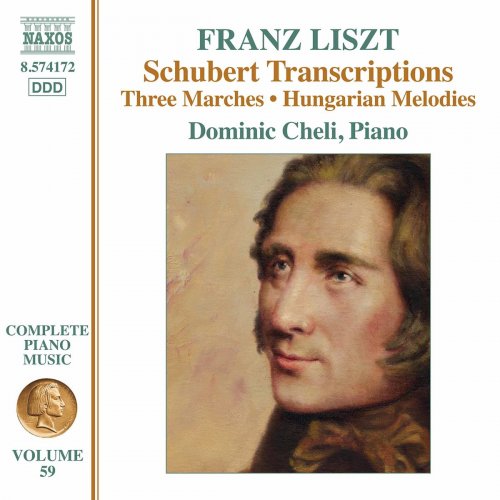

Dominic Cheli - Liszt: Schubert Transcriptions (2021)

BAND/ARTIST: Dominic Cheli

- Title: Liszt: Schubert Transcriptions

- Year Of Release: 2021

- Label: Naxos

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 01:19:35

- Total Size: 216 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

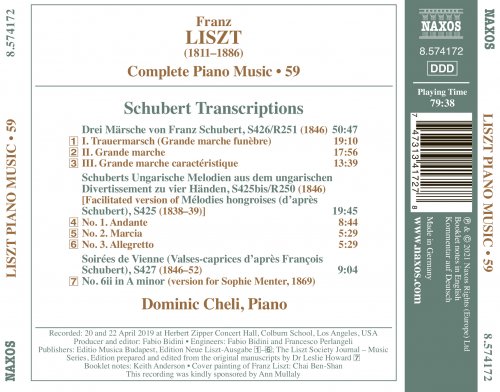

01. 3 Märsche von Franz Schubert, S. 426: No. 1, Trauermarsch

02. 3 Märsche von Franz Schubert, S. 426: No. 2, Grande marche

03. 3 Märsche von Franz Schubert, S. 426: No. 3, Grande marche caractéristique

04. Mélodies hongroises d'après Franz Schubert, S. 425a: No. 1, Andante

05. Mélodies hongroises d'après Franz Schubert, S. 425a: No. 2, Marcia

06. Mélodies hongroises d'après Franz Schubert, S. 425a: No. 3, Allegretto

07. Soirées de Vienne, S. 427: No. 6 in A Minor (After Schubert's D. 969 & 779) [1869 Version]

Franz Liszt was born at Raiding in a German-speaking region of Hungary. His father, Adam Liszt, was a steward in the employment of Haydn’s former patrons, the Esterházy Princes, and an amateur cellist. The boy showed early musical talent, and with the support of members of the Hungarian nobility was able to move with his parents to Vienna, where he took piano lessons from Czerny and composition lessons from the old Court Composer Antonio Salieri, who had taught Beethoven and Schubert. In 1822 the Liszts moved to Paris, where, as a foreigner, Franz was refused admission to the Conservatoire by Cherubini, but was able to embark on a career as a virtuoso, with the help of the piano manufacturer Erard.

On the death of his father in 1827 Liszt was joined again by his mother in Paris, where he began to teach the piano and to interest himself in the newest literary trends of the day. The appearance of Paganini there in 1831 suggested new possibilities of virtuosity as a pianist, later exemplified in his Paganini Studies. A liaison with a married woman, the Comtesse Marie d’Agoult, a bluestocking on the model of their friend the novelist George Sand (Aurore Dudevant), and the subsequent births of three children, involved Liszt in years of travel, from 1839 once more as a virtuoso pianist, a role in which he came to enjoy the wildest adulation of audiences.

In 1844 Liszt finally broke with Marie d’Agoult, who later took her own literary revenge on her lover. Connection with the small Grand Duchy of Weimar led in 1848 to his withdrawal from public concerts and his establishment there as Director of Music, accompanied by a young Polish heiress, Princess Carolyne zu Sayn- Wittgenstein, the estranged wife of a Russian nobleman and a woman of literary and theological propensities. Liszt now turned his attention to new forms of composition, particularly to symphonic poems, in which he attempted to translate into musical terms works of literature and other subjects.

Catholic marriage to Princess Sayn-Wittgenstein had proved impossible, but application to the Vatican offered some hope, when, in 1861, Liszt travelled to join her in Rome. The marriage did not take place and the couple continued to live separately in Rome, starting a period of his life that Liszt later described as une vie trifurquée (‘a three-pronged life’), as he divided his time between his comfortable monastic residence in Rome, his visits to Weimar, where he held court as a master of the keyboard and a prophet of the new music, and his appearances in Hungary, where he was now hailed as a national hero. He died in 1886 in Bayreuth during the Wagner Festival, now controlled, since her husband’s death, by his daughter Cosima, to whom his appearance there seems to have been less than welcome.

It is strange to think that while Liszt was in Vienna in 1822 and 1823, allegedly kissed by Beethoven and certainly taught by Czerny and Salieri, Schubert had won a reputation for himself in his own different circle of friends. It was in his later years that Liszt did much to introduce Schubert’s work to a wider public through his own transcriptions. The Three Marches, S426/R251, are transcribed by Liszt from a set of six marches for piano duet, dedicated on their publication in 1825 to Schubert’s doctor. Liszt’s transcriptions are dated 1846. The first of the set is a Funeral march, a form for which Beethoven provided various examples.

The Mélodies hongroises (d’après Schubert), again transcribed from a version for piano duet, consist of three movements, taken from Schubert’s Divertissement à la hongroise, Op. 54, D. 818 (easier version, Diabelli, 1746). Schubert’s occasional interest in the music of Hungary reflects his experience during summer holidays spent teaching the two daughters of Count Johann Esterházy at Zeliz in 1818 and 1824. The Divertissement belongs to the second of these visits, with Liszt’s transcription published in Vienna in 1846.

Liszt’s Soirées de Vienne (Valse-caprices d’après François Schubert), a set of nine pieces, some of which were to feature frequently in Liszt’s performance programmes, were written between 1946 and 1852. No. 6 in A minor was revised by Liszt, with a further version written in 1869, and is said to have been part of the last recital he gave, in Luxemburg in July 1886. The final version of No. 6 was revised again for the composer’s pupil, Sophie Menter, a pianist Liszt proclaimed to be his successor – not the only pupil to win this accolade. The daughter of a cellist, Menter married the cellist David Popper and had enjoyed earlier connection with Liszt through his pupils Karl Tausig and Hans von Bülow. After Liszt’s death she continued a successful career as a pianist and was regarded by some as the incarnation of Liszt.

01. 3 Märsche von Franz Schubert, S. 426: No. 1, Trauermarsch

02. 3 Märsche von Franz Schubert, S. 426: No. 2, Grande marche

03. 3 Märsche von Franz Schubert, S. 426: No. 3, Grande marche caractéristique

04. Mélodies hongroises d'après Franz Schubert, S. 425a: No. 1, Andante

05. Mélodies hongroises d'après Franz Schubert, S. 425a: No. 2, Marcia

06. Mélodies hongroises d'après Franz Schubert, S. 425a: No. 3, Allegretto

07. Soirées de Vienne, S. 427: No. 6 in A Minor (After Schubert's D. 969 & 779) [1869 Version]

Franz Liszt was born at Raiding in a German-speaking region of Hungary. His father, Adam Liszt, was a steward in the employment of Haydn’s former patrons, the Esterházy Princes, and an amateur cellist. The boy showed early musical talent, and with the support of members of the Hungarian nobility was able to move with his parents to Vienna, where he took piano lessons from Czerny and composition lessons from the old Court Composer Antonio Salieri, who had taught Beethoven and Schubert. In 1822 the Liszts moved to Paris, where, as a foreigner, Franz was refused admission to the Conservatoire by Cherubini, but was able to embark on a career as a virtuoso, with the help of the piano manufacturer Erard.

On the death of his father in 1827 Liszt was joined again by his mother in Paris, where he began to teach the piano and to interest himself in the newest literary trends of the day. The appearance of Paganini there in 1831 suggested new possibilities of virtuosity as a pianist, later exemplified in his Paganini Studies. A liaison with a married woman, the Comtesse Marie d’Agoult, a bluestocking on the model of their friend the novelist George Sand (Aurore Dudevant), and the subsequent births of three children, involved Liszt in years of travel, from 1839 once more as a virtuoso pianist, a role in which he came to enjoy the wildest adulation of audiences.

In 1844 Liszt finally broke with Marie d’Agoult, who later took her own literary revenge on her lover. Connection with the small Grand Duchy of Weimar led in 1848 to his withdrawal from public concerts and his establishment there as Director of Music, accompanied by a young Polish heiress, Princess Carolyne zu Sayn- Wittgenstein, the estranged wife of a Russian nobleman and a woman of literary and theological propensities. Liszt now turned his attention to new forms of composition, particularly to symphonic poems, in which he attempted to translate into musical terms works of literature and other subjects.

Catholic marriage to Princess Sayn-Wittgenstein had proved impossible, but application to the Vatican offered some hope, when, in 1861, Liszt travelled to join her in Rome. The marriage did not take place and the couple continued to live separately in Rome, starting a period of his life that Liszt later described as une vie trifurquée (‘a three-pronged life’), as he divided his time between his comfortable monastic residence in Rome, his visits to Weimar, where he held court as a master of the keyboard and a prophet of the new music, and his appearances in Hungary, where he was now hailed as a national hero. He died in 1886 in Bayreuth during the Wagner Festival, now controlled, since her husband’s death, by his daughter Cosima, to whom his appearance there seems to have been less than welcome.

It is strange to think that while Liszt was in Vienna in 1822 and 1823, allegedly kissed by Beethoven and certainly taught by Czerny and Salieri, Schubert had won a reputation for himself in his own different circle of friends. It was in his later years that Liszt did much to introduce Schubert’s work to a wider public through his own transcriptions. The Three Marches, S426/R251, are transcribed by Liszt from a set of six marches for piano duet, dedicated on their publication in 1825 to Schubert’s doctor. Liszt’s transcriptions are dated 1846. The first of the set is a Funeral march, a form for which Beethoven provided various examples.

The Mélodies hongroises (d’après Schubert), again transcribed from a version for piano duet, consist of three movements, taken from Schubert’s Divertissement à la hongroise, Op. 54, D. 818 (easier version, Diabelli, 1746). Schubert’s occasional interest in the music of Hungary reflects his experience during summer holidays spent teaching the two daughters of Count Johann Esterházy at Zeliz in 1818 and 1824. The Divertissement belongs to the second of these visits, with Liszt’s transcription published in Vienna in 1846.

Liszt’s Soirées de Vienne (Valse-caprices d’après François Schubert), a set of nine pieces, some of which were to feature frequently in Liszt’s performance programmes, were written between 1946 and 1852. No. 6 in A minor was revised by Liszt, with a further version written in 1869, and is said to have been part of the last recital he gave, in Luxemburg in July 1886. The final version of No. 6 was revised again for the composer’s pupil, Sophie Menter, a pianist Liszt proclaimed to be his successor – not the only pupil to win this accolade. The daughter of a cellist, Menter married the cellist David Popper and had enjoyed earlier connection with Liszt through his pupils Karl Tausig and Hans von Bülow. After Liszt’s death she continued a successful career as a pianist and was regarded by some as the incarnation of Liszt.

Year 2021 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads