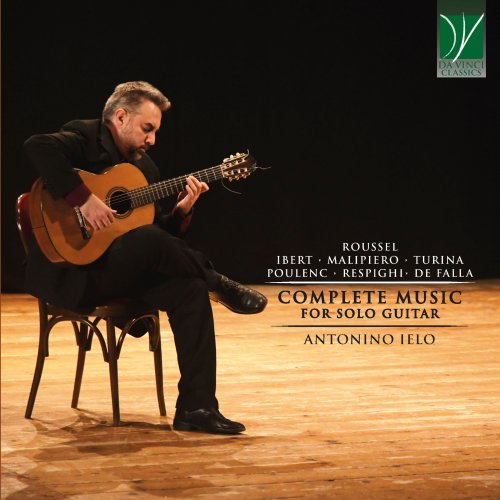

Antonino Ierlo - De Falla, Roussel, Turina, Ibert, Malipiero, Poulenc, Respighi: Complete Music for Solo Guitar (2021)

BAND/ARTIST: Antonino Ierlo

- Title: De Falla, Roussel, Turina, Ibert, Malipiero, Poulenc, Respighi: Complete Music for Solo Guitar

- Year Of Release: 2021

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical Guitar

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 00:51:37

- Total Size: 226 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Homenaje pour Le Tombeau de Debussy

02. Segovia in A Major, Op. 29

03. Fandanguillo, Op. 36

04. Ariette

05. Sonata in D Minor, Op. 61: I. Lento

06. Sonata in D Minor, Op. 61: II. Andante

07. Sonata in D Minor, Op. 61: III. Allegro Vivo

08. Preludio

09. Ráfaga, Op. 53

10. Sarabande pour guitare, FP 179

11. Hommage à Tarrega, Op. 69: Garrotin. Allegretto

12. Hommage à Tarrega, Op. 69: Soleares. Allegro vivo

13. Variazioni

14. Sevillana, Op. 29

Guitarist Antonino Ielo authors his debut album with a collection of solo guitar works from the early 1900s, written by composers from the Mediterranean area, all of whom were non-guitarists. This last detail is non-negligible: when the guitar, in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, established its morphology with six single strings, its repertoire lived for a long time on the exclusive contribution of composers who were, at the same time, pre-eminent virtuosos of this instrument. One should not be surprised, then, that Hector Berlioz, in his Grand Traité d’instrumentation et d’orchestration modernes, stated that it was impossible to write properly for the guitar without being able to play it. The French composer was just sanctioning a matter of fact, establishing an implicit taboo which would be overcome only in the first years of the twentieth century. This album photographs a historical moment – the early twentieth century – in which a series of deeply intertwined phenomena took place. These include the success of Spanish guitarist Andrés Segovia, the arrival of the guitar in the most important concert halls, and, in parallel, the discovery of this instrument by excellent composers who were not guitarist. Many of them, supported by Segovia himself, dismantled Berlioz’s peremptory statement. They thus provided the guitar with a repertoire which was, finally, worthy to compete with those of the other instruments. The appearance of non-guitarists in a field which had hitherto stably remained the property of great virtuosos had an implicit, yet extremely relevant, consequence. Freeing itself from the instrument’s idiomaticity and related sounds, research in the field of guitar opened up towards new harmonic and instrumental horizons; this substantially reshaped the instrument’s aural identity. In the audience’s imagination, the guitar is intimately connected with Spain. The piece which established, more than any other, the intimate connection between the instrument’s cultivated repertoire and the Iberian folk traditions (and from which Ielo ideally starts) is the Homenaje pour le tombeau de Claude Debussy, the only guitar work composed by Manuel de Falla (1876-1946). The Homenaje was written in 1920 for an issue of the celebrated Revue musicale, entirely dedicated to the memory of Debussy. It allows us to appreciate the results of Falla’s systematic study and reflections on the nature of the cante jondo, the most ancestral, mysterious and high expression of Iberian folklore. The writing is pervaded by an unusual, dark and enchanting fascination. We can glimpse Debussy’s ghost, through quotes from La Puerta del vino and La Soirée dans Grenade. More generally, we observe, in Falla’s language, the deep traces left precisely by Debussy and Ravel. The Spanish composer could assimilate them during his seven-years-long stay in Paris (1907-1914). The Homenaje soon entered the repertoire of Segovia and Miguel Llobet; it was a work cherished by the composer, to the point that he created an orchestral version of it, suggestively entitled Elegia de la guitarra (1938). The artistic research of another Iberian composer deeply rooted in his fatherland’s folklore, i.e. Joaquin Turina (1882-1946) was similarly marked by the French taste. Turina, born in Seville, had the possibility of living in the French capital at approximately the same time when his friend Falla was also there. Later, Turina elected Madrid as his definitive residence (1914-1943). Turina’s guitar output, of which Andrés Segovia was the undisputed standard-bearer, is recorded here in its entirety. Upon listening, this output is very coherent. We find here a composer who significantly differs from the one who had debuted with a Quintet for piano and strings, with a late-Romantic style, deeply indebted towards the language of César Franck. Turina’s guitar writing is characterized by a changing mutability, which enlivens the opposition between the Andalusian folklike elements of the cante and of the baile. This dialectical encounter is transformed, in the direction of cultivated music, by his linguistic sensitivity, with an Impressionist mark. The rhapsodic character of Turina’s writing is evident especially in the free forms. These include both the extroverted Sevillana op. 29 (1923) and the ingratiating Fandanguillo op. 36 (1925). Its iridescent style does not renounce the fundamental value of thematic cohesion. In both pieces, in fact, the opening episode is reproposed, almost literally, at the end of the formal arch. This reappearance is prepared, in turn, by a series of quotes of the most characteristic motivic elements of the initial themes, elaborated with a skillful use of chiseling. Another typical feature of Turina’s style is the descriptive and figurative taste, wonderfully exemplified in collections such as the Siluetas op. 70 and the Tarjetas op. 58 for the piano. This taste is resurrected in Ràfaga (1929), a brilliant album leaf: evoking the wind gushes alluded to by its title, it requires notable gifts of power and agility of the performer. The two movements of the later diptych Homenaje a Tàrrega (1932), chronologically the last piece in Turina’s oeuvre, display the extreme emotions of the composer’s expressive world: from the dancing extroversion of Garrotin – an idealized elaboration of the eponymous Flamenco dance – to the dark jondura of Soleares. It is with the Sonata op. 61, written in 1930, that Turina signed his most monumental piece for the guitar. We find here the harmonic and emotional qualities typical of his shorter guitar works, along with his ambition to use the compositional materials cyclically. At the same time, we clearly observe the echoes of a fascinating coeval piano cycle, the Danzas gitanas op. 55 (1929-1930). The first movement (Lento-Allegro) is a Sonata form opened by a violent and theatrical gesture; it brings us into a singular climate of burning grandiloquence. This context melts in the grievous meditation of the slow movement (Andante), whose long melismas allow the Arabian roots of the Iberian folklore to resurface, albeit transfigured. The final Allegro is a tight-knitted rondo; it partly reproposes the musical materials of the first movement, maintaining its elan and dramatic power. The same France which had been, for Falla and Turina, an incredible mine of ideas, was suffused, in the early 1900s, by an incredible cultural liveliness. There operated figures of the standing of Nadia Boulanger, Maurice Ravel and Igor Stravinsky, to say nothing of the composers who belonged, together with Jean Cocteau, in the so-called Groupe des Six (i.e. Georges Auric, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud, Francis Poulenc, Germaine Tailleferre). This was the climate of the country chosen by Andrés Segovia in 1924 in order to seek fortune as a concert musician. Segovia’s stay in Paris would have an immense relevance for the guitar repertoire; it is a chapter of a history that, sooner or later, somebody will have to write. Suffice it to know that the composers who decided to write for the guitar, stimulated by Segovia’s success and bravura, were very numerous. Still, those who survived the Spanish virtuoso’s critical inspection were very few. Among them was Frenchman Albert Roussel (1869-1937), who composed a delightful and self-assured sketch by the title of… Segovia (1925). The deliberately cacophonic and angular harmonizations, built over the bombastic sound of the lower open strings, are a salty caricature of Segovia’s overflowing personality; incidentally, this did not fail to inspire the humorous arrows of still other composers. For example, the case of Darius Milhaud’s Segoviana was famous – but the piece was disdainfully refused by its dedicatee. Even though he was not explicitly bound the personalities of the Six, Frenchman Jacques Ibert (1890-1962), a composer with a solid academic education, wrote music whose carefree and elegantly frivolous traits can be likened precisely to the best results of the Six. The Ariette (1935) found in this programme is a very short character piece. The declared (or rather ostentatious) stylization of Spanish folklore in Ariette lets us glimpse the composer’s histrionic tendency. It counterbalances the deep assimilation of the folkloric traits demonstrated by Falla and Turina’s works.

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) is the last French composer represented in this album. Similar to Auric, Tailleferre and Milhaud, Poulenc left one single piece for solo guitar. His Sarabande was written on the spur of the moment, in March 1960, during a concert tour in the US with soprano Denise Duval. Of the eponymous Baroque dance, this Sarabande reproposes only the slow pace. The inexorable rigour of the Baroque Sarabande’s ternary rhythm cedes the way to a free monologue. Its thematic material is literally derived from an earlier piano work, the Improvisation XIII (1958). If the atmosphere of the piano piece was placidly melancholic, that of the Sarabande assumes a glass-like rarefied connotation. It is a pure distillation of sound, closed by Poulenc with a slow arpeggiation on the six open strings.

Finally, Ielo turns his attention to another musical world, the Italian one. The non-guitarist composers of the Peninsula were, in the first decades of the twentieth century, decidedly less prolific than their colleagues from other nations. However, the cycle of Variazioni written for the guitar by Ottorino Respighi (1879-1936) in the early 1900s problematizes the picture. It is a recently rediscovered work, fortunately found by musicologist Angelo Gilardino among the papers of celebrated guitarist Luigi Mozzani, and saved from an undeserved oblivion. Rather than a real theme with variations, we face a cycle of twelve miniatures. Starting from C major, and following the suite imposed by the circle of the fifths, they review all flat keys. The editor of the printed version created a brief coda which, citing the opening C-major, works as a recapitulation. This work, whose character is generally frowning and austere, is part of Respighi’s non occasional interest in the world of the guitar and of the lute: suffice it to mention the three series of Antiche arie e danze per liuto transcribed for orchestra by the composer respectively in 1917, 1924 and 1932. The series of Italian pieces offered in this broad retrospective gaze is closed by the Preludio written by Gian Francesco Malipiero (1882-1973) in his buen retiro in Asolo (1958). For a curious coincidence, the piece was published, together with Poulenc’s Sarabande, in the Antologia edited by Miguel Abloniz for Ricordi (1961), and which would revolutionize the world of the guitar. Similar to Respighi’s Variazioni, the Preludio is entirely devoid of references to all forms of folklore. It is animated by an implacable motoric power, almost mechanical, which will erupt in the peremptory and cutting chordal conclusion. The broad panorama painted by Antonino Ielo juxtaposes composers very different from each other. Some of them clearly adhere to the world of folklore: someone for an intimate calling (Falla Turina), someone for a subtle ironic will (Ibert); others entirely elude every confrontation with the popular element, drawing desecrating portraits (Roussel), painting architectures with a liminal volumetry (Poulenc) or reaching a music whose beauty is determined by the absence of all extramusical references (Malipiero, Respighi). The specificity of this album, i.e. the main reason for its fascination, is found precisely in this: it individuates the guitar’s new identity in the dialectics between folklore and cultivated elements, and in the continuing transformation of the one into the other.

01. Homenaje pour Le Tombeau de Debussy

02. Segovia in A Major, Op. 29

03. Fandanguillo, Op. 36

04. Ariette

05. Sonata in D Minor, Op. 61: I. Lento

06. Sonata in D Minor, Op. 61: II. Andante

07. Sonata in D Minor, Op. 61: III. Allegro Vivo

08. Preludio

09. Ráfaga, Op. 53

10. Sarabande pour guitare, FP 179

11. Hommage à Tarrega, Op. 69: Garrotin. Allegretto

12. Hommage à Tarrega, Op. 69: Soleares. Allegro vivo

13. Variazioni

14. Sevillana, Op. 29

Guitarist Antonino Ielo authors his debut album with a collection of solo guitar works from the early 1900s, written by composers from the Mediterranean area, all of whom were non-guitarists. This last detail is non-negligible: when the guitar, in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, established its morphology with six single strings, its repertoire lived for a long time on the exclusive contribution of composers who were, at the same time, pre-eminent virtuosos of this instrument. One should not be surprised, then, that Hector Berlioz, in his Grand Traité d’instrumentation et d’orchestration modernes, stated that it was impossible to write properly for the guitar without being able to play it. The French composer was just sanctioning a matter of fact, establishing an implicit taboo which would be overcome only in the first years of the twentieth century. This album photographs a historical moment – the early twentieth century – in which a series of deeply intertwined phenomena took place. These include the success of Spanish guitarist Andrés Segovia, the arrival of the guitar in the most important concert halls, and, in parallel, the discovery of this instrument by excellent composers who were not guitarist. Many of them, supported by Segovia himself, dismantled Berlioz’s peremptory statement. They thus provided the guitar with a repertoire which was, finally, worthy to compete with those of the other instruments. The appearance of non-guitarists in a field which had hitherto stably remained the property of great virtuosos had an implicit, yet extremely relevant, consequence. Freeing itself from the instrument’s idiomaticity and related sounds, research in the field of guitar opened up towards new harmonic and instrumental horizons; this substantially reshaped the instrument’s aural identity. In the audience’s imagination, the guitar is intimately connected with Spain. The piece which established, more than any other, the intimate connection between the instrument’s cultivated repertoire and the Iberian folk traditions (and from which Ielo ideally starts) is the Homenaje pour le tombeau de Claude Debussy, the only guitar work composed by Manuel de Falla (1876-1946). The Homenaje was written in 1920 for an issue of the celebrated Revue musicale, entirely dedicated to the memory of Debussy. It allows us to appreciate the results of Falla’s systematic study and reflections on the nature of the cante jondo, the most ancestral, mysterious and high expression of Iberian folklore. The writing is pervaded by an unusual, dark and enchanting fascination. We can glimpse Debussy’s ghost, through quotes from La Puerta del vino and La Soirée dans Grenade. More generally, we observe, in Falla’s language, the deep traces left precisely by Debussy and Ravel. The Spanish composer could assimilate them during his seven-years-long stay in Paris (1907-1914). The Homenaje soon entered the repertoire of Segovia and Miguel Llobet; it was a work cherished by the composer, to the point that he created an orchestral version of it, suggestively entitled Elegia de la guitarra (1938). The artistic research of another Iberian composer deeply rooted in his fatherland’s folklore, i.e. Joaquin Turina (1882-1946) was similarly marked by the French taste. Turina, born in Seville, had the possibility of living in the French capital at approximately the same time when his friend Falla was also there. Later, Turina elected Madrid as his definitive residence (1914-1943). Turina’s guitar output, of which Andrés Segovia was the undisputed standard-bearer, is recorded here in its entirety. Upon listening, this output is very coherent. We find here a composer who significantly differs from the one who had debuted with a Quintet for piano and strings, with a late-Romantic style, deeply indebted towards the language of César Franck. Turina’s guitar writing is characterized by a changing mutability, which enlivens the opposition between the Andalusian folklike elements of the cante and of the baile. This dialectical encounter is transformed, in the direction of cultivated music, by his linguistic sensitivity, with an Impressionist mark. The rhapsodic character of Turina’s writing is evident especially in the free forms. These include both the extroverted Sevillana op. 29 (1923) and the ingratiating Fandanguillo op. 36 (1925). Its iridescent style does not renounce the fundamental value of thematic cohesion. In both pieces, in fact, the opening episode is reproposed, almost literally, at the end of the formal arch. This reappearance is prepared, in turn, by a series of quotes of the most characteristic motivic elements of the initial themes, elaborated with a skillful use of chiseling. Another typical feature of Turina’s style is the descriptive and figurative taste, wonderfully exemplified in collections such as the Siluetas op. 70 and the Tarjetas op. 58 for the piano. This taste is resurrected in Ràfaga (1929), a brilliant album leaf: evoking the wind gushes alluded to by its title, it requires notable gifts of power and agility of the performer. The two movements of the later diptych Homenaje a Tàrrega (1932), chronologically the last piece in Turina’s oeuvre, display the extreme emotions of the composer’s expressive world: from the dancing extroversion of Garrotin – an idealized elaboration of the eponymous Flamenco dance – to the dark jondura of Soleares. It is with the Sonata op. 61, written in 1930, that Turina signed his most monumental piece for the guitar. We find here the harmonic and emotional qualities typical of his shorter guitar works, along with his ambition to use the compositional materials cyclically. At the same time, we clearly observe the echoes of a fascinating coeval piano cycle, the Danzas gitanas op. 55 (1929-1930). The first movement (Lento-Allegro) is a Sonata form opened by a violent and theatrical gesture; it brings us into a singular climate of burning grandiloquence. This context melts in the grievous meditation of the slow movement (Andante), whose long melismas allow the Arabian roots of the Iberian folklore to resurface, albeit transfigured. The final Allegro is a tight-knitted rondo; it partly reproposes the musical materials of the first movement, maintaining its elan and dramatic power. The same France which had been, for Falla and Turina, an incredible mine of ideas, was suffused, in the early 1900s, by an incredible cultural liveliness. There operated figures of the standing of Nadia Boulanger, Maurice Ravel and Igor Stravinsky, to say nothing of the composers who belonged, together with Jean Cocteau, in the so-called Groupe des Six (i.e. Georges Auric, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud, Francis Poulenc, Germaine Tailleferre). This was the climate of the country chosen by Andrés Segovia in 1924 in order to seek fortune as a concert musician. Segovia’s stay in Paris would have an immense relevance for the guitar repertoire; it is a chapter of a history that, sooner or later, somebody will have to write. Suffice it to know that the composers who decided to write for the guitar, stimulated by Segovia’s success and bravura, were very numerous. Still, those who survived the Spanish virtuoso’s critical inspection were very few. Among them was Frenchman Albert Roussel (1869-1937), who composed a delightful and self-assured sketch by the title of… Segovia (1925). The deliberately cacophonic and angular harmonizations, built over the bombastic sound of the lower open strings, are a salty caricature of Segovia’s overflowing personality; incidentally, this did not fail to inspire the humorous arrows of still other composers. For example, the case of Darius Milhaud’s Segoviana was famous – but the piece was disdainfully refused by its dedicatee. Even though he was not explicitly bound the personalities of the Six, Frenchman Jacques Ibert (1890-1962), a composer with a solid academic education, wrote music whose carefree and elegantly frivolous traits can be likened precisely to the best results of the Six. The Ariette (1935) found in this programme is a very short character piece. The declared (or rather ostentatious) stylization of Spanish folklore in Ariette lets us glimpse the composer’s histrionic tendency. It counterbalances the deep assimilation of the folkloric traits demonstrated by Falla and Turina’s works.

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) is the last French composer represented in this album. Similar to Auric, Tailleferre and Milhaud, Poulenc left one single piece for solo guitar. His Sarabande was written on the spur of the moment, in March 1960, during a concert tour in the US with soprano Denise Duval. Of the eponymous Baroque dance, this Sarabande reproposes only the slow pace. The inexorable rigour of the Baroque Sarabande’s ternary rhythm cedes the way to a free monologue. Its thematic material is literally derived from an earlier piano work, the Improvisation XIII (1958). If the atmosphere of the piano piece was placidly melancholic, that of the Sarabande assumes a glass-like rarefied connotation. It is a pure distillation of sound, closed by Poulenc with a slow arpeggiation on the six open strings.

Finally, Ielo turns his attention to another musical world, the Italian one. The non-guitarist composers of the Peninsula were, in the first decades of the twentieth century, decidedly less prolific than their colleagues from other nations. However, the cycle of Variazioni written for the guitar by Ottorino Respighi (1879-1936) in the early 1900s problematizes the picture. It is a recently rediscovered work, fortunately found by musicologist Angelo Gilardino among the papers of celebrated guitarist Luigi Mozzani, and saved from an undeserved oblivion. Rather than a real theme with variations, we face a cycle of twelve miniatures. Starting from C major, and following the suite imposed by the circle of the fifths, they review all flat keys. The editor of the printed version created a brief coda which, citing the opening C-major, works as a recapitulation. This work, whose character is generally frowning and austere, is part of Respighi’s non occasional interest in the world of the guitar and of the lute: suffice it to mention the three series of Antiche arie e danze per liuto transcribed for orchestra by the composer respectively in 1917, 1924 and 1932. The series of Italian pieces offered in this broad retrospective gaze is closed by the Preludio written by Gian Francesco Malipiero (1882-1973) in his buen retiro in Asolo (1958). For a curious coincidence, the piece was published, together with Poulenc’s Sarabande, in the Antologia edited by Miguel Abloniz for Ricordi (1961), and which would revolutionize the world of the guitar. Similar to Respighi’s Variazioni, the Preludio is entirely devoid of references to all forms of folklore. It is animated by an implacable motoric power, almost mechanical, which will erupt in the peremptory and cutting chordal conclusion. The broad panorama painted by Antonino Ielo juxtaposes composers very different from each other. Some of them clearly adhere to the world of folklore: someone for an intimate calling (Falla Turina), someone for a subtle ironic will (Ibert); others entirely elude every confrontation with the popular element, drawing desecrating portraits (Roussel), painting architectures with a liminal volumetry (Poulenc) or reaching a music whose beauty is determined by the absence of all extramusical references (Malipiero, Respighi). The specificity of this album, i.e. the main reason for its fascination, is found precisely in this: it individuates the guitar’s new identity in the dialectics between folklore and cultivated elements, and in the continuing transformation of the one into the other.

Year 2021 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads