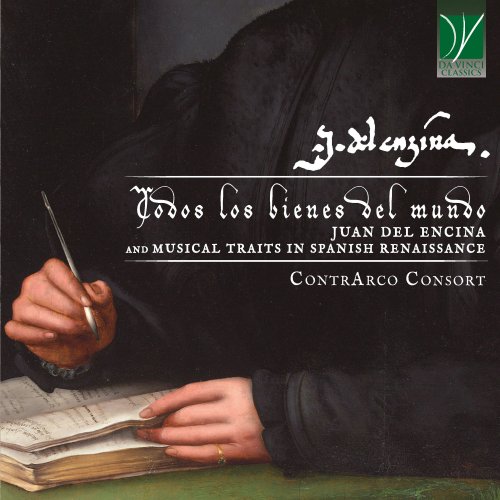

ContrArco Consort - Todos los bienes del mundo - Juan del Encina and Music Traits in Spanish Renaissance (2022)

BAND/ARTIST: ContrArco Consort

- Title: Todos los bienes del mundo - Juan del Encina and Music Traits in Spanish Renaissance

- Year Of Release: 2022

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 58:26 min

- Total Size: 298 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

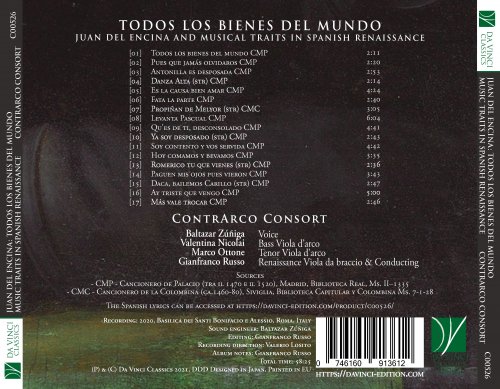

Tracklist:

1. Todos los bienes del mundo

2. Pues que jamás olvidaros

3. Antonilla es desposada

4. Danza Alta

5. Es la causa bien amar

6. Fata la parte

7. Propiñan de Melyor

8. Levanta Pascual

9. Qu'es de ti, desconsolado

10. Ya soy desposado

11. Soy contento y vos servida

12. Hoy comamos y bevamos

13. Romerico tu que vienes

14. Paguen mis ojos pues vieron

15. Daca, bailemos Carillo

16. Ay triste que vengo

17. Más vale trocar

Juan de Fermoselle, born in 1468 in Encina (Salamanca), place where he got his nickname “Encina” or “Enzina”, was playwright, composer, musician, poet and scholar in Spain across the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Century. He’s considered one of the founders of the Iberian Profane theatre; the medieval religious drama is thus transformed into the modern humanities instances; the celebration of love, glory and beauty are the new themes, described using popular jargon elevated to the highest literary and courtier rank. His production had been collected in the “Cancionero” of 1496, Cancionero de todas las obras de Juan del Enzina, published while he was at the court of the Dukes of Alba. It is the first book that collects compositions of a single author and uses the newly developed printing technology for its publishing circulation. This editorial experiment was highly successful if we look at the succeeding prints: 1501 (Seville), 1505 (Burgos), 1507 (Salamanca), 1509 (Salamanca), and 1516 (Zaragoza). In the preface Encina states that all the works present had been composed when he was between fourteen and twenty-five years of age, this may well be extended to his whole musical production. Even though the Cancionero of 1496 is exclusively literary, we can already find many of its works set to music in other songs books, such as the “Cancionero de Palacio” or the “Cancionero de Segovia”. This authentic “Opus Maius” of Encina offers a wide spectrum of the musical poetry of his period in Spain: we find religious and devotional compositions together with pieces of a moral or circumstantial nature (mournful, celebrative or farce pieces) and moreover love and satirical poetry. In this book we also find all the musical genres typical of the period: Villancicos, Canciones, and Romances. His works are always present in the Spanish cancioneros of that period, and just as it happens in the Cancionero de Palacio, they take the lion’s share, giving evidence that Encina was indeed the most popular composer in the Spain governed by the Catholic Kings. In the Cancionero de Palacio, drawn up between 1505 and 1520, we can find all the musical heritage of the salmantino: no less than sixty music compositions out of four hundred and fifty eight of the anthology, with three or four parts, are the ones signed by Encina although some researchers tend to assign him more pieces. The widespread liking of this composer while he was alive was probably due to his adherence to the musical style that, just like it happens in the italian Frottola, was in contrast with the complex austerity of Madrigal’s polyphony. He tended to privilege the highest voice, followed along with a simple counterpoint, often homorhythmic, and with scarce and short imitative episodes. We also can notice the use of the binary tempo, which contrasted the “ternary” philosophy of the music of the past, and the persistency of third-intervals in the harmony, apart from a few cadential arrivals. All these elements made our composer rather modern for its time. We can easily state that the salmantino’s production met wide taste of both common people and courtesans, thanks to its lyrical and musical comprehensibility. We can certainly find coherence as he was indeed quite fond to both the courtesan values and the popular ones. Certainly, peculiar in Encina’s work is the fusion of lyrics and rhythm where all the accents are in the right place and lyrics and sounds are totally fused among voices with a fluid metric movement and with careful choice of tone and sound lengths. Encina’s lyrics, specially love related themes, is certainly close to the rhetorical artifices of contemporary poetry; he overcomes this with his theatrical instinct, depicting is music with such an expressivity that will become fashion after over a century. Another element that makes him a rather modern composer for its time is the attention to emotions and state of mind and their musical rendering. This makes him different from the Flemish School composers, very present in the rest of Europe at the time. The melodic expressiveness, with its linear harmony, uses the modal structure to evoke narrative. All such variety merges in Juan del Encina, composer and poet of the highest level, able to give birth to compositions of equal beauty and depth. A good sample can be found in the romance ¿Qu’es de ti, desconsolado?, composed in 1492 to celebrate the conquest of Granada: we see that the lyrics celebrates enthusiastically the feat of the Reis Catolicos, Fernando and Isabella, talking directly to the defeated Boabdil, the last Moorish Sultan in Spain, but it is also characterized by a sad sympathy for the exiled beaten, hence the choice of a melancholy music in place of a fierce and triumphal one; this clearly shows a high sensibility , probably derived from the fact that Encina came from a conversos family. Let us not be tempted to interpret his ability to move the listener with an anachronistic need to express his own feelings, but certainly we have to appreciate his rhetorical ability in representing affections. Our idea to use voice and viols to render his work adheres to all these premises. Chant accompanied with instruments allows us to follow altogether the main melodic line and its lyrics even when counterpoint gets more intricated, and also marks expressively some sections. The choice for a consort of viols meets the starting homotimbric taste of that period and holds the polyphonic mixture as it’s written. Moreover, the use of bowed strings, makes a perfect choice as they are very close to the aesthetics and expressivity and imitation of human voice.

In his book “Il Libro del Cortegiano” (1528) Baldassarre Castiglione writes: “…Many kinds of music are found – he said – with both real voices and voices played by instruments, but I’m eager to know which might be the best, and when the courtesan ought to make use of it. – Nice Music – replied Messer Federico – is certainly singing with a good voice and with a nice taste; but even more singing with the viol, where all the sweetness can be discerned, and all the subtleties are heard as the ears are not occupied by multiple voices, and one is able to discover any mistake as well, something that doesn’t happen with choir singing where one helps the other. But more than anything I like “Recitar Cantando alla viola” so that singing and theatre are meld yielding incomparable beauty and cogency to the words, which is marvelous.

Also, all keyboard instruments are harmonious with their perfect consonances that fill our soul with musical sweetness. And equally delightful is the music with four viols, which is artful and sweet…”.

Our instruments are copies of viols found in paintings of contemporary artists: the Viola da Braccio comes from the Incoronazione della Vergine, ca.1510, by Raffaellino del Garbo (1466-1524), the tenor viol is one of the instruments seen in Madonna della Pace, c.1525, di Giacomo Francia (1486-1567), last but not least, the bass viol is a copy from the famous painting Estasi di Santa Cecilia, ca.1514, di Raffaello Sanzio (1483-1520). According to many scholars, it is precisely in this period that the viola da gamba, or viuhela de arco, developed in Spain, taking up the six-string tuning from the viuhela de mano, and no longer arm positions like the viella. Just as other composers, also Encina draws themes from the popular repertoire and from dance, as pointed out in his use of rhythm. In the villancico “Daca Bailemos Carillo”, which we offer in instrumental performance, the cadenced rhythm of the dance can be clearly seen. We have included two instrumental pieces in the program: an “Alta Danza” by Francisco de la Torre, present in the Cancionero de Palacio, and “Propiñan de Melyor” taken from the homogeneous repertoire of the Cancionero de la Colombina. Rhythm, in Encina works, often moves within the musical phrase, with close adherence to the text; this is apart from the tempo indication at the beginning of the piece being it, binary, ternary or quinary, as often found in the Spanish popular music and especially in the region of Salamanca. The way Encina playwriter uses music in his Eclogues, has suggested us an expressive and theatrical rendering in some villancicos. We aimed to bring forward his creative style, so different from other contemporary European poets and composers: more focused on the watermark and delicacy of counterpoint with its technical entanglements and even of a single note in relation to others and to a specific syllable and vocal, they often ended up forgetting the clarity of the lyrics. Juan del Encina lived in Rome where he got the musical appreciation of three popes and took his vows around 1518 although we don’t have any evidence of liturgical compositions. After a trip to Jerusalem, he was appointed Prior of the cathedral of Leon where he died in 1529.

In his book “Il Libro del Cortegiano” (1528) Baldassarre Castiglione writes: “…Many kinds of music are found – he said – with both real voices and voices played by instruments, but I’m eager to know which might be the best, and when the courtesan ought to make use of it. – Nice Music – replied Messer Federico – is certainly singing with a good voice and with a nice taste; but even more singing with the viol, where all the sweetness can be discerned, and all the subtleties are heard as the ears are not occupied by multiple voices, and one is able to discover any mistake as well, something that doesn’t happen with choir singing where one helps the other. But more than anything I like “Recitar Cantando alla viola” so that singing and theatre are meld yielding incomparable beauty and cogency to the words, which is marvelous.

Also, all keyboard instruments are harmonious with their perfect consonances that fill our soul with musical sweetness. And equally delightful is the music with four viols, which is artful and sweet…”.

Our instruments are copies of viols found in paintings of contemporary artists: the Viola da Braccio comes from the Incoronazione della Vergine, ca.1510, by Raffaellino del Garbo (1466-1524), the tenor viol is one of the instruments seen in Madonna della Pace, c.1525, di Giacomo Francia (1486-1567), last but not least, the bass viol is a copy from the famous painting Estasi di Santa Cecilia, ca.1514, di Raffaello Sanzio (1483-1520). According to many scholars, it is precisely in this period that the viola da gamba, or viuhela de arco, developed in Spain, taking up the six-string tuning from the viuhela de mano, and no longer arm positions like the viella. Just as other composers, also Encina draws themes from the popular repertoire and from dance, as pointed out in his use of rhythm. In the villancico “Daca Bailemos Carillo”, which we offer in instrumental performance, the cadenced rhythm of the dance can be clearly seen. We have included two instrumental pieces in the program: an “Alta Danza” by Francisco de la Torre, present in the Cancionero de Palacio, and “Propiñan de Melyor” taken from the homogeneous repertoire of the Cancionero de la Colombina. Rhythm, in Encina works, often moves within the musical phrase, with close adherence to the text; this is apart from the tempo indication at the beginning of the piece being it, binary, ternary or quinary, as often found in the Spanish popular music and especially in the region of Salamanca. The way Encina playwriter uses music in his Eclogues, has suggested us an expressive and theatrical rendering in some villancicos. We aimed to bring forward his creative style, so different from other contemporary European poets and composers: more focused on the watermark and delicacy of counterpoint with its technical entanglements and even of a single note in relation to others and to a specific syllable and vocal, they often ended up forgetting the clarity of the lyrics. Juan del Encina lived in Rome where he got the musical appreciation of three popes and took his vows around 1518 although we don’t have any evidence of liturgical compositions. After a trip to Jerusalem, he was appointed Prior of the cathedral of Leon where he died in 1529.

Year 2022 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads