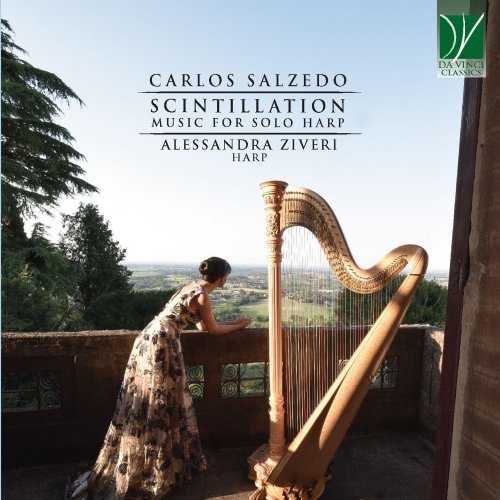

Alessandra Ziveri - Carlos Salzedo: Scintillation (Music for Solo Harp) (2021)

BAND/ARTIST: Alessandra Ziveri

- Title: Carlos Salzedo: Scintillation (Music for Solo Harp)

- Year Of Release: 2021

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 00:53:00

- Total Size: 195 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

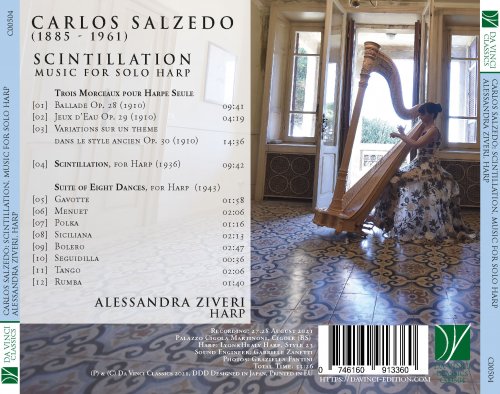

01. Trois Morceaux pour Harpe Seule, Op. 28: No. 1, Ballade

02. Trois Morceaux pour Harpe Seule, Op. 29: No. 2, Jeux d’Eau

03. Trois Morceaux pour Harpe Seule, Op. 30: No. 3, Variations sur un theme dans le style ancien

04. Scintillation

05. Suite of Eight Dances: I. Gavotte

06. Suite of Eight Dances: II. Menuet

07. Suite of Eight Dances: III. Polka

08. Suite of Eight Dances: IV. Siciliana

09. Suite of Eight Dances: V. Bolero

10. Suite of Eight Dances: VI. Seguidilla

11. Suite of Eight Dances: VII. Tango

12. Suite of Eight Dances: VIII. Rumba

In the harp world, few figures are better known than Carlos Salzedo; however, in the larger musical world, and even among classical music enthusiast, his biography and personality are not sufficiently discussed and appreciated. For this reason, this Da Vinci Classics album is a very welcome addition to the existing discography, and will enhance the fame of this great musician and pedagogue.

Even though Salzedo’s career and compositional activity are strictly connected to the harp, to limit his influence to the boundaries of the harp world is to dramatically downplay his role. As we will shortly see, his personality, principles and production were immensely influential and played a fundamental role in the development of twentieth-century music.

Carlos Salzedo was born on April 6th, 1885. He came from a Sephardic family, whose culture was deeply immersed in the fecund and original musical tradition of the Iberian Jews. At birth, he received the names of Charles Moïse Léon, but he would later be known simply as “Carlos”. This change mirrors his double, or rather triple or even quadruple national identity. He was born in France, and lived there for years; his family was rooted in the Spanish tradition, as his family name clearly reveals; their Jewish heritage was equally fundamental; and there was also a Basque cultural component which Salzedo was always ready to acknowledge.

His parents were both high-level professional musicians; moreover, their art had given them access to the aristocracy, and Salzedo’s mother used to be the court pianist to the Spanish Royal family during their summer holidays. On one such occasion, the Queen Mother, Maria Christina, had the opportunity to hear the first musical essays of little Carlos, who was barely three at the time; so impressed was she with his precocious accomplishment, that she was fond of calling him “my little Mozart”.

After further evidence of his musical talent, Carlos was encouraged in developing it through serious study. In order to facilitate his professionalization in the musical field, he was home-schooled; he quickly reached a very high level in piano proficiency. However, he sadly lost his mother when he was only five; following this event, the family moved to the Basque region, where the child was exposed to the warmth and to the very special culture of the local inhabitants, developing a fondness for all things Basque, and also for the particular rhythms found in their musical traditions.

Having completed his first musical training with great success, Carlos was admitted to the prestigious Conservatoire of Paris, at the early age of nine. There, he won multiple awards, prizes and recognitions, establishing himself as one of the most promising pupils of the era. When the time came for Carlos to take on a second instrument, the idea was suggested that the harp could be a suitable instrument for him. This would prove to be a momentous choice, but was also a rather uncommon one. The harp, up to that moment, was not an instrument on the same plane as, for example, the violin or the piano; it was mostly associated with salon music, and it was very common to refer to the harp as to a nice object of furniture rather than to an instrument proper. However, it was maintained that this choice could be profitable for Carlos, since his lungs seemed to be not sufficiently developed for taking on a wind instrument, and bowed string instruments were already represented, in the family, by his brother’s violin.

Within the space of very few months, at age eleven, Salzedo mastered the fundamentals of harp technique, and was therefore enrolled in the Conservatory class of the famous Alphonse Hasselmans (1845-1912). Hasselmans was one of the greatest harpists of the late nineteenth century, and was a very exacting, strict and demanding professor. As legend has it, he required a vast amount of new music to be memorized by his students every week. His lessons were public, attended by all of his students and by many of their parents; the scenes of his fury, when he was disappointed in a student’s performance, were famous throughout the coeval musical world.

Still, his guidance was crucial for young Salzedo, who became a real virtuoso of the instrument within just five years. At sixteen, Salzedo was the first and last student in the history of the Paris Conservatoire to win the First Prize in both piano and harp on the same day. With this exceptional feat, but also thanks to his great talent and skill, Salzedo conquered the attention of his contemporaries, including the director of the Paris Conservatoire, Gabriel Fauré. His fame circulated widely. On one occasion, he was turning pages to no less a musician than Maurice Ravel during a recording in which Ravel was playing the piano. A ferocious critic wrote that the result would have been better had the roles been reversed…

After his double graduation, Carlos Salzedo embarked in extensive concert tours, while moonlighting as an orchestra harpist in both classical and “lighter” settings; he was also active as a synagogue musician, taking his father’s post when needed. The appreciation of the Jewish community for the harp, historically associated to the king musician David, was probably one of the factors who eventually led Salzedo to focus his attention on the harp rather than on the piano.

Another element which certainly concurred in this choice was the interest demonstrated by Arturo Toscanini, who officially invited Salzedo to join the ranks of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra in New York, in 1909. Salzedo was quick to agree, even though he spoke not a word of English at the time of his arrival. However, due to his gift for the languages, and particularly to his lively and friendly personality, he quickly mastered the idiom and became the life and soul of many salons and parties of the American upper classes. He was capable to befriend many important personalities (such as Rockefeller) and to involve them – and the funds they managed – in his cultural projects.

He soon demonstrated his interest in the field of contemporary music. He worked in close contact with some of the major musicians of the era; they learnt from his increasingly daring explorations of harp technique, and he tirelessly promoted their music. Before World War I, Salzedo returned to Europe where he founded a trio with flutist Georges Barrère and cellist Paul Kéfer, with whom he toured extensively. The beginning of the war found him on French soil, so that he was drafted in the Army. During his service, he was able to create a musical society, with which he supported and enlivened the morale of his fellow combatants. However, he fell ill with pneumonia and after a slow recovery was authorized to return to the state of civilian.

Back in America, he took US citizenship and began an intense teaching activity, both at the Juilliard School and at the Curtis Institute. Along with these official appointments, he taught extensively on a semiprivate basis – meaning that many of his institutional students used to spend some time in his summer residence with him, in order to continue their studies under his guidance and within a more relaxed setting.

Throughout his activity, Salzedo developed many new techniques. He explored the full range of the harp’s possibilities: on the one hand, he responded to the need for new sounds which came from many contemporaneous composers; on the other, he stimulated their creativity through his innovative findings. These new techniques needed new symbols for notation, and these he also developed; he wrote methods which were used by both harpists and composers, and it is remarkable that some of the greatest musicians of the era admittedly took their cues from his musical ideas.

Salzedo’s technique did not aim only at the achievement of an extraordinary virtuosity, even though this is what he realized and transmitted to his students; he wished for the whole activity of sound production on the harp to become a “work of art” in its own right. For this purpose, he enlisted the help of legendary dancer and choreographer Vaslav Nijinski, with whom he developed a system of gestures which helped not only the production, but also the enjoyment and fruition of the sound, and consequently of music.

The works recorded here demonstrate the full palette of his musicianship, his inventiveness as a composer and the extraordinary techniques he developed. The Trois morceaux pour harpe seule were published by a 26-y.o. musician; they evoke the world of fin-de-siècle French music, with a touch of Impressionism and with a refined use of musical imagery. The narrative and poetic quality of the Ballade, the dazzling fascination of Jeux d’eau and the Neo-Classicist imprint of the Variations all concur in establishing his creativity and musicianship.

Scintillation, written in 1936, is another of his best-known compositions. It resumes dance schemes, but weaves them into a fascinating combination of expressivity and fantasy.

Other dance rhythms inform the scoring of his Suite of Eight Dances: here, the encounter between tradition and modernity is particularly evident. The first four dances are more Classicist in style, and the third (Polka) revives a theme Salzedo wrote in one of his very first compositions, composed at age five, and by the title of Moustique (Mosquito). The four last dances are more modern in style and reminiscent of the new rhythms and styles of Iberian and Latin-American music. One can discern the influence of musicians such as Poulenc or Milhaud in the two souls of the suite, the Neo-Classicist and the modernist, the irony and the vitalism.

Together, these works demonstrate the genius of Salzedo both as a composer and as a harpist; a genius for new sounds, a genius for combining them, a genius for finding new ways of producing them. A genius who opened up new ways for all those who consider the role of the harp in twentieth-century music.

01. Trois Morceaux pour Harpe Seule, Op. 28: No. 1, Ballade

02. Trois Morceaux pour Harpe Seule, Op. 29: No. 2, Jeux d’Eau

03. Trois Morceaux pour Harpe Seule, Op. 30: No. 3, Variations sur un theme dans le style ancien

04. Scintillation

05. Suite of Eight Dances: I. Gavotte

06. Suite of Eight Dances: II. Menuet

07. Suite of Eight Dances: III. Polka

08. Suite of Eight Dances: IV. Siciliana

09. Suite of Eight Dances: V. Bolero

10. Suite of Eight Dances: VI. Seguidilla

11. Suite of Eight Dances: VII. Tango

12. Suite of Eight Dances: VIII. Rumba

In the harp world, few figures are better known than Carlos Salzedo; however, in the larger musical world, and even among classical music enthusiast, his biography and personality are not sufficiently discussed and appreciated. For this reason, this Da Vinci Classics album is a very welcome addition to the existing discography, and will enhance the fame of this great musician and pedagogue.

Even though Salzedo’s career and compositional activity are strictly connected to the harp, to limit his influence to the boundaries of the harp world is to dramatically downplay his role. As we will shortly see, his personality, principles and production were immensely influential and played a fundamental role in the development of twentieth-century music.

Carlos Salzedo was born on April 6th, 1885. He came from a Sephardic family, whose culture was deeply immersed in the fecund and original musical tradition of the Iberian Jews. At birth, he received the names of Charles Moïse Léon, but he would later be known simply as “Carlos”. This change mirrors his double, or rather triple or even quadruple national identity. He was born in France, and lived there for years; his family was rooted in the Spanish tradition, as his family name clearly reveals; their Jewish heritage was equally fundamental; and there was also a Basque cultural component which Salzedo was always ready to acknowledge.

His parents were both high-level professional musicians; moreover, their art had given them access to the aristocracy, and Salzedo’s mother used to be the court pianist to the Spanish Royal family during their summer holidays. On one such occasion, the Queen Mother, Maria Christina, had the opportunity to hear the first musical essays of little Carlos, who was barely three at the time; so impressed was she with his precocious accomplishment, that she was fond of calling him “my little Mozart”.

After further evidence of his musical talent, Carlos was encouraged in developing it through serious study. In order to facilitate his professionalization in the musical field, he was home-schooled; he quickly reached a very high level in piano proficiency. However, he sadly lost his mother when he was only five; following this event, the family moved to the Basque region, where the child was exposed to the warmth and to the very special culture of the local inhabitants, developing a fondness for all things Basque, and also for the particular rhythms found in their musical traditions.

Having completed his first musical training with great success, Carlos was admitted to the prestigious Conservatoire of Paris, at the early age of nine. There, he won multiple awards, prizes and recognitions, establishing himself as one of the most promising pupils of the era. When the time came for Carlos to take on a second instrument, the idea was suggested that the harp could be a suitable instrument for him. This would prove to be a momentous choice, but was also a rather uncommon one. The harp, up to that moment, was not an instrument on the same plane as, for example, the violin or the piano; it was mostly associated with salon music, and it was very common to refer to the harp as to a nice object of furniture rather than to an instrument proper. However, it was maintained that this choice could be profitable for Carlos, since his lungs seemed to be not sufficiently developed for taking on a wind instrument, and bowed string instruments were already represented, in the family, by his brother’s violin.

Within the space of very few months, at age eleven, Salzedo mastered the fundamentals of harp technique, and was therefore enrolled in the Conservatory class of the famous Alphonse Hasselmans (1845-1912). Hasselmans was one of the greatest harpists of the late nineteenth century, and was a very exacting, strict and demanding professor. As legend has it, he required a vast amount of new music to be memorized by his students every week. His lessons were public, attended by all of his students and by many of their parents; the scenes of his fury, when he was disappointed in a student’s performance, were famous throughout the coeval musical world.

Still, his guidance was crucial for young Salzedo, who became a real virtuoso of the instrument within just five years. At sixteen, Salzedo was the first and last student in the history of the Paris Conservatoire to win the First Prize in both piano and harp on the same day. With this exceptional feat, but also thanks to his great talent and skill, Salzedo conquered the attention of his contemporaries, including the director of the Paris Conservatoire, Gabriel Fauré. His fame circulated widely. On one occasion, he was turning pages to no less a musician than Maurice Ravel during a recording in which Ravel was playing the piano. A ferocious critic wrote that the result would have been better had the roles been reversed…

After his double graduation, Carlos Salzedo embarked in extensive concert tours, while moonlighting as an orchestra harpist in both classical and “lighter” settings; he was also active as a synagogue musician, taking his father’s post when needed. The appreciation of the Jewish community for the harp, historically associated to the king musician David, was probably one of the factors who eventually led Salzedo to focus his attention on the harp rather than on the piano.

Another element which certainly concurred in this choice was the interest demonstrated by Arturo Toscanini, who officially invited Salzedo to join the ranks of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra in New York, in 1909. Salzedo was quick to agree, even though he spoke not a word of English at the time of his arrival. However, due to his gift for the languages, and particularly to his lively and friendly personality, he quickly mastered the idiom and became the life and soul of many salons and parties of the American upper classes. He was capable to befriend many important personalities (such as Rockefeller) and to involve them – and the funds they managed – in his cultural projects.

He soon demonstrated his interest in the field of contemporary music. He worked in close contact with some of the major musicians of the era; they learnt from his increasingly daring explorations of harp technique, and he tirelessly promoted their music. Before World War I, Salzedo returned to Europe where he founded a trio with flutist Georges Barrère and cellist Paul Kéfer, with whom he toured extensively. The beginning of the war found him on French soil, so that he was drafted in the Army. During his service, he was able to create a musical society, with which he supported and enlivened the morale of his fellow combatants. However, he fell ill with pneumonia and after a slow recovery was authorized to return to the state of civilian.

Back in America, he took US citizenship and began an intense teaching activity, both at the Juilliard School and at the Curtis Institute. Along with these official appointments, he taught extensively on a semiprivate basis – meaning that many of his institutional students used to spend some time in his summer residence with him, in order to continue their studies under his guidance and within a more relaxed setting.

Throughout his activity, Salzedo developed many new techniques. He explored the full range of the harp’s possibilities: on the one hand, he responded to the need for new sounds which came from many contemporaneous composers; on the other, he stimulated their creativity through his innovative findings. These new techniques needed new symbols for notation, and these he also developed; he wrote methods which were used by both harpists and composers, and it is remarkable that some of the greatest musicians of the era admittedly took their cues from his musical ideas.

Salzedo’s technique did not aim only at the achievement of an extraordinary virtuosity, even though this is what he realized and transmitted to his students; he wished for the whole activity of sound production on the harp to become a “work of art” in its own right. For this purpose, he enlisted the help of legendary dancer and choreographer Vaslav Nijinski, with whom he developed a system of gestures which helped not only the production, but also the enjoyment and fruition of the sound, and consequently of music.

The works recorded here demonstrate the full palette of his musicianship, his inventiveness as a composer and the extraordinary techniques he developed. The Trois morceaux pour harpe seule were published by a 26-y.o. musician; they evoke the world of fin-de-siècle French music, with a touch of Impressionism and with a refined use of musical imagery. The narrative and poetic quality of the Ballade, the dazzling fascination of Jeux d’eau and the Neo-Classicist imprint of the Variations all concur in establishing his creativity and musicianship.

Scintillation, written in 1936, is another of his best-known compositions. It resumes dance schemes, but weaves them into a fascinating combination of expressivity and fantasy.

Other dance rhythms inform the scoring of his Suite of Eight Dances: here, the encounter between tradition and modernity is particularly evident. The first four dances are more Classicist in style, and the third (Polka) revives a theme Salzedo wrote in one of his very first compositions, composed at age five, and by the title of Moustique (Mosquito). The four last dances are more modern in style and reminiscent of the new rhythms and styles of Iberian and Latin-American music. One can discern the influence of musicians such as Poulenc or Milhaud in the two souls of the suite, the Neo-Classicist and the modernist, the irony and the vitalism.

Together, these works demonstrate the genius of Salzedo both as a composer and as a harpist; a genius for new sounds, a genius for combining them, a genius for finding new ways of producing them. A genius who opened up new ways for all those who consider the role of the harp in twentieth-century music.

Year 2021 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads