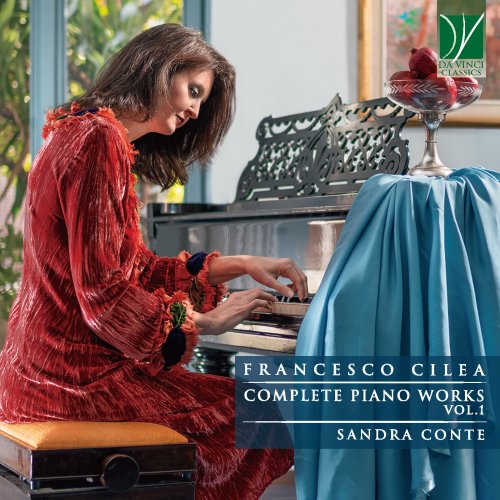

Sandra Conte - Francesco Cilea: Complete Piano Works - Vol. 1 (2022)

BAND/ARTIST: Sandra Conte

- Title: Francesco Cilea: Complete Piano Works - Vol. 1

- Year Of Release: 2022

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical Piano

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:04:58

- Total Size: 248 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Mazurka

02. Preludio

03. Valzer, Op. 36

04. Notturno, Op. 22

05. Mazurka, Op. 14

06. Gocce di rugiada, Op. 33

07. Au Village, Op. 34

08. Scherzando

09. Vespero

10. Flatterie, Op. 11

11. C'est toi que j'aime, Op. 10

12. Tre piccoli pezzi: No. 1, Melodia

13. Tre piccoli pezzi: No. 2, Serenata

14. Tre piccoli pezzi: No. 3, Danza

15. Impromptu

16. Tre pezzi, Op. 29: No. 1, Romanza

17. Tre pezzi, Op. 29: No. 2, Scherzino

18. Tre pezzi, Op. 29: No. 3, Barzelletta

19. Trois petits morceaux, Op. 28: No. 1, Loin dans la mer

20. Trois petits morceaux, Op. 28: No. 2, Feuille d’album

21. Trois petits morceaux, Op. 28: No. 3, Pensée espagnole

22. Suite, Op. 42: I. Allegro

23. Suite, Op. 42: II. Sarabanda

24. Suite, Op. 42: III. Capriccio

25. Badinage, Op. 15

26. Chanson du rouet, Op. 4

27. Foglio d'album

28. Seconda Danza, Op. 26

There is a handful of composers, in the history of Western music, whose name is inseparably and indissolubly associated to just one work, and frequently that work is an opera. This happens, for instance, with Leoncavallo’s I Pagliacci, with Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana, with Giordano’s Andrea Chénier… and with Francesco Cilea’s Adriana Lecouvreur.

Yet, each and every musician cited in this list may have achieved immortality thanks to his one absolute masterwork, but contributed valuable compositions to the history of music; and if it may happen that just that one work is truly outstanding, normally the others are at least very interesting, and at times genuinely beautiful.

Moreover, given the cultural climate in Italy between nineteenth and twentieth century, instrumental music still had to struggle in order to conquer its place in the audience’s ears. So it happens that some truly excellent Italian composers who wrote no operas are practically forgotten, both in Italy and abroad; and those who did venture in the operatic field have their instrumental output completely overshadowed by their operatic feats. The latter is the case with Francesco Cilea, the protagonist of this recording of his complete piano works.

Cilea was certainly fully entitled to write beautiful piano music, since he was an appreciated pianist himself. He was born in Palmi on July 23rd, 1866. Palmi is a small city near Reggio Calabria, at the southernmost border of the Italian peninsula, just a few kilometers from the island of Sicily. His father, Giuseppe, was a lawyer and a music amateur. At the age of seven, Francesco was sent to the most important city in the South of the recently established kingdom of Italy, i.e. Naples, where he attended a boarding school. Even though the path laid before him was that of following in his father’s footsteps (i.e., to become a lawyer in turn), Francesco felt a much greater inclination for what was his father’s hobby, i.e. music. The child soon demonstrated great musical talent and fresh inspiration in the field of improvisation. Thus, he was encouraged to pursue a thorough musical training, with the blessing of Francesco Florimo, the legendary librarian of the Neapolitan Conservatory.

At first, Francesco’s family was very perplexed by the idea of a musical career; however, at the age of 12, the child was eventually allowed to follow his genius, and to attend the Conservatory of Naples, at first as a paying student, but very soon as the recipient of a scholarship. His teachers were Beniamino Cesi, a pianist and pedagogue whose piano methods are still in use today, and Paolo Serrao, who initiated the teenager to the secrets of composition. Even before he completed his formal training, Cilea was invited to teach at the institution in a role similar to that of a teaching assistant. The last years of his piano education were guided by another major figure of the Italian musical culture and pianism, i.e. Giuseppe Martucci, one of the great piano virtuosos of the era and an exponent of the group of Italian composers whose best creations are in the field of instrumental music.

For his diploma in composition, Cilea presented a complete opera, which was premiered at the Conservatory to great acclaim. The reviewers easily foresaw a promising future for the young musician. Immediately after his diploma, Cilea was appointed a professor of harmony and of piano as a second instrument; however, he would not maintain this job for a long time, since his true calling was for the operatic stage, and he wished to devote his energies fully to that creative activity.

A first commission came rather soon, when music publisher Sonzogno asked him to write an opera on a libretto by Angelo Zanardini, by the title of La Tilda. The subject did not correspond to Cilea’s personality, but he gave his best and the opera was an immediate success, running from Florence to many other Italian cities, and even to Vienna. It may be worth mentioning that Eduard Hanslick, the bête noire of Wagner, that critic of critics who certainly was not known for his generosity in his praises, was enthused by the work. In spite of all this, Cilea, who was very exacting and hard to please, felt dissatisfied with his own opera, and retired it from the stages.

He then wrote his own version of L’Arlesiana (on the same subject as Bizet’s), whose premiere was entrusted to an Enrico Caruso at his debut. Cilea’s true consecration came however, with Adriana Lecouvreur, which, as has been said, is still “the” opera written by Cilea, and is regularly heard on the stages of the major opera theaters all over the world. Another opera, Gloria, did not meet with comparable success, and is today virtually forgotten; his last opera, Il matrimonio selvaggio (1909), remained unpublished. The last decades of Cilea’s life passed therefore at some distance from the operatic stage. He taught and had positions of responsibility at some of the major Italian conservatories, and he continued to compose.

The paradox is therefore that Cilea’s career as an operatic composer did not reach the two decades, and still he is known mainly as the creator of Adriana Lecouvreur; by way of contrast, his activity as a composer of piano pieces extends over more than six (!) decades, from the Scherzo he wrote as early as 1883, until the Piccola Suite, dating from a mere three years before his death. If some of Cilea’s earliest piano works, such as his Notturno and Mazurka were written when the composer was not yet ten years old, many others were conceived for his students. Through these pieces, he was able to instill both technical and musical values in his students and to educate them pleasurably. For this reason, these works should find their place also in today’s piano courses, and it is to be wished that the publication of the present recording will help Cilea’s music to find a place in the teaching curricula.

Another valuable aspect of Cilea’s works, and particularly of those written in mature age, is their frequent literary inspiration. Among the poets cited in his music is Rabindranatah Tagore, whose verses are cited in Cilea’s Invocazione (1923).

Several of the pieces performed here have highly evocative titles: for instance, “Gocce di rugiada” is the musical representation of “dewdrops”. Other works, particularly among those written in the composer’s youthful years, reveal the influence of Chopin: from the earliest Mazurka of 1880 to the later work by the same name, published as op. 14, from the Preludio of 1886 to the Notturno published as op. 22, the importance of Chopin as a model and as a source of inspiration is evident. On the other hand, the Scherzando written in 1883 reveals the budding composer’s interest in the music of Robert Schumann. Moreover, the Notturno op. 22 does allude to Chopin, but with the already-formed style of a mature composer. Young Cilea clearly absorbed the teaching and values of his professor Martucci, both as a pianist and as a composer; it has been argued that this work is also indebted to the technique, style, and musicianship of Sigismund Thalberg, whose stay in Posillipo would prove crucial for the development of the Italian piano school and for the dissemination of “northern” instrumental music in the Peninsula.

Conversely, the instrumental works of the most promising Italian musicians were appreciated outside Italy more than within its borders. For instance, Cilea’s Trois petits morceaux op. 28, written in 1895, saw the light in Berlin, where they were published by Bote & Bock in 1898. This small collection, whose French titles reveal their composer’s claim to an international status, are particularly interesting for the use of harmony which manages to find a balance between Cilea’s rootedness in the tonal tradition and his attention to the transalpine trends. Just as his operas demonstrate a fruitful dialogue with the French tradition of, for instance, Jules Massenet, here too he seems to provide an Italian response to the symbolists’ exploration of the piano’s sonorities. Similar experiments are observed in the interesting Badinage op. 15, with its tonal wavering and original combinations of sound and technique.

Both Cesi and Martucci were among the first appreciators of Bach in Italy, and they also contributed to the rediscovery of the Italian heritage of Baroque music. Evidently, their lesson was not lost on Cilea, who, in his Suite (Vecchio stile) op. 42 offers his own, personal and original, reinterpretation of the styles and musical gestures of the past. The result is far from the antiquarian reconstruction of a lost language; rather, Cilea nods to the virtuoso pianists of his time with the brilliant Capriccio found at the Suite’s end. Among the many other works comprised in this recording, the Chanson du rouet (Song of the Spinning Wheel) is worth mentioning. Written toward the end of the nineteenth century, it has a markedly descriptive quality, and clearly alludes to the famous, onomatopoeic depictions of the activity of spinning in the Romantic repertoire (as found in Schubert and Mendelssohn). Yet, Cilea manages to find a voice of his own, here and in the other works recorded in this album.

The long itinerary of his pianism is therefore to be considered as a journal documenting his creative life, his reactions to the various styles of the era, the musical and extra-musical interests of their composer. By listening to this album, we are drawn into the musician’s personal life, and can assist, in a manner of speaking, to the blossoming, flowering, and ripening of his talent, which, at each stage of his life, had something beautiful to offer.

01. Mazurka

02. Preludio

03. Valzer, Op. 36

04. Notturno, Op. 22

05. Mazurka, Op. 14

06. Gocce di rugiada, Op. 33

07. Au Village, Op. 34

08. Scherzando

09. Vespero

10. Flatterie, Op. 11

11. C'est toi que j'aime, Op. 10

12. Tre piccoli pezzi: No. 1, Melodia

13. Tre piccoli pezzi: No. 2, Serenata

14. Tre piccoli pezzi: No. 3, Danza

15. Impromptu

16. Tre pezzi, Op. 29: No. 1, Romanza

17. Tre pezzi, Op. 29: No. 2, Scherzino

18. Tre pezzi, Op. 29: No. 3, Barzelletta

19. Trois petits morceaux, Op. 28: No. 1, Loin dans la mer

20. Trois petits morceaux, Op. 28: No. 2, Feuille d’album

21. Trois petits morceaux, Op. 28: No. 3, Pensée espagnole

22. Suite, Op. 42: I. Allegro

23. Suite, Op. 42: II. Sarabanda

24. Suite, Op. 42: III. Capriccio

25. Badinage, Op. 15

26. Chanson du rouet, Op. 4

27. Foglio d'album

28. Seconda Danza, Op. 26

There is a handful of composers, in the history of Western music, whose name is inseparably and indissolubly associated to just one work, and frequently that work is an opera. This happens, for instance, with Leoncavallo’s I Pagliacci, with Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana, with Giordano’s Andrea Chénier… and with Francesco Cilea’s Adriana Lecouvreur.

Yet, each and every musician cited in this list may have achieved immortality thanks to his one absolute masterwork, but contributed valuable compositions to the history of music; and if it may happen that just that one work is truly outstanding, normally the others are at least very interesting, and at times genuinely beautiful.

Moreover, given the cultural climate in Italy between nineteenth and twentieth century, instrumental music still had to struggle in order to conquer its place in the audience’s ears. So it happens that some truly excellent Italian composers who wrote no operas are practically forgotten, both in Italy and abroad; and those who did venture in the operatic field have their instrumental output completely overshadowed by their operatic feats. The latter is the case with Francesco Cilea, the protagonist of this recording of his complete piano works.

Cilea was certainly fully entitled to write beautiful piano music, since he was an appreciated pianist himself. He was born in Palmi on July 23rd, 1866. Palmi is a small city near Reggio Calabria, at the southernmost border of the Italian peninsula, just a few kilometers from the island of Sicily. His father, Giuseppe, was a lawyer and a music amateur. At the age of seven, Francesco was sent to the most important city in the South of the recently established kingdom of Italy, i.e. Naples, where he attended a boarding school. Even though the path laid before him was that of following in his father’s footsteps (i.e., to become a lawyer in turn), Francesco felt a much greater inclination for what was his father’s hobby, i.e. music. The child soon demonstrated great musical talent and fresh inspiration in the field of improvisation. Thus, he was encouraged to pursue a thorough musical training, with the blessing of Francesco Florimo, the legendary librarian of the Neapolitan Conservatory.

At first, Francesco’s family was very perplexed by the idea of a musical career; however, at the age of 12, the child was eventually allowed to follow his genius, and to attend the Conservatory of Naples, at first as a paying student, but very soon as the recipient of a scholarship. His teachers were Beniamino Cesi, a pianist and pedagogue whose piano methods are still in use today, and Paolo Serrao, who initiated the teenager to the secrets of composition. Even before he completed his formal training, Cilea was invited to teach at the institution in a role similar to that of a teaching assistant. The last years of his piano education were guided by another major figure of the Italian musical culture and pianism, i.e. Giuseppe Martucci, one of the great piano virtuosos of the era and an exponent of the group of Italian composers whose best creations are in the field of instrumental music.

For his diploma in composition, Cilea presented a complete opera, which was premiered at the Conservatory to great acclaim. The reviewers easily foresaw a promising future for the young musician. Immediately after his diploma, Cilea was appointed a professor of harmony and of piano as a second instrument; however, he would not maintain this job for a long time, since his true calling was for the operatic stage, and he wished to devote his energies fully to that creative activity.

A first commission came rather soon, when music publisher Sonzogno asked him to write an opera on a libretto by Angelo Zanardini, by the title of La Tilda. The subject did not correspond to Cilea’s personality, but he gave his best and the opera was an immediate success, running from Florence to many other Italian cities, and even to Vienna. It may be worth mentioning that Eduard Hanslick, the bête noire of Wagner, that critic of critics who certainly was not known for his generosity in his praises, was enthused by the work. In spite of all this, Cilea, who was very exacting and hard to please, felt dissatisfied with his own opera, and retired it from the stages.

He then wrote his own version of L’Arlesiana (on the same subject as Bizet’s), whose premiere was entrusted to an Enrico Caruso at his debut. Cilea’s true consecration came however, with Adriana Lecouvreur, which, as has been said, is still “the” opera written by Cilea, and is regularly heard on the stages of the major opera theaters all over the world. Another opera, Gloria, did not meet with comparable success, and is today virtually forgotten; his last opera, Il matrimonio selvaggio (1909), remained unpublished. The last decades of Cilea’s life passed therefore at some distance from the operatic stage. He taught and had positions of responsibility at some of the major Italian conservatories, and he continued to compose.

The paradox is therefore that Cilea’s career as an operatic composer did not reach the two decades, and still he is known mainly as the creator of Adriana Lecouvreur; by way of contrast, his activity as a composer of piano pieces extends over more than six (!) decades, from the Scherzo he wrote as early as 1883, until the Piccola Suite, dating from a mere three years before his death. If some of Cilea’s earliest piano works, such as his Notturno and Mazurka were written when the composer was not yet ten years old, many others were conceived for his students. Through these pieces, he was able to instill both technical and musical values in his students and to educate them pleasurably. For this reason, these works should find their place also in today’s piano courses, and it is to be wished that the publication of the present recording will help Cilea’s music to find a place in the teaching curricula.

Another valuable aspect of Cilea’s works, and particularly of those written in mature age, is their frequent literary inspiration. Among the poets cited in his music is Rabindranatah Tagore, whose verses are cited in Cilea’s Invocazione (1923).

Several of the pieces performed here have highly evocative titles: for instance, “Gocce di rugiada” is the musical representation of “dewdrops”. Other works, particularly among those written in the composer’s youthful years, reveal the influence of Chopin: from the earliest Mazurka of 1880 to the later work by the same name, published as op. 14, from the Preludio of 1886 to the Notturno published as op. 22, the importance of Chopin as a model and as a source of inspiration is evident. On the other hand, the Scherzando written in 1883 reveals the budding composer’s interest in the music of Robert Schumann. Moreover, the Notturno op. 22 does allude to Chopin, but with the already-formed style of a mature composer. Young Cilea clearly absorbed the teaching and values of his professor Martucci, both as a pianist and as a composer; it has been argued that this work is also indebted to the technique, style, and musicianship of Sigismund Thalberg, whose stay in Posillipo would prove crucial for the development of the Italian piano school and for the dissemination of “northern” instrumental music in the Peninsula.

Conversely, the instrumental works of the most promising Italian musicians were appreciated outside Italy more than within its borders. For instance, Cilea’s Trois petits morceaux op. 28, written in 1895, saw the light in Berlin, where they were published by Bote & Bock in 1898. This small collection, whose French titles reveal their composer’s claim to an international status, are particularly interesting for the use of harmony which manages to find a balance between Cilea’s rootedness in the tonal tradition and his attention to the transalpine trends. Just as his operas demonstrate a fruitful dialogue with the French tradition of, for instance, Jules Massenet, here too he seems to provide an Italian response to the symbolists’ exploration of the piano’s sonorities. Similar experiments are observed in the interesting Badinage op. 15, with its tonal wavering and original combinations of sound and technique.

Both Cesi and Martucci were among the first appreciators of Bach in Italy, and they also contributed to the rediscovery of the Italian heritage of Baroque music. Evidently, their lesson was not lost on Cilea, who, in his Suite (Vecchio stile) op. 42 offers his own, personal and original, reinterpretation of the styles and musical gestures of the past. The result is far from the antiquarian reconstruction of a lost language; rather, Cilea nods to the virtuoso pianists of his time with the brilliant Capriccio found at the Suite’s end. Among the many other works comprised in this recording, the Chanson du rouet (Song of the Spinning Wheel) is worth mentioning. Written toward the end of the nineteenth century, it has a markedly descriptive quality, and clearly alludes to the famous, onomatopoeic depictions of the activity of spinning in the Romantic repertoire (as found in Schubert and Mendelssohn). Yet, Cilea manages to find a voice of his own, here and in the other works recorded in this album.

The long itinerary of his pianism is therefore to be considered as a journal documenting his creative life, his reactions to the various styles of the era, the musical and extra-musical interests of their composer. By listening to this album, we are drawn into the musician’s personal life, and can assist, in a manner of speaking, to the blossoming, flowering, and ripening of his talent, which, at each stage of his life, had something beautiful to offer.

Year 2022 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads