Posth.

07. Mazurkas, Op. 50: No. 1 in G Major, Vivace

08. Mazurkas, Op. 50: No. 2 in A-Flat Major, Allegretto

09. Mazurkas, Op. 50: No. 3 in C-Sharp Minor, Moderato

10. Mazurkas, Op. 56: No. 1 in B Major, Allegro non tanto

11. Mazurkas, Op. 56: No. 2 in C Major, Vivace

12. Mazurkas, Op. 56: No. 3 in C Minor, Moderato

13. Mazurkas, Op. 59: No. 1 in A Minor, Moderato

14. Mazurkas, Op. 59: No. 2 in A-Flat Major, Allegretto

15. Mazurkas, Op. 59: No. 3 in F-Sharp Minor, Vivace

16. Mazurkas, Op. 63: No. 1 in B Major, Vivace

17. Mazurkas, Op. 63: No. 2 in F Minor, Lento

18. Mazurkas, Op. 63: No. 3 in C-Sharp Minor, Allegretto

19. Mazurka in B-Flat Major, Posth., WN 7

20. Mazurka in G Major, Posth., WN 8

21. Mazurka in A Minor, Posth., WN 14

22. Mazurka in C Major, Posth., WN 24

23. Mazurka in F Major, Posth., WN 25

24. Mazurka in G Major, Posth., WN 26

25. Mazurka in B-Flat Major, Posth., WN 41

26. Mazurka in A-Flat Major, Posth., WN 45

27. Mazurka in C Major, Posth., WN 48

28. Mazurka in A Minor, Posth., WN 60

29. Mazurka in G Minor, Posth., WN 64

30. Mazurka in F Minor, Posth., WN 65

What is a Mazurka? Well, quite obviously, it is a dance typical for the folk music of the Polish countryside. An answer such as this would reveal the speaker’s knowledge of a style and of a genre. Yet, if applied to Chopin’s Mazurkas (which are, of course, the greatest and best known of all mazurkas of the “Western” repertoire), this definition would prove, at least, debatable.

Are Mazurkas dances? Of course; yet, Chopin never meant them to be danced (even though Arthur Rubinstein, when recording Chopin’s complete Mazurkas, demonstrated the steps of the mazurka in the recording studio for the profit of the bystanders!).

Are Mazurkas folk music? Doubtlessly, the origin of the mazurka clearly belongs to Polish folk music; yet, it has been demonstrated that Chopin never employed actual folk tunes in his music. Béla Bartók argued that his Mazurkas are examples of “national” rather than of “folk” music.

Are Mazurkas “from the countryside”? Certainly, once more their roots delve deep in the Polish rural area; but it is likely that Chopin’s exposition to mazurkas happened mostly in the city of Warsaw, where mazurkas were played in the streets, and where, probably, “urbanized” forms of mazurkas were in greater demand than those actually found and played in the countryside.

Are Mazurkas… “mazurkas”? Yes and no, since Chopin did not limit himself to the typical gestures of the mazur, but also employed features from the Kujawiak (a dance typical from the region of Kujawy) and from the Oberek.

Some traits, of course, are shared by the “authentic” folk mazurkas and by Chopin’s: the ternary tempo, the typical rhythm, the abundant use of repetitions on all levels. These repetitions had originally the purpose of articulating the times and movements of dance; but even in mazurkas which were not intended for dancing (as Chopin’s), this feature is retained.

Other characteristics, instead, are unique for Chopin’s mazurkas, and are probably nowhere to be found in the folk repertoire. For instance, Chopin did not refrain from using fugato techniques (!) in his Mazurkas, or even Chorale-like writing; his harmonic wanderings are alien to the more predictable chordal structures of folk mazurkas, and his use of modality may have been influenced by some traits of the folk mazurka, but still is very much his own.

Chopin’s output of Mazurkas outnumbers all other genres in his catalogue. During his lifetime, Chopin published forty-one Mazurkas provided with opus numbers, and two individual works without opus number. Many others were published posthumously, and some – of which we know that they did exists – are currently lost. The first known Mazurka by Chopin was written when he was just fifteen; the last dates from the year of his death. For almost a quart of a century, Chopin steadily wrote Mazurkas at a rather constant pace. They therefore represent a unique possibility to observe his stylistic evolution, his personality and his genius throughout the entire arch of his compositional career. As he once wrote to his family in 1831, “My piano heard nought but mazurs”.

Generally, Chopin’s Mazurkas are brief in duration, and not excessively demanding on the pianistic level. They require a masterful handling of the tempo and rubato, a subtle sensitivity to the nuances of sound, pedalling and phrasing.

Chopin’s Mazurkas op. 41 saw the light in 1840 with a dedication to Stefan Witwicki. The order of the four Mazurkas is different in the two main “old” editions, the Parisian and the Leipzig one. Among the Mazurkas op. 41, no. 1 has a precise dating, since we possess a sketch of November 28th, 1838. At that time Chopin was in Majorca with George Sand. His nostalgia for his native land is expressed here in a touching fashion; indeed, this is one of the very few Mazurkas where a traditional theme is almost literally cited. It is a song written by Franciszek Kowalski, called Flowers sparkling on the common, which had been among the favourites during the Polish insurrections. The second Mazurka of the set opens, in Chopin’s (allegedly) own words, on the evocation of a guitar’s arpeggiated chords. In its central section, reminiscences of Polish music seem to intertwine with memories from the more recent musical experiences in Majorca. By way of contrast, the third Mazurka is quintessentially Polish, and in particular refers to musical features typical for the region of Kujawia. The fourth Mazurka is perhaps the most original of the set, with a lovely blending of poetry, song, and dance.

Different from op. 41, we have no precise dating for op. 50, except, of course, their publication date (1842). They are dedicated to the Polish patriot Leon Szmitkowski. All three pieces of the set reveal the full maturity of Chopin’s compositional idiom in the genre of the Mazurka. To be sure, references to the Polish folk tradition are clearly discernible, especially in the first Mazurka in G major, with a special presence of Kujawiak gestures. Yet, the delicate closing of this piece has nothing of the folk dances’ immediate expressivity. Kujawiak elements are also found in the second Mazurka, with its brilliant intertwining of binary and ternary tempo. The third Mazurka is perhaps the most perfect of the set, with its clever use of polyphony and its refined treatment of counterpoint. The unlikely meeting of a folk dance with the most complex compositional techniques of the Western tradition is masterfully handled by Chopin, who does not turn his compositional mastery into pedantry, but rather employs it for exquisitely expressive purposes.

The set of three Mazurkas op. 56 was achieved in 1843, and these are among the finest examples of Chopin’s handling of this genre. Here again we find polyphony, but with a less serious and more personal character. It is as if each of the voices would represent a personality, entering in dialogue with another. In marked contrast, the second Mazurka is deliberately marked by peasant features. In Ferdynand Hoesick’s brilliant definition, “The basses bellow, the strings go hell for leather, the lads dance with the lasses and they all but wreck the inn”. In fact, the overall atmosphere is determined more by the sound of rural music than by actual quotes from melodies and tunes. Here again we find elements of the Kujawiak, combining with each other in a very creative fashion. An entirely different atmosphere characterizes op. 56 no. 3, with its expressive elegance and its beautifully crafted structure in terms of form and harmony.

Op. 59 opens in hushed tones, with the secretive and confidential enunciation of the first theme; later, the first Mazurka of this set of three will include a number of different themes, each and all possessing a musical individuality of its own. A markedly narrative character is found in the second Mazurka, which has a deeply expressive dimension, as if from afar. In 1844, the autograph of this Mazurka was sent by Chopin to Mendelssohn, on the latter’s request, as a wedding gift for Mendelssohn’s bride. The third Mazurka involves both player and hearers in an enthralling dance, whereby moments of musical frenzy alternate with subdued passages, necessary for building up the passionate climaxes.

Op. 63 opens with an enigmatic Mazurka, initially showing a plainly, robustly mazur rhythm, but then revealing a great depth of conflicting emotions and delicate feelings. The following piece, instead, is entirely pervaded by a sentiment of longing and yearning, and represents a kind of intimate confession. By way of contrast, the final Mazurka is full of cantabile and expressivity – at times subdued, at times more openly proclaimed.

The two Mazurkas characterized by the indication “Dbop.” were published during Chopin’s lifetime, but unprovided with an opus number. That indicated as Dbop. 42A was written in 1840 and is dedicated to Emile Gaillard. Indeed, this piece can hardly be defined as a Mazurka at all, since it lacks all the “folklike” features displayed in other examples of this genre. But, as we said at the beginning, Chopin’s Mazurkas are Chopin’s Mazurkas.

Mazurka Dbop. 42B belongs in a collection of Morceaux de salon, published by the magazine Notre temps, and including pieces written by different composers among whom Chopin, but also Czerny, Rosenheim and Thalberg. Yet, Chopin’s Mazurka does not correspond to the rather superficial canons of salon music, with its expressive depth and intense, intimate character.

B-flat major Mazurka WN 7, along with the G-major Mazurka WN 8, are youthful works, dating 1825-6; however, Chopin’s periodizing is fascinating and already reveals his unique personality. A quintessentially Chopinesque melancholia is found in the A-minor Mazurka WN 14, just a couple of years after the preceding ones; a much more boisterous style characterizes WN 24, with its powerful chords in the “open” key of C major. WN 25 completes the set which had been published in Germany by Schlesinger as op. 68, and offers us a generous abundance of expressive means.

Mazurka WN 26 was published as op. 67 no. 1, and was written in 1835. It is a simple, straightforward piece, written as a homage to a young Polish lady. By way of contrast, even if Mazurka WN 45 is found in an album once belonging to Maria Szymanowska, it is likely that Chopin wrote it for her daughter. Another lady, a Mrs. Hoffmann, is the dedicatee of Mazurka WN 48, published posthumously as op. 67 no. 3, whilst WN 60, published as op. 67 no. 4 by Fontana, is a small gem of interior profundity and poetry.

Together, the Mazurkas recorded here truly represent the multifaceted creative genius of Chopin, the variety of his moods, the richness of his personality, and lead us into a journey at the discovery of his Polishness, and of his refined musicianship.

Year 2022 | Year 2019 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads