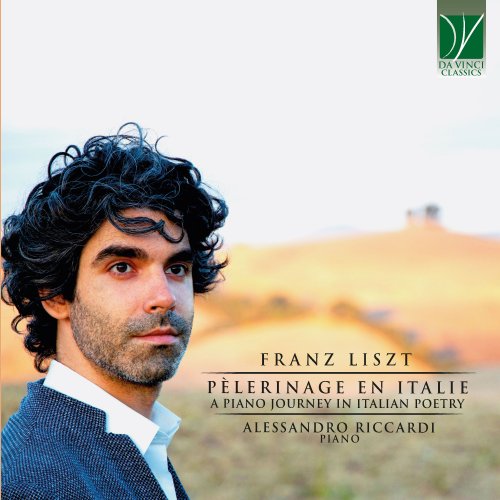

Alessandro Riccardi - Liszt: Pèlerinage en Italie (A Piano Journey in Italian Poetry) (2022)

BAND/ARTIST: Alessandro Riccardi

- Title: Liszt: Pèlerinage en Italie (A Piano Journey in Italian Poetry)

- Year Of Release: 2022

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 56:26

- Total Size: 198 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

01. Années de pèlerinage II, S. 161: No. 4, Sonetto 47 del Petrarca

02. Années de pèlerinage II, S. 161: No. 5, Sonetto 104 del Petrarca

03. Années de pèlerinage II, S. 161: No. 6, Sonetto 123 del Petrarca

04. Le Triomphe funèbre du Tasse, S. 517

05. Dante's Sonnett "Tanto gentile e tanto onesta", S. 479

06. Années de pèlerinage II, S. 161: No. 7, Après une lecture du Dante. Fantasia quasi Sonata

01. Années de pèlerinage II, S. 161: No. 4, Sonetto 47 del Petrarca

02. Années de pèlerinage II, S. 161: No. 5, Sonetto 104 del Petrarca

03. Années de pèlerinage II, S. 161: No. 6, Sonetto 123 del Petrarca

04. Le Triomphe funèbre du Tasse, S. 517

05. Dante's Sonnett "Tanto gentile e tanto onesta", S. 479

06. Années de pèlerinage II, S. 161: No. 7, Après une lecture du Dante. Fantasia quasi Sonata

The Middle Ages were an inexhaustible source of inspiration for visual artists, authors and musicians in the Romantic era. At times their veneration for the past transformed the real Middle Ages into a mythical period, fictionalizing the historical testimonies available at their epoch; at times, the Romantics reinterpreted the past by re-presenting it through the lens of their sensitivity.

If this attitude was common to many, if not all, the most important artists of the era, which Middle Ages they actually elected is a trait worth considering, and distinguishing some strands in the Romantic style. Inspiration could come from the archaic past of the Gaelic tradition, as happened with Mendelssohn and his fascination for the British islands, for their real or imagined bards, and for their lyrical vein. It could also come from Germanic tales and sagas, as would notoriously happen with Richard Wagner.

If, however, these two iconic artists looked north, or at least near home, other creators looked south; and this choice might also depend on religious aspects, since – in the nineteenth century – the northern countries of Western Europe evoked a Germanic heritage in which the sixteenth-century Reformations would take place, whilst the southern countries embodied the “unchanging” religious heritage of Catholicism.

Franz Liszt, in spite of his rather irregular life, was always deeply attracted by the Catholic faith, and it is therefore less surprising that he frequently took inspiration from the Latin Middle Ages when considering a model for his own creations. In particular, Dante and the other great Italian poets of the Trecento and Quattrocento – most notably Francesco Petrarca, or Petrarch, and Torquato Tasso – provided him with countless poetic stimuli which he often translated into new musical works.

Doubtlessly, Liszt’s stays in the Peninsula were not without effect in imbuing it with its culture and art. He lived on several occasion in Italy, but in particular the period 1837-9 was crucial for the creation of the second volume of his Années de pèlerinage. (Another fundamental stay would take place decades later, and result in such works as his Via Crucis). The second volume of Liszt’s collection of “pilgrimage years” follows the one dedicated to Switzerland, and portraying the fascinating landscape and nature of the Alpine country. In the “Italian” volume, Liszt mainly referred to Italian culture and poetry, with allusions to visual art (Raphael’s Sposalizio, the marriage of the Virgin Mary and St. Joseph), to literature and to music. The entire cycle was written between 1837 and 1849.

The three Sonnets by Petrarch are best described as songs without words. They had at first been conceived as real songs, with a tenor voice singing the immortal lines of Petrarch’s Canzoniere. However, it is in their form for solo piano that these pieces have reached and conquered immortality. The three Sonnets chosen by Liszt are drawn from those written as a homage to Laura’s life. Even if the immortal words of the Italian poet are silent in the version for solo piano, they still are integral to the musical pieces and crucial for their understanding. The composer cited the original Italian text by the corresponding musical works, and these faithfully mirror the emotions, feelings and rhetoric strategies of the verbal artwork.

The 47th Sonnet by Petrarch blesses everything connected with Laura: the day, month, year, season and time, hour and moment of their encounter, but also the places where they met, and even the sorrows of love, its wounds, sighs, tears and desire, together with the papers on which Petrarch writes those same lines, expressing his thought fixed on the beloved. This litany of blessings is echoed by Liszt’s music, which acquires an almost religious character; the delight one feels in love’s pangs, and the sorrow one experiences at the very heart of delight are rendered by carefully crafted contrasts and oppositions in the musical version. If the climax of sorrow is reached when the poem mentions the bow, arrows and grief piercing the lover’s heart, Laura’s smile and the very thought fixed on it are enough to console the artist.

The 104th Sonnet is one of the most iconic in the Canzoniere. Indeed, the sixteenth-century movement known as “Petrarchism”, and its epigones throughout the Baroque era would draw generously from Petrarch’s taste for oxymora. (Indeed, recent studies have found abundant traces of this trend even in as unlikely a context as the libretti of Bach’s church cantatas!). Here peace and war, fear and hope, burning and ice, flying and lying, blindness and sight, dumbness and crying, a desire for death and for life alike, hatred and love, sorrow and laughter: all of these opposites are found together. They are not reconciled – to the contrary: they maintain the full strength of their opposition. But poetry “harmonizes” them, and it is only appropriate that music should express this “harmony of opposites”. In this case, Liszt’s version is freer with respect to the original, and more conditioned by the composer’s virtuoso taste for extemporizing. Yet, the wealth of images provided by Petrarch offers countless opportunities to the musician’s fantasy, left free to portray a full palette of contrasting feelings.

The 123rd Sonnet describes Laura in even more idealized tones than was usual for the poet. She is transfigured into an angelic figure, and the dreamlike evocation of her person is more akin to dream or memory than to reality. This is beautifully rendered by Liszt in his own version, where all traces of heroic elan and vigorous declamation disappear. Indeed, this piano piece seems almost to anticipate the deliberate vagueness and timbral effects of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and constitutes one of the most innovative results of Liszt’s visionary poetry. Petrarch’s mention of a “dolce concerto”, a sweet concert, is appropriately rendered with exquisite tenderness by the composer.

From the same collection as the Petrarch Sonnets comes also the “Fantasia quasi Sonata” (the title deliberately misquotes Beethoven’s “Sonata quasi Fantasia”, as he labelled his two Sonatas op. 27). In this case, the poet who stimulated Liszt’s creativity was the other genius of the Italian Trecento, Dante Alighieri. (The production year of this Da Vinci Classics album coincides with the 700th anniversary of Dante’s death, and therefore the homage is very appropriate). “Après une lecture de Dante”, “after a Dante reading”: this piece is commonly referred to as “Dante Sonata” by many pianists. This indication also favours the creation of ideal parallels with the great B-minor Sonata, which similarly aims – albeit with different means – at evoking the greatest mysteries of human life and of the Christian faith.

The title bears also a further literary reference, in this case to Victor Hugo, who penned a collection titled Les voix intérieures – whose publication coincides with the first draft of Liszt’s work – and within which a poem by the same name as Liszt’s piece is found. Liszt’s piece underwent several rewritings, as was customary with him – particularly with the pieces he cherished most. In this case, the entire process took approximately two decades. Different from the other Lisztean masterpiece dedicated to Dante, the Dante Symphony, this piano piece seems to be only loosely connected to the Commedia, and, in particular, to evoke atmospheres and situations rather than specific characters or episodes. Certainly, here as in the “Petrarch” works, the great oppositions of human life (and afterlife!) are portrayed in full colours: from the anguished despair of hell to heavenly bliss, from pure hatred to the perfection of love. These oppositions were obviously resonant both with Romantic aesthetics and with Liszt’s own personality: the composer who penned one of the most thrilling representations of demonic forces (e.g. in his Mephisto Waltzes) was the same who dedicated thoughtful and sincere pages to the contemplation of Christ’s sorrows in his Via Crucis.

Dante is again the protagonist of one of the lesser-known transcriptions realized by Liszt. In this case, the original was a song, set to the Italian words of Dante’s poetry by Hans von Bülow, who was Liszt’s son-in-law. Bülow chose one of Dante’s most famous Sonnets, Tanto gentile e tanto onesta pare, in which the poet prizes the courtesy, elegance and grace of his beloved. Liszt’s version is less flashy and virtuosic than many other transcriptions he realized, and beautifully renders the refinedness of the song’s purity.

Liszt’s interest in the great poets may mirror his understanding of his own genius, and his ideal of romantic love seen also as a mystical experience. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that his Triomphe funèbre du Tasse has marked autobiographical traits. Just as Torquato Tasso had been misunderstood and despised by many during his lifetime, only to be admired and idolized after his death, the same – in Liszt’s mind – could also happen to him. This piece belongs in a set of three Funeral Odes, each existing in several versions; the “funereal triumph” portrayed here provides the composer with many creative stimuli resulting in a fascinating and densely chromatic work.

Together, the pieces recorded here offer a touching and emotional panorama on Liszt’s reception of Italian culture and literature, but also on his self-fashioning as a literary persona, in the style of the great poets of the past.

Chiara Bertoglio © 2021

If this attitude was common to many, if not all, the most important artists of the era, which Middle Ages they actually elected is a trait worth considering, and distinguishing some strands in the Romantic style. Inspiration could come from the archaic past of the Gaelic tradition, as happened with Mendelssohn and his fascination for the British islands, for their real or imagined bards, and for their lyrical vein. It could also come from Germanic tales and sagas, as would notoriously happen with Richard Wagner.

If, however, these two iconic artists looked north, or at least near home, other creators looked south; and this choice might also depend on religious aspects, since – in the nineteenth century – the northern countries of Western Europe evoked a Germanic heritage in which the sixteenth-century Reformations would take place, whilst the southern countries embodied the “unchanging” religious heritage of Catholicism.

Franz Liszt, in spite of his rather irregular life, was always deeply attracted by the Catholic faith, and it is therefore less surprising that he frequently took inspiration from the Latin Middle Ages when considering a model for his own creations. In particular, Dante and the other great Italian poets of the Trecento and Quattrocento – most notably Francesco Petrarca, or Petrarch, and Torquato Tasso – provided him with countless poetic stimuli which he often translated into new musical works.

Doubtlessly, Liszt’s stays in the Peninsula were not without effect in imbuing it with its culture and art. He lived on several occasion in Italy, but in particular the period 1837-9 was crucial for the creation of the second volume of his Années de pèlerinage. (Another fundamental stay would take place decades later, and result in such works as his Via Crucis). The second volume of Liszt’s collection of “pilgrimage years” follows the one dedicated to Switzerland, and portraying the fascinating landscape and nature of the Alpine country. In the “Italian” volume, Liszt mainly referred to Italian culture and poetry, with allusions to visual art (Raphael’s Sposalizio, the marriage of the Virgin Mary and St. Joseph), to literature and to music. The entire cycle was written between 1837 and 1849.

The three Sonnets by Petrarch are best described as songs without words. They had at first been conceived as real songs, with a tenor voice singing the immortal lines of Petrarch’s Canzoniere. However, it is in their form for solo piano that these pieces have reached and conquered immortality. The three Sonnets chosen by Liszt are drawn from those written as a homage to Laura’s life. Even if the immortal words of the Italian poet are silent in the version for solo piano, they still are integral to the musical pieces and crucial for their understanding. The composer cited the original Italian text by the corresponding musical works, and these faithfully mirror the emotions, feelings and rhetoric strategies of the verbal artwork.

The 47th Sonnet by Petrarch blesses everything connected with Laura: the day, month, year, season and time, hour and moment of their encounter, but also the places where they met, and even the sorrows of love, its wounds, sighs, tears and desire, together with the papers on which Petrarch writes those same lines, expressing his thought fixed on the beloved. This litany of blessings is echoed by Liszt’s music, which acquires an almost religious character; the delight one feels in love’s pangs, and the sorrow one experiences at the very heart of delight are rendered by carefully crafted contrasts and oppositions in the musical version. If the climax of sorrow is reached when the poem mentions the bow, arrows and grief piercing the lover’s heart, Laura’s smile and the very thought fixed on it are enough to console the artist.

The 104th Sonnet is one of the most iconic in the Canzoniere. Indeed, the sixteenth-century movement known as “Petrarchism”, and its epigones throughout the Baroque era would draw generously from Petrarch’s taste for oxymora. (Indeed, recent studies have found abundant traces of this trend even in as unlikely a context as the libretti of Bach’s church cantatas!). Here peace and war, fear and hope, burning and ice, flying and lying, blindness and sight, dumbness and crying, a desire for death and for life alike, hatred and love, sorrow and laughter: all of these opposites are found together. They are not reconciled – to the contrary: they maintain the full strength of their opposition. But poetry “harmonizes” them, and it is only appropriate that music should express this “harmony of opposites”. In this case, Liszt’s version is freer with respect to the original, and more conditioned by the composer’s virtuoso taste for extemporizing. Yet, the wealth of images provided by Petrarch offers countless opportunities to the musician’s fantasy, left free to portray a full palette of contrasting feelings.

The 123rd Sonnet describes Laura in even more idealized tones than was usual for the poet. She is transfigured into an angelic figure, and the dreamlike evocation of her person is more akin to dream or memory than to reality. This is beautifully rendered by Liszt in his own version, where all traces of heroic elan and vigorous declamation disappear. Indeed, this piano piece seems almost to anticipate the deliberate vagueness and timbral effects of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and constitutes one of the most innovative results of Liszt’s visionary poetry. Petrarch’s mention of a “dolce concerto”, a sweet concert, is appropriately rendered with exquisite tenderness by the composer.

From the same collection as the Petrarch Sonnets comes also the “Fantasia quasi Sonata” (the title deliberately misquotes Beethoven’s “Sonata quasi Fantasia”, as he labelled his two Sonatas op. 27). In this case, the poet who stimulated Liszt’s creativity was the other genius of the Italian Trecento, Dante Alighieri. (The production year of this Da Vinci Classics album coincides with the 700th anniversary of Dante’s death, and therefore the homage is very appropriate). “Après une lecture de Dante”, “after a Dante reading”: this piece is commonly referred to as “Dante Sonata” by many pianists. This indication also favours the creation of ideal parallels with the great B-minor Sonata, which similarly aims – albeit with different means – at evoking the greatest mysteries of human life and of the Christian faith.

The title bears also a further literary reference, in this case to Victor Hugo, who penned a collection titled Les voix intérieures – whose publication coincides with the first draft of Liszt’s work – and within which a poem by the same name as Liszt’s piece is found. Liszt’s piece underwent several rewritings, as was customary with him – particularly with the pieces he cherished most. In this case, the entire process took approximately two decades. Different from the other Lisztean masterpiece dedicated to Dante, the Dante Symphony, this piano piece seems to be only loosely connected to the Commedia, and, in particular, to evoke atmospheres and situations rather than specific characters or episodes. Certainly, here as in the “Petrarch” works, the great oppositions of human life (and afterlife!) are portrayed in full colours: from the anguished despair of hell to heavenly bliss, from pure hatred to the perfection of love. These oppositions were obviously resonant both with Romantic aesthetics and with Liszt’s own personality: the composer who penned one of the most thrilling representations of demonic forces (e.g. in his Mephisto Waltzes) was the same who dedicated thoughtful and sincere pages to the contemplation of Christ’s sorrows in his Via Crucis.

Dante is again the protagonist of one of the lesser-known transcriptions realized by Liszt. In this case, the original was a song, set to the Italian words of Dante’s poetry by Hans von Bülow, who was Liszt’s son-in-law. Bülow chose one of Dante’s most famous Sonnets, Tanto gentile e tanto onesta pare, in which the poet prizes the courtesy, elegance and grace of his beloved. Liszt’s version is less flashy and virtuosic than many other transcriptions he realized, and beautifully renders the refinedness of the song’s purity.

Liszt’s interest in the great poets may mirror his understanding of his own genius, and his ideal of romantic love seen also as a mystical experience. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that his Triomphe funèbre du Tasse has marked autobiographical traits. Just as Torquato Tasso had been misunderstood and despised by many during his lifetime, only to be admired and idolized after his death, the same – in Liszt’s mind – could also happen to him. This piece belongs in a set of three Funeral Odes, each existing in several versions; the “funereal triumph” portrayed here provides the composer with many creative stimuli resulting in a fascinating and densely chromatic work.

Together, the pieces recorded here offer a touching and emotional panorama on Liszt’s reception of Italian culture and literature, but also on his self-fashioning as a literary persona, in the style of the great poets of the past.

Chiara Bertoglio © 2021

Year 2022 | Classical | FLAC / APE

Facebook

Twitter

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads