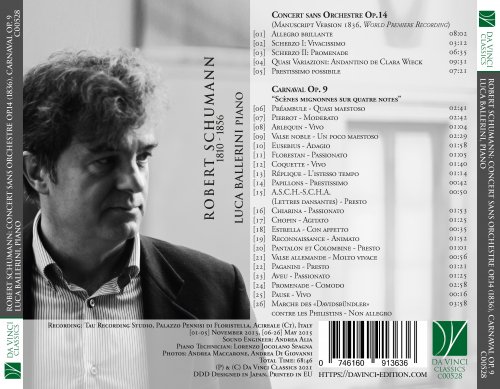

Luca Ballerini - Schumann: Concert sans Orchestre Op.14 (Manuscript Version 1836), Carnaval Op. 9 (2022)

BAND/ARTIST: Luca Ballerini

- Title: Schumann: Concert sans Orchestre Op.14 (Manuscript Version 1836), Carnaval Op. 9

- Year Of Release: 2022

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical Piano

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:08:46

- Total Size: 229 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Concert sans Orchestre in F Minor, Op. 14: I. Allegro brillante

02. Concert sans Orchestre in F Minor, Op. 14: II. Scherzo I: Vivacissimo

03. Concert sans Orchestre in F Minor, Op. 14: III. Scherzo II: Promenade

04. Concert sans Orchestre in F Minor, Op. 14: IV. Quasi Variazioni: Andantino de Clara Wieck

05. Concert sans Orchestre in F Minor, Op. 14: V. Prestissimo possibile

06. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 1 in A-Flat Major, Préambule-Quasi maestoso

07. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 2 in E-Flat Major, Pierrot-Moderato

08. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 3 in B-Flat Major, Arlequin-Vivo

09. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 4 in B-Flat Major, Valse noble-Un poco maestoso

10. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 5 in E-Flat Major, Eusebius-Adagio

11. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 6 in G Minor, Florestan-Passionato

12. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 7 in B-Flat Major, Coquette-Vivo

13. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 8 in B-Flat Major, Réplique-L'istesso tempo

14. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 9 in B-Flat Major, Papillons-Prestissimo

15. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 10 in E-Flat Major, A.S.C.H.-S.C.H.A. (Lettres dansantes)-Presto

16. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 11 in C Minor, Chiarina-Passionato

17. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 12 in A-Flat Major, Chopin-Agitato

18. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 13 in F Minor, Estrella-Con affetto

19. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 14 in A-Flat Major, Reconnaissance-Animato

20. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 15 in F Minor, Pantalon et Colombine-Presto

21. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 16 in A-Flat Major, Valse allemande-Molto vivace

22. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 17 in A-Flat Major, Paganini-Presto

23. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 18 in D-Flat Major, Aveu-Passionato

24. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 19 in A-Flat Major, Promenade-Comodo

25. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 20 in A-Flat Major, Pause-Vivo

26. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 21 in A-Flat Major, Marche des «Davidsbündler» contre les Philistins-Non allegro

Ludwig van Beethoven had brought the Sonata form to its highest point, but also fatally condemned it. Haydn had written more than fifty keyboard Sonatas; Beethoven wrote thirty-two; later composers rarely reached the number of ten Sonatas. More to the point, Beethoven had demonstrated the full potential of the dialectical opposition of the two main themes in the Sonata Allegro form; at the same time, he had pushed these oppositions to the extreme, so that later composers found it very challenging to equal his feats, or even to try.

This may be one of the reasons why Schumann’s Sonata op. 14 has such a complex story of continuing revisions, alterations, reworkings and restructuring, probably mirroring its composer’s perpetual quest for the (unachievable) perfect form.

This piece exists in two main versions, which are more frequently performed, but, during its composer’s lifetime, it took also other shapes. The two main versions are commonly referred to as Concert sans Orchestre (published in 1836) and Grande Sonate (printed in 1853). The first extant manuscript, puzzlingly dated “5th of June 1836”, already displays one of the stages of the composer’s afterthoughts. The work had originally been conceived as a Sonata in five movements, consisting of an “Allegro Brillante”, of a “Scherzo 1°. Vivacissimo”, of a “Scherzo 2°. Promenade”, of an “Intermezzo. Quasi Variazioni”, and of a “Prestissimo possible. Passionato”. A piano Sonata in five movements is certainly uncommon, and, in particular, the juxtaposition of two Scherzos in a row is unique. Interestingly, the second Scherzo is labelled “Promenade”, which, as we will shortly see, is a title Schumann evidently favoured. In spite of this, it was precisely this second Scherzo that would fall first under the axe of Schumann’s self-censorship.

The entire Sonata is woven around a red thread: red as love, one might romantically say. In fact, the theme which cyclically returns is indicated as Andantino de Clara Wieck, and was originally a musical idea by a teenage Clara Wieck. She was the gifted daughter of Robert’s piano teacher; before her tenth birthday, she had already demonstrated his talent both as a pianist and as a composer. Schumann had been deeply moved by his encounter with her, when he had arrived as a student of her father, and in spite of their pronounced difference in age. Although he had been briefly engaged to another damsel, Ernestine von Fricken (more on her later), by 1835 he had come to regard Clara once more as his soulmate, and possibly as his future wife. She was only sixteen at the time, and her father was by no means enthused by the possible liaison; as is well known, Clara and Robert would marry five years later, but only after having fought her father in court.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, young Robert’s mind was occupied by his betrothed, and her music filled his creative imagination. Thus, her theme recurs in varied forms throughout the Sonata’s fabric, even in the Finale in a version later discarded. Writing in 1838, Schumann referred to this Sonata when he told his beloved: “I wrote a concerto for you – and if this does not make clear my love for you, this one sole cry of the heart for you in which, incidentally, you did not even realise how many guises your theme assumed (forgive me, it is the composer speaking) – truly you have much to make up for and will have to love me even more in the future!”. A hint of the musical rivalry between the two members of the future couple is easily discernible here; moreover, it is questionable whether the young female composer was really flattered to see her theme so intensely reworked as to become unrecognizable in her own eyes… The diaries of the Schumann family, in the later years, would reveal many such situations, where the mutual devotion and love between the spouses was at times undermined by their professional relationship.

Already in 1836, however, letters between Schumann and his publisher Haslinger reveal that the Sonata was practically ready; in the same year, Schumann wrote to Ignaz Moscheles, to whom he would dedicate the Sonata, requesting his permission to do so.

A first considerable editing of the Sonata took place in spring 1836; at this stage, two of the original five movements were expunged from the work, which, by now, was called “Concerto” and had also lost two of the Variations on Clara’s theme. The version prior to this radical (and under certain viewpoints unjustified) editing has never been recorded until now; this Da Vinci Classics album, therefore, presents for the first time this work as Schumann had initially conceived it, thus demonstrating that, already in its earliest form, it stood as a perfectly balanced musical composition.

Receiving Schumann’s manuscript, the publisher shrewdly suggested to emphasise the idea that a Piano Concerto could be “without orchestra”, in spite of this being a contradiction in terms: a concerto may either be a certamen (a struggle) or a concentus (an ensemble playing), but in both cases the idea of a single musician playing seems to be ruled out. Still, one could “contend” with him- or herself, in the pursuit of perfect virtuosity. The work would once more revert to the title of Sonata at the time of its republication, in 1853, as a four-movements work. The Sonata’s dedicatee, Ignaz Moscheles, was impressed with it, although he did not fully appreciate it. He wrote that this Sonata/Concerto would encounter the approval of those “who are knowledgeable in the loftier language of the heroes of Art”, since, while not “fulfilling the requirements of a concerto”, it did possess “the characteristic attributes of a grand sonata”. The young composer evidently prized both lauds and criticism, and he published the dedicatee’s letter as an article in the review he had founded, adding: “So be it. Florestan and Euseb, make yourselves worthy of such a benevolent judgment by continuing in the future to be as demanding on yourselves as you are at times on others”.

But who are these Florestan and Eusebius? They are the pen names under which Schumann frequently wrote his articles, but also some of his musical pieces. Indeed, every single movement of Davidsbündlertänze op. 9 is signed by either “F.” or “E.”, and at times by both together. Davidsbündlertänze begins with a quote from another piece written by Clara Schumann, thus paying homage once more to his beloved. One might dare say that both “Florestan” and “Eusebius”, embodying Schumann’s two souls, were in love with Clara; just as Vult and Walt, the twin brothers who are the protagonists of Jean Paul Richter’s Flegeljahre, were both in love with young Wina. Flegeljahre had been one of Schumann’s favourite novels, and indeed can be said to have shaped substantially his worldview and artistic approach. His Papillons op. 2 are the musical transposition of several moments of the book; they close with an enchanted piece, where the Großvatertanz is heard while the bells strike midnight. The same theme of the Großvatertanz is also found as the closing piece of Carnaval op. 9, where another movement is also labelled Papillons, and where a quote from the first piece of op. 2 recurs in the piece called… “Florestan”.

Playing on the triple meaning of the German word Larve (mask, ghost, and larva), Schumann musically argued that we human beings always wear masks, hiding our true identities; they will be discarded as the pupa’s chrysalis when our true self will reveal itself as a butterfly (“papillon”).

Carnaval depicts various characters, as a carnival parade. Some of them are masks of the Commedia dell’arte: Arlequin, Pierrot, but also Pantalon et Colombine, etc. Others are real people with their true names, as is the case with Paganini (the protagonist of the most crazily virtuosic piece of the series) or Chopin, whose music is effectively parodied by his friend Schumann. Still other pieces portray types or characters, such as Coquette, the irresistible depiction of a vain girl. Others represent situations: Aveu, the timid avowal of a lover’s passion; Pause; Promenade, as in the discarded Scherzo of the Concerto sans Orchestre. Others are dances, such as the Valse noble or Valse allemande. Others make explicit the hidden programme of the entire series, whose subtitle is Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes. In fact, the melodic and harmonic material of Carnaval is derived largely from four notes, i.e. “A-S-C-H”. They spell out the name of Asch, a German city where Ernestine von Fricken lived. Schumann was evidently impressed by the fact that all four letters of that city’s name can be translated as musical notes (in various forms following the German musical alphabet), and also that they corresponded to the only musically translatable notes of his own family name (S-C-H-um-A-nn). Thus, Lettres dansantes represent the dizzying flight of these letters dancing together. Ernestine herself is present, though “masked”, in Carnaval: her piece is Estrella, and it is reported that, even after Schumann’s death, Clara would never play that piece in public. Still, she was there too, as Chiarina: the resemblance between Chiarina’s theme and that of the quote found as the opening gesture of Davidsbündlertänze is undeniable.

In the end, who are these Davidsbündler, and why does their March close Carnaval? “David’s companions” are the musical embodiment of the fellows who, together with the poet-king David, fought against the Philistines in the Bible. The Philistines of Schumann’s time were those opposed to true art, and to the innovations of the true artists; against them, the Companions (among whom were Florestan and Eusebius, but also Chopin, Paganini, Chiarina, Estrella and so on…) marched to the three-legged (i.e. dancing) pace of the Großvatertanz. And a triumphal march it was.

01. Concert sans Orchestre in F Minor, Op. 14: I. Allegro brillante

02. Concert sans Orchestre in F Minor, Op. 14: II. Scherzo I: Vivacissimo

03. Concert sans Orchestre in F Minor, Op. 14: III. Scherzo II: Promenade

04. Concert sans Orchestre in F Minor, Op. 14: IV. Quasi Variazioni: Andantino de Clara Wieck

05. Concert sans Orchestre in F Minor, Op. 14: V. Prestissimo possibile

06. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 1 in A-Flat Major, Préambule-Quasi maestoso

07. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 2 in E-Flat Major, Pierrot-Moderato

08. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 3 in B-Flat Major, Arlequin-Vivo

09. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 4 in B-Flat Major, Valse noble-Un poco maestoso

10. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 5 in E-Flat Major, Eusebius-Adagio

11. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 6 in G Minor, Florestan-Passionato

12. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 7 in B-Flat Major, Coquette-Vivo

13. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 8 in B-Flat Major, Réplique-L'istesso tempo

14. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 9 in B-Flat Major, Papillons-Prestissimo

15. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 10 in E-Flat Major, A.S.C.H.-S.C.H.A. (Lettres dansantes)-Presto

16. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 11 in C Minor, Chiarina-Passionato

17. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 12 in A-Flat Major, Chopin-Agitato

18. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 13 in F Minor, Estrella-Con affetto

19. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 14 in A-Flat Major, Reconnaissance-Animato

20. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 15 in F Minor, Pantalon et Colombine-Presto

21. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 16 in A-Flat Major, Valse allemande-Molto vivace

22. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 17 in A-Flat Major, Paganini-Presto

23. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 18 in D-Flat Major, Aveu-Passionato

24. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 19 in A-Flat Major, Promenade-Comodo

25. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 20 in A-Flat Major, Pause-Vivo

26. Carnaval, Op. 9 "Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes": No. 21 in A-Flat Major, Marche des «Davidsbündler» contre les Philistins-Non allegro

Ludwig van Beethoven had brought the Sonata form to its highest point, but also fatally condemned it. Haydn had written more than fifty keyboard Sonatas; Beethoven wrote thirty-two; later composers rarely reached the number of ten Sonatas. More to the point, Beethoven had demonstrated the full potential of the dialectical opposition of the two main themes in the Sonata Allegro form; at the same time, he had pushed these oppositions to the extreme, so that later composers found it very challenging to equal his feats, or even to try.

This may be one of the reasons why Schumann’s Sonata op. 14 has such a complex story of continuing revisions, alterations, reworkings and restructuring, probably mirroring its composer’s perpetual quest for the (unachievable) perfect form.

This piece exists in two main versions, which are more frequently performed, but, during its composer’s lifetime, it took also other shapes. The two main versions are commonly referred to as Concert sans Orchestre (published in 1836) and Grande Sonate (printed in 1853). The first extant manuscript, puzzlingly dated “5th of June 1836”, already displays one of the stages of the composer’s afterthoughts. The work had originally been conceived as a Sonata in five movements, consisting of an “Allegro Brillante”, of a “Scherzo 1°. Vivacissimo”, of a “Scherzo 2°. Promenade”, of an “Intermezzo. Quasi Variazioni”, and of a “Prestissimo possible. Passionato”. A piano Sonata in five movements is certainly uncommon, and, in particular, the juxtaposition of two Scherzos in a row is unique. Interestingly, the second Scherzo is labelled “Promenade”, which, as we will shortly see, is a title Schumann evidently favoured. In spite of this, it was precisely this second Scherzo that would fall first under the axe of Schumann’s self-censorship.

The entire Sonata is woven around a red thread: red as love, one might romantically say. In fact, the theme which cyclically returns is indicated as Andantino de Clara Wieck, and was originally a musical idea by a teenage Clara Wieck. She was the gifted daughter of Robert’s piano teacher; before her tenth birthday, she had already demonstrated his talent both as a pianist and as a composer. Schumann had been deeply moved by his encounter with her, when he had arrived as a student of her father, and in spite of their pronounced difference in age. Although he had been briefly engaged to another damsel, Ernestine von Fricken (more on her later), by 1835 he had come to regard Clara once more as his soulmate, and possibly as his future wife. She was only sixteen at the time, and her father was by no means enthused by the possible liaison; as is well known, Clara and Robert would marry five years later, but only after having fought her father in court.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, young Robert’s mind was occupied by his betrothed, and her music filled his creative imagination. Thus, her theme recurs in varied forms throughout the Sonata’s fabric, even in the Finale in a version later discarded. Writing in 1838, Schumann referred to this Sonata when he told his beloved: “I wrote a concerto for you – and if this does not make clear my love for you, this one sole cry of the heart for you in which, incidentally, you did not even realise how many guises your theme assumed (forgive me, it is the composer speaking) – truly you have much to make up for and will have to love me even more in the future!”. A hint of the musical rivalry between the two members of the future couple is easily discernible here; moreover, it is questionable whether the young female composer was really flattered to see her theme so intensely reworked as to become unrecognizable in her own eyes… The diaries of the Schumann family, in the later years, would reveal many such situations, where the mutual devotion and love between the spouses was at times undermined by their professional relationship.

Already in 1836, however, letters between Schumann and his publisher Haslinger reveal that the Sonata was practically ready; in the same year, Schumann wrote to Ignaz Moscheles, to whom he would dedicate the Sonata, requesting his permission to do so.

A first considerable editing of the Sonata took place in spring 1836; at this stage, two of the original five movements were expunged from the work, which, by now, was called “Concerto” and had also lost two of the Variations on Clara’s theme. The version prior to this radical (and under certain viewpoints unjustified) editing has never been recorded until now; this Da Vinci Classics album, therefore, presents for the first time this work as Schumann had initially conceived it, thus demonstrating that, already in its earliest form, it stood as a perfectly balanced musical composition.

Receiving Schumann’s manuscript, the publisher shrewdly suggested to emphasise the idea that a Piano Concerto could be “without orchestra”, in spite of this being a contradiction in terms: a concerto may either be a certamen (a struggle) or a concentus (an ensemble playing), but in both cases the idea of a single musician playing seems to be ruled out. Still, one could “contend” with him- or herself, in the pursuit of perfect virtuosity. The work would once more revert to the title of Sonata at the time of its republication, in 1853, as a four-movements work. The Sonata’s dedicatee, Ignaz Moscheles, was impressed with it, although he did not fully appreciate it. He wrote that this Sonata/Concerto would encounter the approval of those “who are knowledgeable in the loftier language of the heroes of Art”, since, while not “fulfilling the requirements of a concerto”, it did possess “the characteristic attributes of a grand sonata”. The young composer evidently prized both lauds and criticism, and he published the dedicatee’s letter as an article in the review he had founded, adding: “So be it. Florestan and Euseb, make yourselves worthy of such a benevolent judgment by continuing in the future to be as demanding on yourselves as you are at times on others”.

But who are these Florestan and Eusebius? They are the pen names under which Schumann frequently wrote his articles, but also some of his musical pieces. Indeed, every single movement of Davidsbündlertänze op. 9 is signed by either “F.” or “E.”, and at times by both together. Davidsbündlertänze begins with a quote from another piece written by Clara Schumann, thus paying homage once more to his beloved. One might dare say that both “Florestan” and “Eusebius”, embodying Schumann’s two souls, were in love with Clara; just as Vult and Walt, the twin brothers who are the protagonists of Jean Paul Richter’s Flegeljahre, were both in love with young Wina. Flegeljahre had been one of Schumann’s favourite novels, and indeed can be said to have shaped substantially his worldview and artistic approach. His Papillons op. 2 are the musical transposition of several moments of the book; they close with an enchanted piece, where the Großvatertanz is heard while the bells strike midnight. The same theme of the Großvatertanz is also found as the closing piece of Carnaval op. 9, where another movement is also labelled Papillons, and where a quote from the first piece of op. 2 recurs in the piece called… “Florestan”.

Playing on the triple meaning of the German word Larve (mask, ghost, and larva), Schumann musically argued that we human beings always wear masks, hiding our true identities; they will be discarded as the pupa’s chrysalis when our true self will reveal itself as a butterfly (“papillon”).

Carnaval depicts various characters, as a carnival parade. Some of them are masks of the Commedia dell’arte: Arlequin, Pierrot, but also Pantalon et Colombine, etc. Others are real people with their true names, as is the case with Paganini (the protagonist of the most crazily virtuosic piece of the series) or Chopin, whose music is effectively parodied by his friend Schumann. Still other pieces portray types or characters, such as Coquette, the irresistible depiction of a vain girl. Others represent situations: Aveu, the timid avowal of a lover’s passion; Pause; Promenade, as in the discarded Scherzo of the Concerto sans Orchestre. Others are dances, such as the Valse noble or Valse allemande. Others make explicit the hidden programme of the entire series, whose subtitle is Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes. In fact, the melodic and harmonic material of Carnaval is derived largely from four notes, i.e. “A-S-C-H”. They spell out the name of Asch, a German city where Ernestine von Fricken lived. Schumann was evidently impressed by the fact that all four letters of that city’s name can be translated as musical notes (in various forms following the German musical alphabet), and also that they corresponded to the only musically translatable notes of his own family name (S-C-H-um-A-nn). Thus, Lettres dansantes represent the dizzying flight of these letters dancing together. Ernestine herself is present, though “masked”, in Carnaval: her piece is Estrella, and it is reported that, even after Schumann’s death, Clara would never play that piece in public. Still, she was there too, as Chiarina: the resemblance between Chiarina’s theme and that of the quote found as the opening gesture of Davidsbündlertänze is undeniable.

In the end, who are these Davidsbündler, and why does their March close Carnaval? “David’s companions” are the musical embodiment of the fellows who, together with the poet-king David, fought against the Philistines in the Bible. The Philistines of Schumann’s time were those opposed to true art, and to the innovations of the true artists; against them, the Companions (among whom were Florestan and Eusebius, but also Chopin, Paganini, Chiarina, Estrella and so on…) marched to the three-legged (i.e. dancing) pace of the Großvatertanz. And a triumphal march it was.

Year 2022 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads