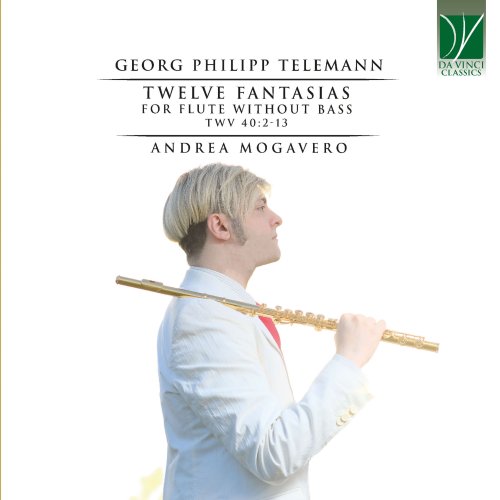

Andrea Mogavero - Georg Philipp Telemann: Twelve Fantasias For Flute Without Bass TWV 40:2-13 (2022)

BAND/ARTIST: Andrea Mogavero

- Title: Georg Philipp Telemann: Twelve Fantasias For Flute Without Bass TWV 40:2-13

- Year Of Release: 2022

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 00:50:21

- Total Size: 233 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:2: No. 1 in A Major

02. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:3: No. 2 in A Minor

03. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:4: No. 3 in B Minor

04. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:5: No. 4 in B-Flat Major

05. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:6: No. 5 in C Major

06. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:7: No. 6 in D Minor

07. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:8: No. 7 in D Major

08. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:9: No. 8 in E Minor

09. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:10: No. 9 in E Major

10. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:11: No. 10 in F-Sharp Minor

11. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:12: No. 11 in G Major

12. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:13: No. 12 in G Minor

When one thinks of the most iconic German musician of the Baroque era, the obvious name that comes to mind is that of Johann Sebastian Bach. During their lifetimes, however, Bach was decidedly less famous and appreciated than his contemporary Georg Philipp Telemann. Whilst Bach had been almost predestined to the musician’s career, as he was but one of the numerous musicians of his family (to the point that “Bach” had become a synonymous for “musician”), Telemann had had another path traced for him. He was encouraged to study law, and at first did obey his family’s orders. Soon, however, it became clear that nothing except music could satisfy his genius and his talent.

And if one thinks of a composer who wrote an astonishing quantity of music, once again the name that comes to mind is that of Bach. Here, however, and different from judgements of artistic quality, a direct comparison is possible, and Telemann outweighs his famous contemporary by many lengths. One has merely to consider that Bach probably wrote four Passions (only two of which, alas, survive), whilst Telemann wrote fifty examples of this genre. This proportion is respected in virtually all genres, and the complete works by Telemann are an impressive collection.

True, Bach could not devote the entirety of his time to composition (as he probably would have wished), since teaching duties, performances, and the business of his extra-large family occupied much time and energy. Still, Telemann in turn did not compose full time. He spent a noteworthy part of his free time in the activity of learning to play a high number of instruments. His accomplishments as a poly-instrumentalist led him to master virtually all of the principal performance techniques on the instruments of his era; therefore, his writing is very idiomatic for all instruments, and demonstrates his impressive skill both as a performer and as a creator.

At Telemann’s time, the transverse flute did not have a very extensive repertoire, in spite of being the direct descendant of one of the oldest instruments of humankind. The role it would acquire had been firmly held, up to the early eighteenth century, by the recorder, by far the favourite wind instrument employed by many musicians of the Renaissance and Early Baroque era.

The transverse flute’s ascent resulted from the joint efforts of three categories together: composers who demonstrated their interest in this particular instrument and explored its possibilities both as a member of the orchestra and as a solo instrument; performers who developed, transmitted, taught and experimented with new playing techniques; instrument makers who developed many subtle innovations which favoured both expressivity and virtuosity on this instrument.

On many occasions, exploiting the newly-found popularity of this instrument, composers (and publishers) tended to add the transverse flute as an option for the performance of violin works. In terms of range, of course, the two instruments are similar, and one vocation they have in common is that to the intonation of long melodic lines. However, and beyond the obvious timbral difference, the violin has a wider lower range, and can play double-stops and chords which are impossible on the Baroque transverse flute.

It is therefore slightly surprising that the title-page of the original edition of Telemann’s Fantasias bears the title of Fantasie per il Violino, senza Basso, and even omits the composer’s name. It is handwritten on the only surviving copy of this collection, which is currently in the holdings of the collections of the Bibliothèque Royale in Brussels, Belgium. Whilst the absence of the composer’s name and the seeming destination for the violin would normally undermine the attempts to attribute it to another instrumental destination, in this case there is unanimous consensus concerning the identification of the series. It evidently corresponds to the “12 Fantaisies à Travers. sans Basse” which are found both in a Catalogue of Telemann’s works issued in Amsterdam in 1733 and in a listing of his works reported by Johann Mattheson seven years later.

The survival of this copy was fundamental, as it enables us to know, perform and enjoy one of the absolute masterpieces in the flute literature. A dozen is always a good number, and many collections of musical works in the era were arranged by groups of twelve, or at times six (as Bach’s Soli for violin and for cello), or at times twenty-four (as in Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier). The citation of Bach’s works is not yet another attempt to speak of Bach when discussing Telemann. Rather, it is useful because it allows us to compare collections which display undeniable similarities along with important differences. As was the case with Bach’s Soli, instruments normally employed for the performance of melodies (as violins, cellos and flutes), and which usually needed an “accompaniment” when performing the role of a soloist, were called to stand alone on the musical stage, and to acquire self-sufficiency. This was perhaps easiest in the case of the cello, whose range exceeds that of the other two instruments, and which possesses both low and high notes. Moreover, Bach was able to create polyphonic textures (including Fugues!) for these seemingly “monodic” instrument, through the careful use of double-stops and chords, and also by exploiting aural illusions. Just as the human eye can reconstruct a shape when given only a few of its landmarks, similarly the ear can “complete” a polyphonic texture by sustaining, in its imagination, the notes which cannot be actually held and sustained by the performer.

This technique is also abundantly found in Telemann’s Fantasias, and is used with immense skill and a typically Baroque taste for the surprising, the unusual and the bizarre.

Similar to the Well-Tempered Clavier, moreover, Telemann’s Fantasias are organized by key, although with different principles and results, as we will shortly see.

At about the time of their creation, the “Fantasia” was defined as follows by J. G. Walther, who authored a famous Dictionary of Music (Musikalische Lexicon, 1732): “a Fantasia is the expression of a person with good taste who plays after his own invention, without paying too much attention to certain limitations of the tactus”. In other words, Fantasias represent the outpouring of one’s sentiments and feelings, with the intensity typical for the Baroque era, but also with their systematic codification in the Theory of the Affections. These expressions were not haphazard or unruly statements of spontaneous feelings; rather, they united the Baroque affirmation of the individual’s standing and viewpoint (Descartes’ moi qui pense) with the incoming rationalism of the Enlightenment. The human being as the measure of the universe is represented in its freedom from rhythmic constraints: these Fantasias possess a dimension of capriciousness, fancy and liberty which always fascinates performers and listeners alike. However, they are also carefully crafted masterpieces, demonstrating their composer’s mastery of flute technique and his inexhaustible inventiveness as a source of musical ideas.

The composer’s care in the creation of this collection is evident from many details: in all likelihood, he also did the engraving for the printing plates (as he liked to do with his most important works). Moreover, the pieces are ordered by their key, in an almost perfect ascending scale. Different from the Well-Tempered Clavier, however, the keys whose performance was particularly arduous – or almost impossible – on the transverse flute are avoided.

Within the collection, elegant patterns can also be recognized: for example, as happens with Bach’s Goldberg Variationen and with the other volumes of his Clavier-Übung, the first movement of the collection’s second half is a French overture, thus marking a new beginning with the solemnity which is normally associated to this genre. Another pattern is that constituted by four triplets of Fantasias with regular modal patterns: employing “M” for the major mode and “m” for the minor mode, we have the scheme: Mmm, MMm, MmM, mMm.

Together, the twelve compositions embody a variety of musical styles and genres, as were fashionable in the Baroque era. Many examples of dance rhythms and patterns are found throughout the series, including allemandes, courantes, bourrées, gavottes, minuets, polonaises and gigues.

Constant variety is also provided by the skillful use of the registers, which frequently suggest an imaginary dialogue of several instruments, and by the fanciful use of rests, at times suspending the musical discourse with gestures suggesting both wit and mystery. The virtuosity reached by Telemann in his “polyphonic” treatment of the flute is evident already in the first Fantasia, with its fugato sections. Other Fantasias explore the world of the Church Sonata, thus freeing the transverse flute from the constraints of the Arcadian setting. Among the Fantasias’ many movements, Telemann manages to find room for virtually all moods and styles: from the solemnity of the French Overture to the chromaticism of the eighth Fantasia, from the sweetness of the sixth to the virtuosity of the eleventh, with its concerto-like style, to name but few. Together, therefore, these Fantasias display the full palette of the transverse flute’s potential, and the immense creative powers of their creator.

01. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:2: No. 1 in A Major

02. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:3: No. 2 in A Minor

03. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:4: No. 3 in B Minor

04. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:5: No. 4 in B-Flat Major

05. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:6: No. 5 in C Major

06. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:7: No. 6 in D Minor

07. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:8: No. 7 in D Major

08. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:9: No. 8 in E Minor

09. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:10: No. 9 in E Major

10. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:11: No. 10 in F-Sharp Minor

11. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:12: No. 11 in G Major

12. Twelve Fantasias for Flute without Bass, TWV 40:13: No. 12 in G Minor

When one thinks of the most iconic German musician of the Baroque era, the obvious name that comes to mind is that of Johann Sebastian Bach. During their lifetimes, however, Bach was decidedly less famous and appreciated than his contemporary Georg Philipp Telemann. Whilst Bach had been almost predestined to the musician’s career, as he was but one of the numerous musicians of his family (to the point that “Bach” had become a synonymous for “musician”), Telemann had had another path traced for him. He was encouraged to study law, and at first did obey his family’s orders. Soon, however, it became clear that nothing except music could satisfy his genius and his talent.

And if one thinks of a composer who wrote an astonishing quantity of music, once again the name that comes to mind is that of Bach. Here, however, and different from judgements of artistic quality, a direct comparison is possible, and Telemann outweighs his famous contemporary by many lengths. One has merely to consider that Bach probably wrote four Passions (only two of which, alas, survive), whilst Telemann wrote fifty examples of this genre. This proportion is respected in virtually all genres, and the complete works by Telemann are an impressive collection.

True, Bach could not devote the entirety of his time to composition (as he probably would have wished), since teaching duties, performances, and the business of his extra-large family occupied much time and energy. Still, Telemann in turn did not compose full time. He spent a noteworthy part of his free time in the activity of learning to play a high number of instruments. His accomplishments as a poly-instrumentalist led him to master virtually all of the principal performance techniques on the instruments of his era; therefore, his writing is very idiomatic for all instruments, and demonstrates his impressive skill both as a performer and as a creator.

At Telemann’s time, the transverse flute did not have a very extensive repertoire, in spite of being the direct descendant of one of the oldest instruments of humankind. The role it would acquire had been firmly held, up to the early eighteenth century, by the recorder, by far the favourite wind instrument employed by many musicians of the Renaissance and Early Baroque era.

The transverse flute’s ascent resulted from the joint efforts of three categories together: composers who demonstrated their interest in this particular instrument and explored its possibilities both as a member of the orchestra and as a solo instrument; performers who developed, transmitted, taught and experimented with new playing techniques; instrument makers who developed many subtle innovations which favoured both expressivity and virtuosity on this instrument.

On many occasions, exploiting the newly-found popularity of this instrument, composers (and publishers) tended to add the transverse flute as an option for the performance of violin works. In terms of range, of course, the two instruments are similar, and one vocation they have in common is that to the intonation of long melodic lines. However, and beyond the obvious timbral difference, the violin has a wider lower range, and can play double-stops and chords which are impossible on the Baroque transverse flute.

It is therefore slightly surprising that the title-page of the original edition of Telemann’s Fantasias bears the title of Fantasie per il Violino, senza Basso, and even omits the composer’s name. It is handwritten on the only surviving copy of this collection, which is currently in the holdings of the collections of the Bibliothèque Royale in Brussels, Belgium. Whilst the absence of the composer’s name and the seeming destination for the violin would normally undermine the attempts to attribute it to another instrumental destination, in this case there is unanimous consensus concerning the identification of the series. It evidently corresponds to the “12 Fantaisies à Travers. sans Basse” which are found both in a Catalogue of Telemann’s works issued in Amsterdam in 1733 and in a listing of his works reported by Johann Mattheson seven years later.

The survival of this copy was fundamental, as it enables us to know, perform and enjoy one of the absolute masterpieces in the flute literature. A dozen is always a good number, and many collections of musical works in the era were arranged by groups of twelve, or at times six (as Bach’s Soli for violin and for cello), or at times twenty-four (as in Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier). The citation of Bach’s works is not yet another attempt to speak of Bach when discussing Telemann. Rather, it is useful because it allows us to compare collections which display undeniable similarities along with important differences. As was the case with Bach’s Soli, instruments normally employed for the performance of melodies (as violins, cellos and flutes), and which usually needed an “accompaniment” when performing the role of a soloist, were called to stand alone on the musical stage, and to acquire self-sufficiency. This was perhaps easiest in the case of the cello, whose range exceeds that of the other two instruments, and which possesses both low and high notes. Moreover, Bach was able to create polyphonic textures (including Fugues!) for these seemingly “monodic” instrument, through the careful use of double-stops and chords, and also by exploiting aural illusions. Just as the human eye can reconstruct a shape when given only a few of its landmarks, similarly the ear can “complete” a polyphonic texture by sustaining, in its imagination, the notes which cannot be actually held and sustained by the performer.

This technique is also abundantly found in Telemann’s Fantasias, and is used with immense skill and a typically Baroque taste for the surprising, the unusual and the bizarre.

Similar to the Well-Tempered Clavier, moreover, Telemann’s Fantasias are organized by key, although with different principles and results, as we will shortly see.

At about the time of their creation, the “Fantasia” was defined as follows by J. G. Walther, who authored a famous Dictionary of Music (Musikalische Lexicon, 1732): “a Fantasia is the expression of a person with good taste who plays after his own invention, without paying too much attention to certain limitations of the tactus”. In other words, Fantasias represent the outpouring of one’s sentiments and feelings, with the intensity typical for the Baroque era, but also with their systematic codification in the Theory of the Affections. These expressions were not haphazard or unruly statements of spontaneous feelings; rather, they united the Baroque affirmation of the individual’s standing and viewpoint (Descartes’ moi qui pense) with the incoming rationalism of the Enlightenment. The human being as the measure of the universe is represented in its freedom from rhythmic constraints: these Fantasias possess a dimension of capriciousness, fancy and liberty which always fascinates performers and listeners alike. However, they are also carefully crafted masterpieces, demonstrating their composer’s mastery of flute technique and his inexhaustible inventiveness as a source of musical ideas.

The composer’s care in the creation of this collection is evident from many details: in all likelihood, he also did the engraving for the printing plates (as he liked to do with his most important works). Moreover, the pieces are ordered by their key, in an almost perfect ascending scale. Different from the Well-Tempered Clavier, however, the keys whose performance was particularly arduous – or almost impossible – on the transverse flute are avoided.

Within the collection, elegant patterns can also be recognized: for example, as happens with Bach’s Goldberg Variationen and with the other volumes of his Clavier-Übung, the first movement of the collection’s second half is a French overture, thus marking a new beginning with the solemnity which is normally associated to this genre. Another pattern is that constituted by four triplets of Fantasias with regular modal patterns: employing “M” for the major mode and “m” for the minor mode, we have the scheme: Mmm, MMm, MmM, mMm.

Together, the twelve compositions embody a variety of musical styles and genres, as were fashionable in the Baroque era. Many examples of dance rhythms and patterns are found throughout the series, including allemandes, courantes, bourrées, gavottes, minuets, polonaises and gigues.

Constant variety is also provided by the skillful use of the registers, which frequently suggest an imaginary dialogue of several instruments, and by the fanciful use of rests, at times suspending the musical discourse with gestures suggesting both wit and mystery. The virtuosity reached by Telemann in his “polyphonic” treatment of the flute is evident already in the first Fantasia, with its fugato sections. Other Fantasias explore the world of the Church Sonata, thus freeing the transverse flute from the constraints of the Arcadian setting. Among the Fantasias’ many movements, Telemann manages to find room for virtually all moods and styles: from the solemnity of the French Overture to the chromaticism of the eighth Fantasia, from the sweetness of the sixth to the virtuosity of the eleventh, with its concerto-like style, to name but few. Together, therefore, these Fantasias display the full palette of the transverse flute’s potential, and the immense creative powers of their creator.

Year 2022 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads