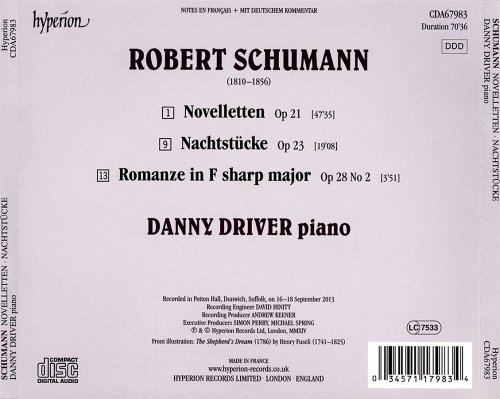

Danny Driver - Schumann: Novelletten Op. 21, Nachtstücke Op. 23 (2014)

BAND/ARTIST: Danny Driver

- Title: Schumann: Novelletten Op. 21, Nachtstücke Op. 23

- Year Of Release: 2014

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical, Piano

- Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

- Total Time: 01:10:28

- Total Size: 196 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

Novelletten Op 21 [47'35]

1 No 1 in F major: Markiert und kräftig[5'24]

2 No 2 in D major: Äusserst rasch und mit Bravour[6'30]

3 No 3 in D major: Leicht und mit Humor[4'29]

4 No 4 in D major: Ballmäßig, sehr munter[3'31]

5 No 5 in D major: Rauschend und festlich[9'20]

6 No 6 in A major: Sehr lebhaft, mit vielem Humor[4'13]

7 No 7 in E major: Äusserst rasch[3'01]

8 No 8 in F sharp minor: Sehr lebhaft[11'07]

Nachtstücke Op 23 [19'08]

9 No 1 in C major: Mehr langsam, oft zurückhaltend[6'02]

10 No 2 in F major: Markiert und lebhaft[5'26]

11 No 3 in D flat major: Mit grosser Lebhaftigkeit[3'56]

12 No 4 in F major: Einfach[3'44]

Drei Romanzen Op 28

13 No 2 in F sharp major: Einfach[3'51]

Novelletten Op 21 [47'35]

1 No 1 in F major: Markiert und kräftig[5'24]

2 No 2 in D major: Äusserst rasch und mit Bravour[6'30]

3 No 3 in D major: Leicht und mit Humor[4'29]

4 No 4 in D major: Ballmäßig, sehr munter[3'31]

5 No 5 in D major: Rauschend und festlich[9'20]

6 No 6 in A major: Sehr lebhaft, mit vielem Humor[4'13]

7 No 7 in E major: Äusserst rasch[3'01]

8 No 8 in F sharp minor: Sehr lebhaft[11'07]

Nachtstücke Op 23 [19'08]

9 No 1 in C major: Mehr langsam, oft zurückhaltend[6'02]

10 No 2 in F major: Markiert und lebhaft[5'26]

11 No 3 in D flat major: Mit grosser Lebhaftigkeit[3'56]

12 No 4 in F major: Einfach[3'44]

Drei Romanzen Op 28

13 No 2 in F sharp major: Einfach[3'51]

In the autumn of 1838 Schumann moved to Vienna in the hope of finding a publisher there for the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, of which he was editor. He also wanted to establish a future home in the Austrian capital for himself and his fiancée, Clara Wieck. Neither of these ambitions was realized, and Schumann found himself having to cut his visit short. In the middle of April 1839, some ten days after he left the city, he told Clara about a cycle of pieces which he had begun to compose:

I wrote to you about a premonition. I had it in the days from 24th to 27th March, during my new composition. There is a passage which keeps coming back, to which I kept returning. It is as though someone were sighing with a heavy heart: ‘Oh God!’ While composing, I kept seeing funeral processions, coffins, unhappy, despairing people, and when I had finished and had long sought a title I kept coming to Leichenphantasie [corpse-fantasy]. Isn’t that curious? While I was composing I was often so overcome that tears came forth and I really didn’t know why and had no reason for them. Then Therese’s letter arrived, and it stood clearly before me.

Therese was Schumann’s sister-in-law. Her letter informed him that his brother Eduard was seriously ill. Convinced that he would never see Eduard again, Schumann hurried away from Vienna. On the way home, he distinctly heard in his mind the sound of a funeral chorale played by trombones. As he later found out, that was the precise moment when his brother had died.

Schumann eventually called his new pieces Nachtstücke, borrowing his title, not for the first time, from ETA Hoffmann. He originally gave a separate heading to each of the four pieces in the cycle, though these were suppressed in the first edition: ‘Trauerzug’ (Funeral procession), ‘Kuriose Gesellschaft’ (Strange company), ‘Nächtliche Gelage’ (Nocturnal revelries) and ‘Rundgesang mit Solostimmen’ (Round with solo voices).

The funeral procession of Schumann’s opening piece is one that advances with hesitant steps. The cortège seems, moreover, to have started out of earshot, with the music beginning as though midstream. During the course of the piece it draws gradually nearer, until shortly before the close it is heard fortissimo, in chords whose widely spaced keyboard layout anticipates the texture of the final piece in Schumann’s collection. At the end, the procession recedes once more into the distance—so much so that we cannot be quite sure of having caught the sound of the delayed final chord.

The main subject of the second piece seems to bring with it the sound of laughter in the chortling accents of the main theme. The entire number is based on the descending scale pattern of this theme, which itself is like an accelerated parody of the funeral procession we have just heard. During the course of the piece Schumann manages to transform the motif into an elegant, lyrical interlude, into a recitative and—in inverted form—into a chuckling intermezzo, before the whole thing is finally brushed aside with a dismissive gesture.

The penultimate piece, with its first episode in an agitated minor key, seems to rush past us like the wind; and having begun in a tempo of great liveliness, the music’s pace increases for a second episode whose sweeping gestures soon give way to two-note phrases which cut across the triple-time beat, introducing an atmosphere of still greater breathlessness.

If the title Schumann at one stage thought of giving the first of his Nachtstücke had distinctly Mahlerian undertones, then the final piece in the collection is one that Mahler may actually have known. Its opening bars are strikingly similar to the refrain which punctuates the second of the two ‘Nachtmusik’ movements in the later composer’s Seventh Symphony. The inspired melody that follows begins with a yearning ascending interval in a rhythm that later forms the springboard for a sensuous middle section; until, with great subtlety, the closing notes of that middle section overlap with the return of the sighing initial phrase of the piece. In the final bars, as the gentle pizzicato of the opening theme becomes progressively smoother, the poet speaks, allowing the music to sink to a subdued close at the bottom of the keyboard.

Together with the set of Drei Romanzen, Op 28, the Nachtstücke marked the end of a long period during which Schumann had concentrated exclusively on piano music. The second Romanze from Op 28, in the radiant key of F sharp major, is the most hauntingly beautiful farewell to the keyboard one could imagine. Its gentle melody unfolds at first in the tenor voice, played in parallel by the thumbs of both hands, while above and below it an accompaniment in a ‘rocking’ motion lends the music the character of a lullaby. Following a contrasting section in which the melodic focus shifts to the top of the texture, the opening theme makes a return—only to be cut short, as Schumann introduces an imitative passage in recitative style. At the end, the music fades away with a reiteration of the tail-end of the melody’s opening phrase.

The title of the Novelletten, Op 21 was suggested to Schumann at least in part by the name of Clara—not his own bride-to-be, however, but the English singer Clara Novello, whom Mendelssohn had brought to Leipzig as a guest artist at the opera. At the same time, yet another Clara, or Clärchen, was in his mind: the heroine of Goethe’s drama Egmont. As Schumann explained to his own Clara at the beginning of February 1838:

I have composed a frightful amount for you in the last three weeks: light-hearted things, Egmont stories, family scenes with fathers, a wedding—in short, the most amiable things; and have named the whole work ‘Novelletten’, because you are called Clara and ‘Wiecketten’ doesn’t have a good enough ring to it.

In the end, to avoid any friction on the home front, Schumann dedicated the Novelletten to neither Clara, but instead to the pianist Adolph Henselt, with whom he had spent an agreeable Christmas Eve the previous year. Henselt subsequently moved to St Petersburg, where the Schumanns met him during their Russian tour in 1844. But by then they found he had become ‘impossibly pedantic’.

The Novelletten form what is at once the largest and the least known among Schumann’s major piano cycles. The music itself is of consistently high quality (years later, Schumann himself still regarded this among his most successful works), and clearly written in an exultant mood. Its main key is D major, though, as he so often liked to do, Schumann begins away from that basic key, with a piece that provides no hint of the tonal focus to come. That first number, indeed, modulates so relentlessly that no single key is established at all until the onset of its F major trio section. The opening march-like idea encapsulates the tonal plan of the piece as a whole: although the music progresses in a single sweep, it cadences firmly three times—first into F major, then into D flat major, and finally A major. These are the keys in which the contrasting episodes are set: first, a soaring F major melody above an accompaniment in smooth triplets; then a densely contrapuntal passage based on descending scale patterns (following this episode, the initial march theme makes the briefest of returns with the music still in D flat major); and finally a reprise of the first episode, this time in A major.

Schumann’s sketch for the second Novellette describes it as ‘Sarazene und Suleika’—a reference to the two central characters of Goethe’s collection of poems called the West-östlicher Divan. The Saracen is the singer and poet Hatem, depicted in the outer sections of Schumann’s piece with their virtuoso staccato arpeggio figures. Suleika appears in the slower middle section, and her calming influence clearly exerts its pull over Hatem: the return to his agitated material unfolds at first in a sustained pianissimo. Schumann sent this piece to Liszt, whose flamboyant keyboard manner may perhaps have prompted the tempo marking of the outer sections in the first place: Äusserst rasch und mit Bravour. Schumann heard Liszt play the Novellette in Leipzig, in March 1840, and reported to Clara: ‘The 2nd Novellette gave me great joy; you can scarcely believe what an effect it makes. He [Liszt] wants to play it in his third concert here, too.’

No less of a virtuoso piece is the third number of the cycle (for Schumann, this was a ‘Macbeth-Novellette’), with the light, staccato sonority of its outer sections bringing with them a hint of the Mendelssohnian scherzo style. The music begins momentarily as though it is to be in B minor—a suggestion that is strengthened by the actual use of that key in the wildly agitated, syncopated intermezzo which forms the central portion of the piece.

The fourth Novellette takes us straight into the ballroom, where a waltz of almost manic cheerfulness is unfolding. Gradually the pace of the swirling music increases—first, through an intensifying of its rate of harmonic change, until we reach a splendidly uplifting shift of key taking us from D into C major; and then through an actual acceleration of tempo leading ultimately to a series of crashing chords which momentarily subverts the waltz rhythm.

It is tempting to discern a barely disguised expression of anger in the ‘noisy’ polonaise (Rauschend und festlich is Schumann’s marking), with its stamping rhythm, that forms the fifth of the Novelletten. The music, with its off-beat accents, is agitated and restless, and its central episode expounds on the stamping rhythm with wrist-breaking obstinacy. At the end, the rhythmic motif, with its characteristic minor-major alternation, recedes into the distance, as though with a deep sigh of regret.

The sixth Novellette is a piece that presents a continual acceleration. Characteristically opening on a dissonance, it is a whirlwind kaleidoscope of contrasting moods coupled with a bewildering succession of keys. At the end, as the music threatens to spiral out of control, Schumann sounds the notes of the violin’s ‘open’ strings, as though in an attempt to bring some order into the tonal chaos. But before he can do so, the piece abruptly disappears in a puff of smoke.

The beautiful floating melody of the middle section in the cycle’s penultimate piece offers brief respite from all the frenetic activity, but this is otherwise another scherzo which rushes past without pausing to draw breath.

As for the last of the Novelletten, it is at once the longest and formally the most complex piece in the collection. It sets out as a passionately agitated piece in F sharp minor, with two trios—the first of them in D flat major; the second, with its imitation of hunting horns, in a bright D major. However, the second trio does not lead, as had the first, to a return of the opening material. Instead, the mood changes to one of intimacy, and above the pervasive dotted rhythm Schumann introduces a smooth melody which he describes as a ‘voice from afar’. The distant voice quotes the ‘Notturno’ from Clara Wieck’s Soirées musicales, Op 6, and at this point the music sinks as though towards a resigned D major conclusion. But instead, Schumann embarks on what appears to be an entirely fresh departure—one that is, however, significantly marked Fortsetzung und Schluss (continuation and ending). Its integration with the earlier, apparently self-contained, portion of the piece is assured by the reintroduction of the ‘voice from afar’ in a more emphatic form during the closing pages. Nevertheless, in a remarkable instance of ‘progressive’ tonality, the music ends not in the key of its beginning, but in D major—the principal key of the cycle as a whole.

I wrote to you about a premonition. I had it in the days from 24th to 27th March, during my new composition. There is a passage which keeps coming back, to which I kept returning. It is as though someone were sighing with a heavy heart: ‘Oh God!’ While composing, I kept seeing funeral processions, coffins, unhappy, despairing people, and when I had finished and had long sought a title I kept coming to Leichenphantasie [corpse-fantasy]. Isn’t that curious? While I was composing I was often so overcome that tears came forth and I really didn’t know why and had no reason for them. Then Therese’s letter arrived, and it stood clearly before me.

Therese was Schumann’s sister-in-law. Her letter informed him that his brother Eduard was seriously ill. Convinced that he would never see Eduard again, Schumann hurried away from Vienna. On the way home, he distinctly heard in his mind the sound of a funeral chorale played by trombones. As he later found out, that was the precise moment when his brother had died.

Schumann eventually called his new pieces Nachtstücke, borrowing his title, not for the first time, from ETA Hoffmann. He originally gave a separate heading to each of the four pieces in the cycle, though these were suppressed in the first edition: ‘Trauerzug’ (Funeral procession), ‘Kuriose Gesellschaft’ (Strange company), ‘Nächtliche Gelage’ (Nocturnal revelries) and ‘Rundgesang mit Solostimmen’ (Round with solo voices).

The funeral procession of Schumann’s opening piece is one that advances with hesitant steps. The cortège seems, moreover, to have started out of earshot, with the music beginning as though midstream. During the course of the piece it draws gradually nearer, until shortly before the close it is heard fortissimo, in chords whose widely spaced keyboard layout anticipates the texture of the final piece in Schumann’s collection. At the end, the procession recedes once more into the distance—so much so that we cannot be quite sure of having caught the sound of the delayed final chord.

The main subject of the second piece seems to bring with it the sound of laughter in the chortling accents of the main theme. The entire number is based on the descending scale pattern of this theme, which itself is like an accelerated parody of the funeral procession we have just heard. During the course of the piece Schumann manages to transform the motif into an elegant, lyrical interlude, into a recitative and—in inverted form—into a chuckling intermezzo, before the whole thing is finally brushed aside with a dismissive gesture.

The penultimate piece, with its first episode in an agitated minor key, seems to rush past us like the wind; and having begun in a tempo of great liveliness, the music’s pace increases for a second episode whose sweeping gestures soon give way to two-note phrases which cut across the triple-time beat, introducing an atmosphere of still greater breathlessness.

If the title Schumann at one stage thought of giving the first of his Nachtstücke had distinctly Mahlerian undertones, then the final piece in the collection is one that Mahler may actually have known. Its opening bars are strikingly similar to the refrain which punctuates the second of the two ‘Nachtmusik’ movements in the later composer’s Seventh Symphony. The inspired melody that follows begins with a yearning ascending interval in a rhythm that later forms the springboard for a sensuous middle section; until, with great subtlety, the closing notes of that middle section overlap with the return of the sighing initial phrase of the piece. In the final bars, as the gentle pizzicato of the opening theme becomes progressively smoother, the poet speaks, allowing the music to sink to a subdued close at the bottom of the keyboard.

Together with the set of Drei Romanzen, Op 28, the Nachtstücke marked the end of a long period during which Schumann had concentrated exclusively on piano music. The second Romanze from Op 28, in the radiant key of F sharp major, is the most hauntingly beautiful farewell to the keyboard one could imagine. Its gentle melody unfolds at first in the tenor voice, played in parallel by the thumbs of both hands, while above and below it an accompaniment in a ‘rocking’ motion lends the music the character of a lullaby. Following a contrasting section in which the melodic focus shifts to the top of the texture, the opening theme makes a return—only to be cut short, as Schumann introduces an imitative passage in recitative style. At the end, the music fades away with a reiteration of the tail-end of the melody’s opening phrase.

The title of the Novelletten, Op 21 was suggested to Schumann at least in part by the name of Clara—not his own bride-to-be, however, but the English singer Clara Novello, whom Mendelssohn had brought to Leipzig as a guest artist at the opera. At the same time, yet another Clara, or Clärchen, was in his mind: the heroine of Goethe’s drama Egmont. As Schumann explained to his own Clara at the beginning of February 1838:

I have composed a frightful amount for you in the last three weeks: light-hearted things, Egmont stories, family scenes with fathers, a wedding—in short, the most amiable things; and have named the whole work ‘Novelletten’, because you are called Clara and ‘Wiecketten’ doesn’t have a good enough ring to it.

In the end, to avoid any friction on the home front, Schumann dedicated the Novelletten to neither Clara, but instead to the pianist Adolph Henselt, with whom he had spent an agreeable Christmas Eve the previous year. Henselt subsequently moved to St Petersburg, where the Schumanns met him during their Russian tour in 1844. But by then they found he had become ‘impossibly pedantic’.

The Novelletten form what is at once the largest and the least known among Schumann’s major piano cycles. The music itself is of consistently high quality (years later, Schumann himself still regarded this among his most successful works), and clearly written in an exultant mood. Its main key is D major, though, as he so often liked to do, Schumann begins away from that basic key, with a piece that provides no hint of the tonal focus to come. That first number, indeed, modulates so relentlessly that no single key is established at all until the onset of its F major trio section. The opening march-like idea encapsulates the tonal plan of the piece as a whole: although the music progresses in a single sweep, it cadences firmly three times—first into F major, then into D flat major, and finally A major. These are the keys in which the contrasting episodes are set: first, a soaring F major melody above an accompaniment in smooth triplets; then a densely contrapuntal passage based on descending scale patterns (following this episode, the initial march theme makes the briefest of returns with the music still in D flat major); and finally a reprise of the first episode, this time in A major.

Schumann’s sketch for the second Novellette describes it as ‘Sarazene und Suleika’—a reference to the two central characters of Goethe’s collection of poems called the West-östlicher Divan. The Saracen is the singer and poet Hatem, depicted in the outer sections of Schumann’s piece with their virtuoso staccato arpeggio figures. Suleika appears in the slower middle section, and her calming influence clearly exerts its pull over Hatem: the return to his agitated material unfolds at first in a sustained pianissimo. Schumann sent this piece to Liszt, whose flamboyant keyboard manner may perhaps have prompted the tempo marking of the outer sections in the first place: Äusserst rasch und mit Bravour. Schumann heard Liszt play the Novellette in Leipzig, in March 1840, and reported to Clara: ‘The 2nd Novellette gave me great joy; you can scarcely believe what an effect it makes. He [Liszt] wants to play it in his third concert here, too.’

No less of a virtuoso piece is the third number of the cycle (for Schumann, this was a ‘Macbeth-Novellette’), with the light, staccato sonority of its outer sections bringing with them a hint of the Mendelssohnian scherzo style. The music begins momentarily as though it is to be in B minor—a suggestion that is strengthened by the actual use of that key in the wildly agitated, syncopated intermezzo which forms the central portion of the piece.

The fourth Novellette takes us straight into the ballroom, where a waltz of almost manic cheerfulness is unfolding. Gradually the pace of the swirling music increases—first, through an intensifying of its rate of harmonic change, until we reach a splendidly uplifting shift of key taking us from D into C major; and then through an actual acceleration of tempo leading ultimately to a series of crashing chords which momentarily subverts the waltz rhythm.

It is tempting to discern a barely disguised expression of anger in the ‘noisy’ polonaise (Rauschend und festlich is Schumann’s marking), with its stamping rhythm, that forms the fifth of the Novelletten. The music, with its off-beat accents, is agitated and restless, and its central episode expounds on the stamping rhythm with wrist-breaking obstinacy. At the end, the rhythmic motif, with its characteristic minor-major alternation, recedes into the distance, as though with a deep sigh of regret.

The sixth Novellette is a piece that presents a continual acceleration. Characteristically opening on a dissonance, it is a whirlwind kaleidoscope of contrasting moods coupled with a bewildering succession of keys. At the end, as the music threatens to spiral out of control, Schumann sounds the notes of the violin’s ‘open’ strings, as though in an attempt to bring some order into the tonal chaos. But before he can do so, the piece abruptly disappears in a puff of smoke.

The beautiful floating melody of the middle section in the cycle’s penultimate piece offers brief respite from all the frenetic activity, but this is otherwise another scherzo which rushes past without pausing to draw breath.

As for the last of the Novelletten, it is at once the longest and formally the most complex piece in the collection. It sets out as a passionately agitated piece in F sharp minor, with two trios—the first of them in D flat major; the second, with its imitation of hunting horns, in a bright D major. However, the second trio does not lead, as had the first, to a return of the opening material. Instead, the mood changes to one of intimacy, and above the pervasive dotted rhythm Schumann introduces a smooth melody which he describes as a ‘voice from afar’. The distant voice quotes the ‘Notturno’ from Clara Wieck’s Soirées musicales, Op 6, and at this point the music sinks as though towards a resigned D major conclusion. But instead, Schumann embarks on what appears to be an entirely fresh departure—one that is, however, significantly marked Fortsetzung und Schluss (continuation and ending). Its integration with the earlier, apparently self-contained, portion of the piece is assured by the reintroduction of the ‘voice from afar’ in a more emphatic form during the closing pages. Nevertheless, in a remarkable instance of ‘progressive’ tonality, the music ends not in the key of its beginning, but in D major—the principal key of the cycle as a whole.

Download Link Isra.Cloud

Danny Driver - Schumann: Novelletten Op. 21, Nachtstücke Op. 23 (2014)

My blog

Danny Driver - Schumann: Novelletten Op. 21, Nachtstücke Op. 23 (2014)

My blog

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads