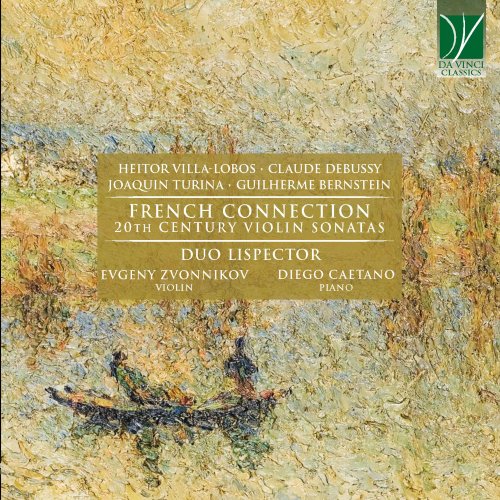

Evgeny Zvonnikov, Diego Caetano, Duo Lispector - Heitor Villa-Lobos, Claude Debussy, Joaquin Turina, Guilherme Bernstein: French Connection (20th Century Violin Sonatas) (2021)

BAND/ARTIST: Evgeny Zvonnikov, Diego Caetano, Duo Lispector

- Title: Heitor Villa-Lobos, Claude Debussy, Joaquin Turina, Guilherme Bernstein: French Connection (20th Century Violin Sonatas)

- Year Of Release: 2021

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

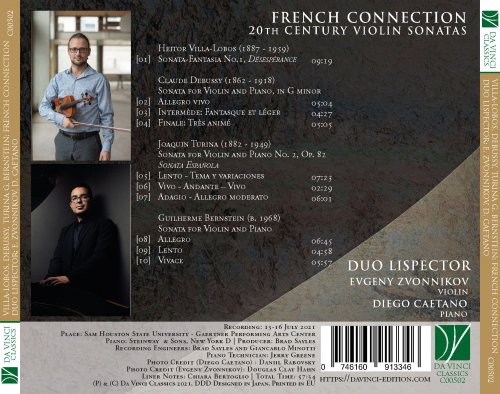

- Total Time: 00:57:34

- Total Size: 270 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Sonata fantasia No.1, Op. 35 "Désespérance"

02. Sonate pour violon et piano in G Minor, L. 140: I. Allegro vivo

03. Sonate pour violon et piano in G Minor, L. 140: II. Intermède. Fantasque et léger

04. Sonate pour violon et piano in G Minor, L. 140: III. Finale. Très animé

05. Violin Sonata No.2, Op. 82: I. Lento - Tema y variaciones

06. Violin Sonata No.2, Op. 82: II. Vivo - Andante - Vivo

07. Violin Sonata No.2, Op. 82: III. Adagio - Allegro moderato

08. Sonata for Violin and Piano: I. Allegro

09. Sonata for Violin and Piano: II. Lento

10. Sonata for Violin and Piano: III. Vivace

The repertoire for violin and piano is among the richest in the panorama of classical chamber music. History of this repertoire dates back to the origins of the piano in the eighteenth century with its features evolving in parallel with instrumental modifications and aesthetic taste.

Early examples of this repertoire were conceived “for piano with violin accompaniment”: the violin part being clearly subordinated to the piano. In many cases, these early Sonatas could also be played without violin. While there exists Sonatas by Mozart conditioned by this approach, his mature works in this genre are among the first masterpieces for the violin and piano repertoire. Since then, virtually no major composer has failed to dedicate at least one work to this ensemble.

The twentieth century experienced a crisis of the Sonata form, as it was considered too strictly bound to tonal rules, too often employed by Romantic composers, and too rigid and predetermined. Still, despite these critical opinions, important composers of the twentieth century accepted the challenge of such an august genre and contributed their share to its magnificent repertoire.

Among the gems of the Violin Sonata repertoire were two masterpieces by composers from the French-speaking area, Gabriel Fauré and César Franck. Their Sonatas explored new itineraries, in particular the timbral aspects of the violin and piano duo which paved the way for twentieth-century innovations. If the Classical-Romantic tradition of the German-speaking countries had established the genre and contributed a harvest of masterpieces, the Franco-Belgian composers were able to lead this genre into the twentieth century.

The four Sonatas recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album represent interesting fruits of the modern repertoire of violin and piano Sonatas. The pieces beautifully intertwine and illuminate new possibilities for this ensemble and musical form. Moreover, three of them revolve around French culture and reveal the influences of the early French school.

Only one of the composers represented in this album was a Frenchman. However, both the Brazilian musician Heitor Villa-Lobos and the Spaniard Joaquín Turina viewed Paris as their source of inspiration. Paradoxically, the “French” Sonata by Claude Debussy is interspersed with reference to the folkloric musical traditions of other countries (despite the Sonata’s explicit connection to French country and culture), while the Brazilian and the Spanish composers had to struggle with their fascination with France before weaving the traditions of their country into the fabric of their classical compositions.

Among the composers recorded here, Claude Debussy was the eldest. Most of his life took place in the nineteenth century. Interestingly, he neglected the violin and piano duo until the very last years of his life. As recalled by his publisher, Jacques Durand, “After his famous String Quartet, Debussy had not written any more chamber music. Then, at the Concerts Durand, he heard again the Septet with trumpet by Saint-Saëns and his sympathy for this means of musical expression was reawakened. He admitted the fact to me, and I warmly encouraged him to follow his inclination. And that is how the idea of the six sonatas for various instruments came about.”

It was then, Debussy sketched the project for a group of six Sonatas for various chamber music ensembles. He was interested in exploring both usual and unusual timbral combinations, intending for his last Sonata to gather all the instruments employed in the preceding five.

Troubled by the violence of World War I plaguing France and ill with cancer, Debussy completed only three of the projected six Sonatas. Debussy’s illness was painful, and the war had destroyed the beautiful and nonchalant world of the previous decades. The first of the sonatas was the Cello and Piano Sonata; the second was scored for a very unusual ensemble, flute, viola and harp (or piano). The third, and last, was the Sonata for Violin and Piano.

All three Sonatas are brief and compact. The extreme distillation of the musical language, which Debussy had always practiced, became a true need for the ailing composer. Written in 1917, the Sonata recorded here can be considered as Debussy’s swan song. It was the last work he performed in public, when he premiered it with violinist Gaston Poulet on May 5th, 1917.

Shortly before the premiere, Debussy voiced his satisfaction with his composition. Yet, one month after the concert, dismissed the work in self-deprecatory terms, “You should know, my too trusting friend, that I only wrote this Sonata to get rid of the thing, spurred on as I was by my dear publisher. You, who are able to read between the staves, will see traces of [Poe’s] The Imp of the Perverse, who encourages one to choose the very subject which should be ignored. This Sonata will be interesting from a documentary viewpoint and as an example of what may be produced by a sick man in time of war”.

This piece can be considered as Debussy’s last masterwork, despite his characterization as interesting from a “documentary viewpoint.” The first movement is quintessential Debussy, with its refined quest for infinitesimal sound nuances, and with its intimate intensity. Without indulging in sentimentality, a trait Debussy abhorred, his movement touches the listener deeply precisely due to its seeming restraint and expressive power.

The second movement, Intermède, gives the impression of a spontaneous improvisation, and its overall mood is of a dreamy dialogue, at times interrupted by outbursts of energetic rhythms.

Similar to Franck’s use in the majestic Violin Sonata, a suggestion of a cyclic form resurfaces in the connection between first and last movement. Here, the overall mood is serene, even joyful, with dance rhythms and sensuous passages. It is as if music had brought a smile on the composer’s countenance, despite his personal pain and that of his country. In fact, the projected cycle of six Sonatas had an explicit “French” connotation, affirmed in the homage to the great French composers of the seventeenth and eighteenth century, and highlighted by Debussy’s choice to appear on the title page as “French composer”. During the difficult times of a World War, Debussy understood that beauty and culture were the strongest weapons, and the only ones which could bring healing and hope. Yet, his love for his country was not “nationalistic” in a narrow sense, as is revealed by his use of Iberian and “gipsy” suggestions throughout the composition.

In the previous years, Debussy had been among the role models of a young Joaquín Turina. Like many other musicians, Turina had been attracted to the sparkling musical life of the French capital city. Born in Seville, Andalusia, Turina arrived in Paris in 1905 where he studied at the Schola Cantorum. The influence of Vincent d’Indy provided him with compositional wisdom dating back to d’Indy’s own teacher, César Franck. If the Schola Cantorum represented the bulwark of classical tradition, Turina was equally fascinated by the linguistic experiments of a “progressive” composer, as was Claude Debussy.

However, upon hearing the premiere of Turina’s Piano Quintet op. 1 in Paris, the Spanish composers Manuel de Falla and Isaac Albéniz advised him to abandon the French style he adopted, and to look with interest and participation to the musical heritage of his homeland. That advice proved fundamental for the young composer, who would later become one of the main representatives of a Spanish style in classical music. The Second Violin Sonata op. 82, recorded here, is named Sonata Española. Written in 1934, it mirrors the inquietudes of the years immediately preceding the Spanish Civil War. The first movement references the Spanish tradition of musical variations, a practice typical of Spanish music already in the sixteenth century. One of the Variations evokes the musical heritage of the Basque region, characterized by rhythms in quintuple metre, a zortziko.

Similar to Turina, Villa-Lobos would become among the most successful “classical” composers who expressed the heritage of Brazil in music. However, virtually no trace of Brazilian folklore is found in his First Violin Sonata, which has indeed a distinctly French flavor. Villa-Lobos crossed the ocean to undertake musical studies in France, but only after the composition of this Sonata. Still, its melancholy mood (corresponding to its title “Despair”) is clearly allusive to fin-de-siècle French music.

Another fin-de-siècle (in this case, the end of the twentieth century) is represented by the most recent work of this CD, the Sonata para violino e piano. Written in 1995, by Brazilian composer Guilherme Bernstein in his late twenties, opens on an incisive motto, presented at the unison by the violin and piano. The first movement sees the dialectics between a lyrical Cantabile espressivo in tempo rubato and contrasting sections with a powerful rhythmical drive. Leitmotifs are disseminated throughout the score, which appears as tightly knitted. The second movement expands the initial motivic cells, embracing very small intervals, and broadens them to reach expressive climaxes enhanced by rhythmical tensions. The third movement is a virtuosic, galloping perpetuum mobile built on a ceaseless and breathtaking succession of semiquavers.

Together, these four works portray the inexhaustible potential of the Violin and Piano Sonata and underpin the inspiration it has created — and continues to create — on the greatest composers of all times.

01. Sonata fantasia No.1, Op. 35 "Désespérance"

02. Sonate pour violon et piano in G Minor, L. 140: I. Allegro vivo

03. Sonate pour violon et piano in G Minor, L. 140: II. Intermède. Fantasque et léger

04. Sonate pour violon et piano in G Minor, L. 140: III. Finale. Très animé

05. Violin Sonata No.2, Op. 82: I. Lento - Tema y variaciones

06. Violin Sonata No.2, Op. 82: II. Vivo - Andante - Vivo

07. Violin Sonata No.2, Op. 82: III. Adagio - Allegro moderato

08. Sonata for Violin and Piano: I. Allegro

09. Sonata for Violin and Piano: II. Lento

10. Sonata for Violin and Piano: III. Vivace

The repertoire for violin and piano is among the richest in the panorama of classical chamber music. History of this repertoire dates back to the origins of the piano in the eighteenth century with its features evolving in parallel with instrumental modifications and aesthetic taste.

Early examples of this repertoire were conceived “for piano with violin accompaniment”: the violin part being clearly subordinated to the piano. In many cases, these early Sonatas could also be played without violin. While there exists Sonatas by Mozart conditioned by this approach, his mature works in this genre are among the first masterpieces for the violin and piano repertoire. Since then, virtually no major composer has failed to dedicate at least one work to this ensemble.

The twentieth century experienced a crisis of the Sonata form, as it was considered too strictly bound to tonal rules, too often employed by Romantic composers, and too rigid and predetermined. Still, despite these critical opinions, important composers of the twentieth century accepted the challenge of such an august genre and contributed their share to its magnificent repertoire.

Among the gems of the Violin Sonata repertoire were two masterpieces by composers from the French-speaking area, Gabriel Fauré and César Franck. Their Sonatas explored new itineraries, in particular the timbral aspects of the violin and piano duo which paved the way for twentieth-century innovations. If the Classical-Romantic tradition of the German-speaking countries had established the genre and contributed a harvest of masterpieces, the Franco-Belgian composers were able to lead this genre into the twentieth century.

The four Sonatas recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album represent interesting fruits of the modern repertoire of violin and piano Sonatas. The pieces beautifully intertwine and illuminate new possibilities for this ensemble and musical form. Moreover, three of them revolve around French culture and reveal the influences of the early French school.

Only one of the composers represented in this album was a Frenchman. However, both the Brazilian musician Heitor Villa-Lobos and the Spaniard Joaquín Turina viewed Paris as their source of inspiration. Paradoxically, the “French” Sonata by Claude Debussy is interspersed with reference to the folkloric musical traditions of other countries (despite the Sonata’s explicit connection to French country and culture), while the Brazilian and the Spanish composers had to struggle with their fascination with France before weaving the traditions of their country into the fabric of their classical compositions.

Among the composers recorded here, Claude Debussy was the eldest. Most of his life took place in the nineteenth century. Interestingly, he neglected the violin and piano duo until the very last years of his life. As recalled by his publisher, Jacques Durand, “After his famous String Quartet, Debussy had not written any more chamber music. Then, at the Concerts Durand, he heard again the Septet with trumpet by Saint-Saëns and his sympathy for this means of musical expression was reawakened. He admitted the fact to me, and I warmly encouraged him to follow his inclination. And that is how the idea of the six sonatas for various instruments came about.”

It was then, Debussy sketched the project for a group of six Sonatas for various chamber music ensembles. He was interested in exploring both usual and unusual timbral combinations, intending for his last Sonata to gather all the instruments employed in the preceding five.

Troubled by the violence of World War I plaguing France and ill with cancer, Debussy completed only three of the projected six Sonatas. Debussy’s illness was painful, and the war had destroyed the beautiful and nonchalant world of the previous decades. The first of the sonatas was the Cello and Piano Sonata; the second was scored for a very unusual ensemble, flute, viola and harp (or piano). The third, and last, was the Sonata for Violin and Piano.

All three Sonatas are brief and compact. The extreme distillation of the musical language, which Debussy had always practiced, became a true need for the ailing composer. Written in 1917, the Sonata recorded here can be considered as Debussy’s swan song. It was the last work he performed in public, when he premiered it with violinist Gaston Poulet on May 5th, 1917.

Shortly before the premiere, Debussy voiced his satisfaction with his composition. Yet, one month after the concert, dismissed the work in self-deprecatory terms, “You should know, my too trusting friend, that I only wrote this Sonata to get rid of the thing, spurred on as I was by my dear publisher. You, who are able to read between the staves, will see traces of [Poe’s] The Imp of the Perverse, who encourages one to choose the very subject which should be ignored. This Sonata will be interesting from a documentary viewpoint and as an example of what may be produced by a sick man in time of war”.

This piece can be considered as Debussy’s last masterwork, despite his characterization as interesting from a “documentary viewpoint.” The first movement is quintessential Debussy, with its refined quest for infinitesimal sound nuances, and with its intimate intensity. Without indulging in sentimentality, a trait Debussy abhorred, his movement touches the listener deeply precisely due to its seeming restraint and expressive power.

The second movement, Intermède, gives the impression of a spontaneous improvisation, and its overall mood is of a dreamy dialogue, at times interrupted by outbursts of energetic rhythms.

Similar to Franck’s use in the majestic Violin Sonata, a suggestion of a cyclic form resurfaces in the connection between first and last movement. Here, the overall mood is serene, even joyful, with dance rhythms and sensuous passages. It is as if music had brought a smile on the composer’s countenance, despite his personal pain and that of his country. In fact, the projected cycle of six Sonatas had an explicit “French” connotation, affirmed in the homage to the great French composers of the seventeenth and eighteenth century, and highlighted by Debussy’s choice to appear on the title page as “French composer”. During the difficult times of a World War, Debussy understood that beauty and culture were the strongest weapons, and the only ones which could bring healing and hope. Yet, his love for his country was not “nationalistic” in a narrow sense, as is revealed by his use of Iberian and “gipsy” suggestions throughout the composition.

In the previous years, Debussy had been among the role models of a young Joaquín Turina. Like many other musicians, Turina had been attracted to the sparkling musical life of the French capital city. Born in Seville, Andalusia, Turina arrived in Paris in 1905 where he studied at the Schola Cantorum. The influence of Vincent d’Indy provided him with compositional wisdom dating back to d’Indy’s own teacher, César Franck. If the Schola Cantorum represented the bulwark of classical tradition, Turina was equally fascinated by the linguistic experiments of a “progressive” composer, as was Claude Debussy.

However, upon hearing the premiere of Turina’s Piano Quintet op. 1 in Paris, the Spanish composers Manuel de Falla and Isaac Albéniz advised him to abandon the French style he adopted, and to look with interest and participation to the musical heritage of his homeland. That advice proved fundamental for the young composer, who would later become one of the main representatives of a Spanish style in classical music. The Second Violin Sonata op. 82, recorded here, is named Sonata Española. Written in 1934, it mirrors the inquietudes of the years immediately preceding the Spanish Civil War. The first movement references the Spanish tradition of musical variations, a practice typical of Spanish music already in the sixteenth century. One of the Variations evokes the musical heritage of the Basque region, characterized by rhythms in quintuple metre, a zortziko.

Similar to Turina, Villa-Lobos would become among the most successful “classical” composers who expressed the heritage of Brazil in music. However, virtually no trace of Brazilian folklore is found in his First Violin Sonata, which has indeed a distinctly French flavor. Villa-Lobos crossed the ocean to undertake musical studies in France, but only after the composition of this Sonata. Still, its melancholy mood (corresponding to its title “Despair”) is clearly allusive to fin-de-siècle French music.

Another fin-de-siècle (in this case, the end of the twentieth century) is represented by the most recent work of this CD, the Sonata para violino e piano. Written in 1995, by Brazilian composer Guilherme Bernstein in his late twenties, opens on an incisive motto, presented at the unison by the violin and piano. The first movement sees the dialectics between a lyrical Cantabile espressivo in tempo rubato and contrasting sections with a powerful rhythmical drive. Leitmotifs are disseminated throughout the score, which appears as tightly knitted. The second movement expands the initial motivic cells, embracing very small intervals, and broadens them to reach expressive climaxes enhanced by rhythmical tensions. The third movement is a virtuosic, galloping perpetuum mobile built on a ceaseless and breathtaking succession of semiquavers.

Together, these four works portray the inexhaustible potential of the Violin and Piano Sonata and underpin the inspiration it has created — and continues to create — on the greatest composers of all times.

Year 2021 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads