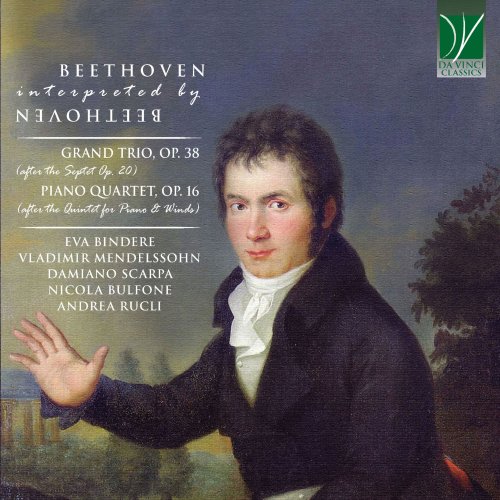

Various Artists - Beethoven Interpreted by Beethoven (2021)

BAND/ARTIST: Various Artists

- Title: Beethoven Interpreted by Beethoven

- Year Of Release: 2021

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 47:02 min

- Total Size: 271 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

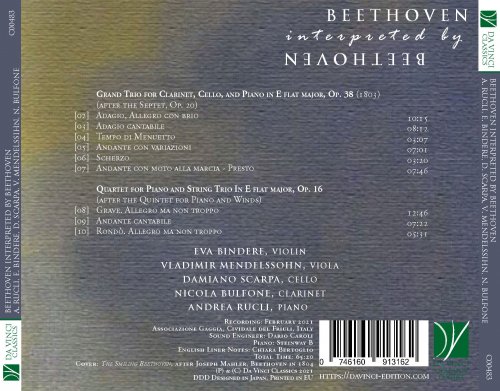

Tracklist:

1. Piano Trio No. 8 in E-Flat Major, Op. 38: I. Adagio, Allegro con brio

2. Piano Trio No. 8 in E-Flat Major, Op. 38: II. Adagio cantabile

3. Piano Trio No. 8 in E-Flat Major, Op. 38: III. Tempo di Menuetto

4. Piano Trio No. 8 in E-Flat Major, Op. 38: IV. Andante con variazioni

5. Piano Trio No. 8 in E-Flat Major, Op. 38: V. Scherzo

6. Piano Trio No. 8 in E-Flat Major, Op. 38: VI. Andante con moto alla marcia : Presto

7. Quartet for Piano and String Trio in E-Flat Major, Op. 16: I. Grave. Allegro ma non troppo (After the Quintet for Piano and Winds)

8. Quartet for Piano and String Trio in E-Flat Major, Op. 16: II. Andante cantabile (After the Quintet for Piano and Winds)

9. Quartet for Piano and String Trio in E-Flat Major, Op. 16: III. Rondò. Allegro ma non troppo (After the Quintet for Piano and Winds)

It sometimes happens with the musical repertoire as it happens – if such a comparison is allowed – with female hair. Typically, ladies with curly hair would like it straight, and viceversa. The repertoire written for other instruments than that one plays seems always more attractive than the repertoire originally written for that instrument. So the temptation of transcriptions is always at hand. Through the art of transcription, it is possible to realize more or less satisfactory versions of virtually every piece for virtually every instrument or ensemble. Still, the artistic quality of the result depends largely on the actual adaptability of the original piece, on the typical features of the instrumental media, and on the transcriber’ skill. There are transcriptions which easily compete with the original version, and sometimes possess a beauty of their own which the original did not have. There are transcriptions in which the effort is so extreme that the result is strained and unnatural. Sometimes, unconvincing results are determined by – paradoxically – an excess of respect for the original text. Transcribing is akin to translating, and the Italians say traduttore traditore, “translators are traitors”. Excessive respect for the letter (the “notes”) of the original piece may produce a “spiritually” unfaithful result, meaning that the musical value of the transcription is limited by the incompatibility between the original concept and the transcribed media. Still, there are limits to what a transcriber may change in the original without betraying it to the point of unrecognizability.

These limits, however, may easily be overcome when the transcription is authored by the composer of the original version himself. In this case – as in the case of a polyglot translating his or her own writings – the author knows what is essential to the work’s identity and what may be changed in order to achieve more satisfactory results in the transcribed version. The case is not infrequent, therefore, of pieces written in two or more versions by the composer, each possessing an inherent worth of its own.

Even in the most successful cases, however, the question arises sharply: is then timbre (i.e. the typical aural quality of a particular instrument) so expendable a component of a musical work that it can be so easily sacrificed? And, furthermore: did the composer disregard the particular idiosyncrasies and idiomatic musical gestures of an instrument when writing for it in the first place? Is the violin pizzicato fully replaceable with a flute staccato, to use a very trivial example?

This question becomes pressing when the original works seem perfectly suited for a particular instrument or ensemble, and to renounce its particular features seems akin to sacrificing a fundamental component of its beauty. Occasionally, the listener wonders whether the choice to transcribe was really due to cogent artistic inspirations, or rather to the “mere” wish to increase a work’s dissemination and the sales of its scores.

This question spontaneously surfaces in the case of Beethoven’s op. 16. The first edition of the piece, published in 1801 by Mollo in Vienna, bears an elaborate and somewhat confusing title: “GRAND QUINTETTO | pour le | Forte-Piano | avec Oboë, Clarinette, Basson et Cor | oû | Violon Alto, et Violoncelle”. Seemingly, then, the version for piano quartet was not even a transcription proper, but rather an equally viable version on a par with that for quintet. Significantly, moreover, the parts for both the winds and the strings were included with that of the piano. Still, the piece is called Quintetto, thus attributing – at least under this viewpoint – a slight primacy to the quintet version. The same applies to the reprint which followed suit, the next year, published by Simrock; here too the two versions are equally acceptable, but the title is Quintetto.

That the Quintet might be considered as “more original” (to paraphrase George Orwell’s Animal Farm) is also suggested by the fact that the piece bears an undeniable resemblance with Mozart’s Piano Quintet. Beethoven’s work (in its version with winds) shares with Mozart’s model the same key, the same instruments of destination, and a very similar structure, which also includes elements of a common language to which the young Beethoven was still attached.

As has been pointed out, however, there are also substantial differences between the two works. These regard firstly the stages of life and career in which the two composers were at the moment of the pieces’ creation. Mozart was at the peak of his creative powers, had crafted his own particular style in its finest details, and was acclaimed for the excellency he had achieved in all musical genres. Beethoven was still in a developmental stage; most of his greatest masterpieces were still to come and he was not yet in the Gotha of Viennese music. It is surmisable, therefore, that his deliberate homage to Mozart was also a declaration of intentions, perhaps corresponding to the famous prophecy according to which he was to receive Mozart’s spirit from Haydn’s hands. Both Beethoven and Mozart, moreover, were acclaimed as keyboard players; in Beethoven’s case, he was possibly more admired for his performative skills than for his compositional output. The young virtuoso’s brilliancy and desire to demonstrate his ability are abundantly displayed in the challenging piano writing of the Quintet/Quartet, having unmistakably concertante features.

The key of E-flat, which was so crucial for both Mozart and for Beethoven (from the Eroica to the Emperor Concerto) shines in both its luminous and its melancholic features; the beautiful lyricism of the singing passages, particularly in the Andante cantabile, offers to every performer the possibility of entering a dialogue of intense affectivity.

The concertante style is particularly evident in the Cadenza performed by the piano. Reportedly, at the piece’s premiere, in 1797, Beethoven amused himself by extending the Cadenza with improvised figurations. His fellow performers (among whom the celebrated oboist Ramm, who was a recognized authority in the field) were constantly ready to reassume their playing, and brought their instruments to their mouths countless times whilst Beethoven feigned a correspondingly high number of conclusions. Assuredly, the players were not flattered by the show, and manifested their disappointment in a rather evident fashion.

The enigma concerning the instrumental destination of the work, therefore, is increased rather than diminished by the correspondence with Mozart’s Piano Quintet. If Beethoven was purposefully alluding to his elder colleague’s model, including in what concerns the instrumental choices, why then did he create another version? But, on the other hand, it is equally true that the version with string trio sounds beautifully, even if it loosens the tie with Mozart’s work. And this is not perforce a minus: rather, when deprived of the excessively evident allusion to Mozart, Beethoven’s own style shines more clearly and reveals, as a promise, the results to which his own genius would bring the musical art.

Similar questions apply to the Trio op. 38, deriving from his Septet op. 20, composed slightly later than the preceding work (between 1799 and 1800). In this case, however, there is a clear chronological difference between the two versions realized by the composer, since the Trio version followed the Septet after approximately three years.

The Septet had represented a true landmark in Beethoven’s career; it had attracted the critics’ and the audience’s attention on the young composer, and would remain one of his most successful composition throughout his lifetime – to his later chagrin, since in his maturity he came to see the work’s limits and to deplore the attention it still enjoyed.

Transforming a piece for seven players into one for three implies a substantial adaptation (more substantial than that found in the passage from five to four). Many of the Septet’s parts converge in that of the piano in the Trio version, particularly as concerns what was originally assigned to the strings, whilst the Trio’s cello part incorporates the original cello part and excerpts from those of the bassoon and horn.

The Trio version was dedicated by Beethoven to his medical doctor, who was a good violin player and whose daughter was an amateur pianist. The adaptation, therefore, was evidently conceived as a homage to their musical evenings, as affirmed by the composer himself in the dedicatory letter, printed in the published version. Written in French, the letter claims that the dedicatee’s fame and the friendship between Beethoven and him should have encouraged Beethoven to dedicate a more substantial piece to him. However, Beethoven decided to create this arrangement considering the “ease of performance” and the aim of providing a satisfactory work for the “amiable circle” of the doctor’s family.

Together, these two works and their transcriptions constitute a fascinating CD programme. On the one hand, their chronological closeness affords us a view on the young Beethoven’s style and personality, at a time when his outlook on life was still optimistic and joyful, good-humoured, good-natured and ironic. On the other, they show that masterful transcriptions represent not only “another version” of an original, but rather a new perspective, a refreshing light which can illuminate their beauty in innovative ways. Furthermore, they provide us with a glimpse on the practices of chamber music playing, which used to represent a fundamental moment of sociability, artistry and mutual enjoyment.

Liner Notes © Chiara Bertoglio

These limits, however, may easily be overcome when the transcription is authored by the composer of the original version himself. In this case – as in the case of a polyglot translating his or her own writings – the author knows what is essential to the work’s identity and what may be changed in order to achieve more satisfactory results in the transcribed version. The case is not infrequent, therefore, of pieces written in two or more versions by the composer, each possessing an inherent worth of its own.

Even in the most successful cases, however, the question arises sharply: is then timbre (i.e. the typical aural quality of a particular instrument) so expendable a component of a musical work that it can be so easily sacrificed? And, furthermore: did the composer disregard the particular idiosyncrasies and idiomatic musical gestures of an instrument when writing for it in the first place? Is the violin pizzicato fully replaceable with a flute staccato, to use a very trivial example?

This question becomes pressing when the original works seem perfectly suited for a particular instrument or ensemble, and to renounce its particular features seems akin to sacrificing a fundamental component of its beauty. Occasionally, the listener wonders whether the choice to transcribe was really due to cogent artistic inspirations, or rather to the “mere” wish to increase a work’s dissemination and the sales of its scores.

This question spontaneously surfaces in the case of Beethoven’s op. 16. The first edition of the piece, published in 1801 by Mollo in Vienna, bears an elaborate and somewhat confusing title: “GRAND QUINTETTO | pour le | Forte-Piano | avec Oboë, Clarinette, Basson et Cor | oû | Violon Alto, et Violoncelle”. Seemingly, then, the version for piano quartet was not even a transcription proper, but rather an equally viable version on a par with that for quintet. Significantly, moreover, the parts for both the winds and the strings were included with that of the piano. Still, the piece is called Quintetto, thus attributing – at least under this viewpoint – a slight primacy to the quintet version. The same applies to the reprint which followed suit, the next year, published by Simrock; here too the two versions are equally acceptable, but the title is Quintetto.

That the Quintet might be considered as “more original” (to paraphrase George Orwell’s Animal Farm) is also suggested by the fact that the piece bears an undeniable resemblance with Mozart’s Piano Quintet. Beethoven’s work (in its version with winds) shares with Mozart’s model the same key, the same instruments of destination, and a very similar structure, which also includes elements of a common language to which the young Beethoven was still attached.

As has been pointed out, however, there are also substantial differences between the two works. These regard firstly the stages of life and career in which the two composers were at the moment of the pieces’ creation. Mozart was at the peak of his creative powers, had crafted his own particular style in its finest details, and was acclaimed for the excellency he had achieved in all musical genres. Beethoven was still in a developmental stage; most of his greatest masterpieces were still to come and he was not yet in the Gotha of Viennese music. It is surmisable, therefore, that his deliberate homage to Mozart was also a declaration of intentions, perhaps corresponding to the famous prophecy according to which he was to receive Mozart’s spirit from Haydn’s hands. Both Beethoven and Mozart, moreover, were acclaimed as keyboard players; in Beethoven’s case, he was possibly more admired for his performative skills than for his compositional output. The young virtuoso’s brilliancy and desire to demonstrate his ability are abundantly displayed in the challenging piano writing of the Quintet/Quartet, having unmistakably concertante features.

The key of E-flat, which was so crucial for both Mozart and for Beethoven (from the Eroica to the Emperor Concerto) shines in both its luminous and its melancholic features; the beautiful lyricism of the singing passages, particularly in the Andante cantabile, offers to every performer the possibility of entering a dialogue of intense affectivity.

The concertante style is particularly evident in the Cadenza performed by the piano. Reportedly, at the piece’s premiere, in 1797, Beethoven amused himself by extending the Cadenza with improvised figurations. His fellow performers (among whom the celebrated oboist Ramm, who was a recognized authority in the field) were constantly ready to reassume their playing, and brought their instruments to their mouths countless times whilst Beethoven feigned a correspondingly high number of conclusions. Assuredly, the players were not flattered by the show, and manifested their disappointment in a rather evident fashion.

The enigma concerning the instrumental destination of the work, therefore, is increased rather than diminished by the correspondence with Mozart’s Piano Quintet. If Beethoven was purposefully alluding to his elder colleague’s model, including in what concerns the instrumental choices, why then did he create another version? But, on the other hand, it is equally true that the version with string trio sounds beautifully, even if it loosens the tie with Mozart’s work. And this is not perforce a minus: rather, when deprived of the excessively evident allusion to Mozart, Beethoven’s own style shines more clearly and reveals, as a promise, the results to which his own genius would bring the musical art.

Similar questions apply to the Trio op. 38, deriving from his Septet op. 20, composed slightly later than the preceding work (between 1799 and 1800). In this case, however, there is a clear chronological difference between the two versions realized by the composer, since the Trio version followed the Septet after approximately three years.

The Septet had represented a true landmark in Beethoven’s career; it had attracted the critics’ and the audience’s attention on the young composer, and would remain one of his most successful composition throughout his lifetime – to his later chagrin, since in his maturity he came to see the work’s limits and to deplore the attention it still enjoyed.

Transforming a piece for seven players into one for three implies a substantial adaptation (more substantial than that found in the passage from five to four). Many of the Septet’s parts converge in that of the piano in the Trio version, particularly as concerns what was originally assigned to the strings, whilst the Trio’s cello part incorporates the original cello part and excerpts from those of the bassoon and horn.

The Trio version was dedicated by Beethoven to his medical doctor, who was a good violin player and whose daughter was an amateur pianist. The adaptation, therefore, was evidently conceived as a homage to their musical evenings, as affirmed by the composer himself in the dedicatory letter, printed in the published version. Written in French, the letter claims that the dedicatee’s fame and the friendship between Beethoven and him should have encouraged Beethoven to dedicate a more substantial piece to him. However, Beethoven decided to create this arrangement considering the “ease of performance” and the aim of providing a satisfactory work for the “amiable circle” of the doctor’s family.

Together, these two works and their transcriptions constitute a fascinating CD programme. On the one hand, their chronological closeness affords us a view on the young Beethoven’s style and personality, at a time when his outlook on life was still optimistic and joyful, good-humoured, good-natured and ironic. On the other, they show that masterful transcriptions represent not only “another version” of an original, but rather a new perspective, a refreshing light which can illuminate their beauty in innovative ways. Furthermore, they provide us with a glimpse on the practices of chamber music playing, which used to represent a fundamental moment of sociability, artistry and mutual enjoyment.

Liner Notes © Chiara Bertoglio

Year 2021 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads