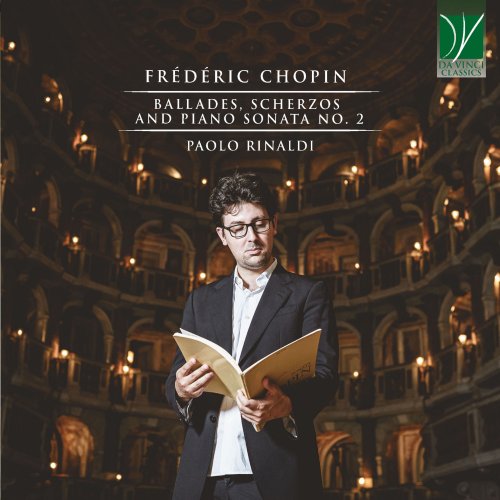

Paolo Rinaldi - Frédéric Chopin: Ballades, Scherzos and Piano Sonata No. 2 (2022)

BAND/ARTIST: Paolo Rinaldi

- Title: Frédéric Chopin: Ballades, Scherzos and Piano Sonata No. 2

- Year Of Release: 2022

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical Piano

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 00:59:08

- Total Size: 232 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Ballade No. 3 in A-Flat Major, Op. 47

02. Ballade No. 4 in F Minor, Op. 52

03. Scherzo No. 3 in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 39

04. Scherzo No. 2 in B-Flat Minor, Op. 31

05. Piano Sonata No. 2 in B-Flat Minor, Op. 35 "Funeral March": I. Grave-Doppio Movimento

06. Piano Sonata No. 2 in B-Flat Minor, Op. 35 "Funeral March": II. Scherzo

07. Piano Sonata No. 2 in B-Flat Minor, Op. 35 "Funeral March": III. Marche funèbre

08. Piano Sonata No. 2 in B-Flat Minor, Op. 35 "Funeral March": IV. Finale, presto

This Da Vinci Classics album comprises some of the most famous and beloved masterpieces not only among Chopin’s works, but also in the entire piano literature. True, piano literature without Chopin is hardly imaginable; but Chopin without his Ballades, his Scherzos and his Sonatas would not be Chopin.

The programme is composed by four shorter works, each conceived individually while also being one in a set of four similar pieces, and by one larger creation, in the most important form created in Western music, i.e. that of the Sonata.

Chopin was the first to apply the name of “Ballade” to a musical work; he would not be the last, however. Following in his footsteps, and doubtlessly influenced by him, two musicians standing on different and opposing sides of the Romantic aesthetics would continue the tradition; and, after Franz Liszt and Johannes Brahms, countless other epigones would adhere and pay homage to the idea inaugurated by Chopin.

Prior to him, the “ballade” was a literary genre, rooted in the Middle Ages, and characterized by the poetical intonation of a narrative, frequently interspersed by both romantic love and adventure. Of course, the Romantic era was particularly interested in the Middle Ages, and also in the intertwining of music and literature. One has only to think of E. T. A. Hoffmann’s works, or of Wackenroder, or of Jean Paul, to say nothing of Robert Schumann, and an impression of how these two art forms were interrelated immediately emerges.

Indeed, we owe precisely to Robert Schumann a hint which has caused the spilling of much ink. In an article on the review he had founded, the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, and written the day after an in-person encounter with Chopin, Schumann affirmed that his friend’s Ballades were inspired by the eponymous literary works by Adam Mickiewicz. The famous Polish poet lived in Paris as Chopin did, and the two had befriended each other; Mickiewicz had created Romantic ballades capable of evoking the distant past of the Middle Ages while infusing it with the new Romantic spirit.

The idea of a musical narrative would have dramatically appealed to Schumann, who was a professional writer himself and some of whose most iconic works had been inspired by literary masterpieces – by Jean Paul and by E. T. A. Hoffmann in particular. However, in spite of their contemporaneity and of their friendship, Chopin and Schumann were very different from each other, and literary inspiration was certainly much less relevant for the Polish musician than for the German – and, possibly, not relevant at all.

Musicians and performers of the following two centuries have debated about whether Chopin’s Ballades do actually correspond to Mickiewicz’s, and, if so, which corresponds to which. I will not take a stance in this debate, but merely cite the most widespread identifications. Certainly, however, Chopin’s musical creation are exquisitely musical, and even if a remote inspiration could have come to him from literary works, their value lies far beyond the narratives they may or may not encompass.

The Third Ballade, op. 47 in A-flat major, was composed by Chopin in the summer of 1841. It was first mentioned by Chopin in a letter to his publisher Fontana a few months later. The work had probably been written while Chopin was in Nohant, at a time of great creative fecundity (another of his absolute masterpieces, the Fantasy op. 49, dates also from the same period). In this case, the possible literary inspiration has been identified with a poem called Świtezianka, or Undine, representing the enchanted world of water spirits. True or not, certainly this Ballade displays different features from most of its sisters; it is more serene, lighter, more transparent and luminous. Regardless of its connection with a particular literary work, this Ballade is a “real” Ballade inasmuch as it shares with its sisters and with the genre created by Chopin a “narrativity” surpassing the possible detailed correspondence with a poem. This piece possesses a magnificent melodic breadth, and is sustained throughout its various episodes by an unfailing singing tone, even in the brilliancy and light-heartedness of the second theme.

The following Ballade, the Fourth, came to light shortly after. It was finished by December 15th, 1842, when Chopin offered it to the German publisher Breitkopf & Härtel; the piece would see the light in the following year. This Ballade is dedicated to “Madame la Baronne Nathaniel de Rothschild”, and, in this case, the likely Mickiewicz inspiration might be his poem The Three Budrys. It recounts the tale of three brothers sent by their father in seek of adventure, and who find love instead. This Ballade is perhaps the most complex – besides being the longest – of the four. Formally, it combines a modified Sonata form with variations. The piece’s opening is unforgettable, and it contradicts the piece’s key and the related atmosphere. The bell-like murmured repeated notes seem to suggest rather than to narrate; yet, in the continuation of the piece, a robust narrative is established, also by means of the numerous and unexpected modulations. Corresponding to tonal variety, Chopin also employs a great number of techniques and of dynamic shades, thus building a rich and varied landscape within the space of a dozen minutes approximately.

Relative brevity characterizes also Chopin’s four Scherzos. In this case, the name used by Chopin was not new: the Italian word for jest or joke had been popularized as a musical term by Ludwig van Beethoven, who frequently replaced the usual Minuets in his four-movement Sonatas by Scherzos. However, the capricious and humorous style of a “jest” is retained in Beethoven’s movements by this name, whilst those by Chopin are hardly ironic. As Schumann put it, when reviewing the first Scherzo, “How will gravity array itself, if wit is already cloaked so darkly?”.

The second Scherzo was written and published in 1837, with a dedication to Countess Adèle Fürtenstein. Once more, Schumann was drawn to literary comparisons – this time without even the hint of a reference by the composer himself – and liked to juxtapose this piece to Byron’s poems, “so overflowing with tenderness, boldness, love and contempt”. This Scherzo in fact is permeated by the full palette of emotions and feelings; in particular, the exquisite tenderness of the Trio contrasts markedly with the fiery outbursts of the B-flat minor episodes.

The third Scherzo dates from the following year, 1839, and was composed during Chopin’s disastrous vacation with George Sand in Majorca, at the Monastery of Valldemossa. It is dedicated to a pupil of the composer, Adolphe Gutmann. Perhaps as a homage to his gifted student, it is interspersed with technical difficulties, although always in the service of a deep musicality. For example, its octave passages have become legendary in piano literature, but what is most remarkable is the tightness of its musical narrative. In spite of the gloomy mood Chopin had throughout his stay in Majorca, this Scherzo is lighter in tone than the two preceding ones, and is also remarkable for its daring use of harmony with audacious combinations which seem to anticipate Wagner’s music.

The final piece on this CD is the superb B-flat minor Sonata, no. 2 op. 35. Its composition took place at about the same time as the two Scherzos recorded here, while Chopin was in Nohant. At the Sonata’s heart is found the Marche funèbre, whose composition precedes that of the other movements by two years (it was written already in 1837). The Sonata elicited contrasting opinions among Chopin’s contemporaries, and even those who were usually enthused by Chopin’s genius had some perplexities. Schumann disliked the Marche funèbre, whilst Mendelssohn loved it – but found the following Finale as being entirely out of place. After nearly two centuries, however, this Sonata has revealed itself to be the absolute masterpiece we now know. The robust coherence of the work and its internal cogency are probably to be ascribed precisely to the conditions of its composition: the Sonata was plotted and conceived around the Marche funèbre. Death is protagonist, here as it was – allegedly in Chopin’s words – in the second Scherzo. The Finale that disconcerted Mendelssohn has been likened to a sweeping wind in a cemetery; and even though Chopin tended to dismiss this imaginative interpretation, doubtlessly it represents a reaction to the mystery of death so solemnly embodied in the Funeral March, clearly reminiscent of Beethoven’s op. 26. Anxiety and anguish are found throughout the work, with its galloping passages, its breathtaking paces, the islands of respite without real peace. The abundant use of the diminished seventh, a true icon of suffering and pain in Classical music, becomes almost a leitmotiv, punctuating this beautiful composition with references to grief.

These five works, therefore, beautifully testify to Chopin’s mature style, with the multifaceted moods he lived and transmitted with his music, and with the innovative technique he had crafted. They display his full mastery of form, his unequalled melodic vein, and also his capability to rigorously sustain prolonged narratives, capturing his hearers with the full power of his creative genius.

01. Ballade No. 3 in A-Flat Major, Op. 47

02. Ballade No. 4 in F Minor, Op. 52

03. Scherzo No. 3 in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 39

04. Scherzo No. 2 in B-Flat Minor, Op. 31

05. Piano Sonata No. 2 in B-Flat Minor, Op. 35 "Funeral March": I. Grave-Doppio Movimento

06. Piano Sonata No. 2 in B-Flat Minor, Op. 35 "Funeral March": II. Scherzo

07. Piano Sonata No. 2 in B-Flat Minor, Op. 35 "Funeral March": III. Marche funèbre

08. Piano Sonata No. 2 in B-Flat Minor, Op. 35 "Funeral March": IV. Finale, presto

This Da Vinci Classics album comprises some of the most famous and beloved masterpieces not only among Chopin’s works, but also in the entire piano literature. True, piano literature without Chopin is hardly imaginable; but Chopin without his Ballades, his Scherzos and his Sonatas would not be Chopin.

The programme is composed by four shorter works, each conceived individually while also being one in a set of four similar pieces, and by one larger creation, in the most important form created in Western music, i.e. that of the Sonata.

Chopin was the first to apply the name of “Ballade” to a musical work; he would not be the last, however. Following in his footsteps, and doubtlessly influenced by him, two musicians standing on different and opposing sides of the Romantic aesthetics would continue the tradition; and, after Franz Liszt and Johannes Brahms, countless other epigones would adhere and pay homage to the idea inaugurated by Chopin.

Prior to him, the “ballade” was a literary genre, rooted in the Middle Ages, and characterized by the poetical intonation of a narrative, frequently interspersed by both romantic love and adventure. Of course, the Romantic era was particularly interested in the Middle Ages, and also in the intertwining of music and literature. One has only to think of E. T. A. Hoffmann’s works, or of Wackenroder, or of Jean Paul, to say nothing of Robert Schumann, and an impression of how these two art forms were interrelated immediately emerges.

Indeed, we owe precisely to Robert Schumann a hint which has caused the spilling of much ink. In an article on the review he had founded, the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, and written the day after an in-person encounter with Chopin, Schumann affirmed that his friend’s Ballades were inspired by the eponymous literary works by Adam Mickiewicz. The famous Polish poet lived in Paris as Chopin did, and the two had befriended each other; Mickiewicz had created Romantic ballades capable of evoking the distant past of the Middle Ages while infusing it with the new Romantic spirit.

The idea of a musical narrative would have dramatically appealed to Schumann, who was a professional writer himself and some of whose most iconic works had been inspired by literary masterpieces – by Jean Paul and by E. T. A. Hoffmann in particular. However, in spite of their contemporaneity and of their friendship, Chopin and Schumann were very different from each other, and literary inspiration was certainly much less relevant for the Polish musician than for the German – and, possibly, not relevant at all.

Musicians and performers of the following two centuries have debated about whether Chopin’s Ballades do actually correspond to Mickiewicz’s, and, if so, which corresponds to which. I will not take a stance in this debate, but merely cite the most widespread identifications. Certainly, however, Chopin’s musical creation are exquisitely musical, and even if a remote inspiration could have come to him from literary works, their value lies far beyond the narratives they may or may not encompass.

The Third Ballade, op. 47 in A-flat major, was composed by Chopin in the summer of 1841. It was first mentioned by Chopin in a letter to his publisher Fontana a few months later. The work had probably been written while Chopin was in Nohant, at a time of great creative fecundity (another of his absolute masterpieces, the Fantasy op. 49, dates also from the same period). In this case, the possible literary inspiration has been identified with a poem called Świtezianka, or Undine, representing the enchanted world of water spirits. True or not, certainly this Ballade displays different features from most of its sisters; it is more serene, lighter, more transparent and luminous. Regardless of its connection with a particular literary work, this Ballade is a “real” Ballade inasmuch as it shares with its sisters and with the genre created by Chopin a “narrativity” surpassing the possible detailed correspondence with a poem. This piece possesses a magnificent melodic breadth, and is sustained throughout its various episodes by an unfailing singing tone, even in the brilliancy and light-heartedness of the second theme.

The following Ballade, the Fourth, came to light shortly after. It was finished by December 15th, 1842, when Chopin offered it to the German publisher Breitkopf & Härtel; the piece would see the light in the following year. This Ballade is dedicated to “Madame la Baronne Nathaniel de Rothschild”, and, in this case, the likely Mickiewicz inspiration might be his poem The Three Budrys. It recounts the tale of three brothers sent by their father in seek of adventure, and who find love instead. This Ballade is perhaps the most complex – besides being the longest – of the four. Formally, it combines a modified Sonata form with variations. The piece’s opening is unforgettable, and it contradicts the piece’s key and the related atmosphere. The bell-like murmured repeated notes seem to suggest rather than to narrate; yet, in the continuation of the piece, a robust narrative is established, also by means of the numerous and unexpected modulations. Corresponding to tonal variety, Chopin also employs a great number of techniques and of dynamic shades, thus building a rich and varied landscape within the space of a dozen minutes approximately.

Relative brevity characterizes also Chopin’s four Scherzos. In this case, the name used by Chopin was not new: the Italian word for jest or joke had been popularized as a musical term by Ludwig van Beethoven, who frequently replaced the usual Minuets in his four-movement Sonatas by Scherzos. However, the capricious and humorous style of a “jest” is retained in Beethoven’s movements by this name, whilst those by Chopin are hardly ironic. As Schumann put it, when reviewing the first Scherzo, “How will gravity array itself, if wit is already cloaked so darkly?”.

The second Scherzo was written and published in 1837, with a dedication to Countess Adèle Fürtenstein. Once more, Schumann was drawn to literary comparisons – this time without even the hint of a reference by the composer himself – and liked to juxtapose this piece to Byron’s poems, “so overflowing with tenderness, boldness, love and contempt”. This Scherzo in fact is permeated by the full palette of emotions and feelings; in particular, the exquisite tenderness of the Trio contrasts markedly with the fiery outbursts of the B-flat minor episodes.

The third Scherzo dates from the following year, 1839, and was composed during Chopin’s disastrous vacation with George Sand in Majorca, at the Monastery of Valldemossa. It is dedicated to a pupil of the composer, Adolphe Gutmann. Perhaps as a homage to his gifted student, it is interspersed with technical difficulties, although always in the service of a deep musicality. For example, its octave passages have become legendary in piano literature, but what is most remarkable is the tightness of its musical narrative. In spite of the gloomy mood Chopin had throughout his stay in Majorca, this Scherzo is lighter in tone than the two preceding ones, and is also remarkable for its daring use of harmony with audacious combinations which seem to anticipate Wagner’s music.

The final piece on this CD is the superb B-flat minor Sonata, no. 2 op. 35. Its composition took place at about the same time as the two Scherzos recorded here, while Chopin was in Nohant. At the Sonata’s heart is found the Marche funèbre, whose composition precedes that of the other movements by two years (it was written already in 1837). The Sonata elicited contrasting opinions among Chopin’s contemporaries, and even those who were usually enthused by Chopin’s genius had some perplexities. Schumann disliked the Marche funèbre, whilst Mendelssohn loved it – but found the following Finale as being entirely out of place. After nearly two centuries, however, this Sonata has revealed itself to be the absolute masterpiece we now know. The robust coherence of the work and its internal cogency are probably to be ascribed precisely to the conditions of its composition: the Sonata was plotted and conceived around the Marche funèbre. Death is protagonist, here as it was – allegedly in Chopin’s words – in the second Scherzo. The Finale that disconcerted Mendelssohn has been likened to a sweeping wind in a cemetery; and even though Chopin tended to dismiss this imaginative interpretation, doubtlessly it represents a reaction to the mystery of death so solemnly embodied in the Funeral March, clearly reminiscent of Beethoven’s op. 26. Anxiety and anguish are found throughout the work, with its galloping passages, its breathtaking paces, the islands of respite without real peace. The abundant use of the diminished seventh, a true icon of suffering and pain in Classical music, becomes almost a leitmotiv, punctuating this beautiful composition with references to grief.

These five works, therefore, beautifully testify to Chopin’s mature style, with the multifaceted moods he lived and transmitted with his music, and with the innovative technique he had crafted. They display his full mastery of form, his unequalled melodic vein, and also his capability to rigorously sustain prolonged narratives, capturing his hearers with the full power of his creative genius.

Year 2022 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads