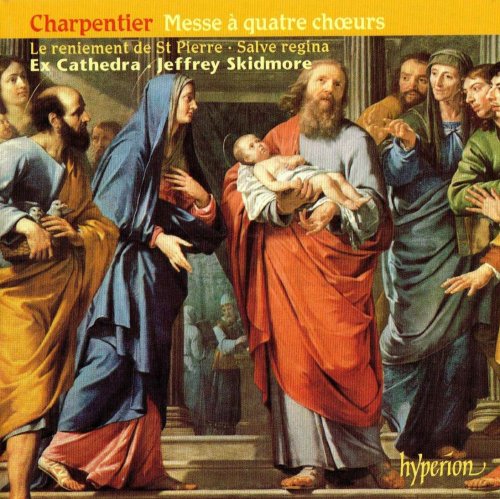

Ex Cathedra, Jeffrey Skidmore - Charpentier: Messe à quatre chœurs (2004)

BAND/ARTIST: Ex Cathedra, Jeffrey Skidmore

- Title: Charpentier: Messe à quatre chœurs

- Year Of Release: 2004

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical, Sacred

- Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

- Total Time: 01:11:57

- Total Size: 314 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

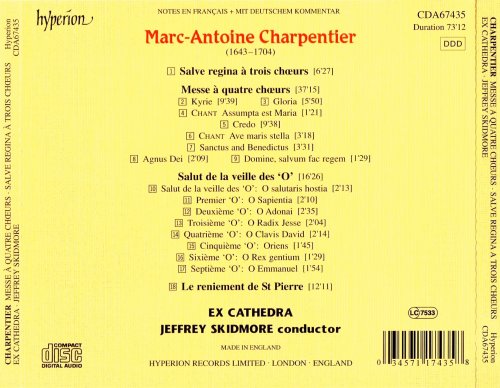

Tracklist:

1 Salve Regina A Trois Chœurs 6:27

Messe A Quatre Chœurs (37:15)

2 Kyrie

3 Gloria

4 Chant: Assumpta Est Maria

Composed By – G. G. Nivers

5 Credo

6 Chant: Ave Maris Stella

Composed By – G. G. Nivers

7 Sanctus & Benedictus

8 Agnus Dei

9 Domine, Salvum Fac Regem

Salut de la Veille Des 'O' (16:26)

10 Salut de la Veille Des 'O': O Salutaris Hostia

11 Premier 'O': O Sapientia

12 Deuxième 'O': O Adonai

13 Troisième 'O': O Radix Jesse

14 Quatrième 'O': O Clavis David

15 Cinquième 'O': O Oriens

16 Sixième 'O': O Rex Gentium

17 Septième 'O': O Emmanuel

18 La Reniement de St Pierre 12:11

1 Salve Regina A Trois Chœurs 6:27

Messe A Quatre Chœurs (37:15)

2 Kyrie

3 Gloria

4 Chant: Assumpta Est Maria

Composed By – G. G. Nivers

5 Credo

6 Chant: Ave Maris Stella

Composed By – G. G. Nivers

7 Sanctus & Benedictus

8 Agnus Dei

9 Domine, Salvum Fac Regem

Salut de la Veille Des 'O' (16:26)

10 Salut de la Veille Des 'O': O Salutaris Hostia

11 Premier 'O': O Sapientia

12 Deuxième 'O': O Adonai

13 Troisième 'O': O Radix Jesse

14 Quatrième 'O': O Clavis David

15 Cinquième 'O': O Oriens

16 Sixième 'O': O Rex Gentium

17 Septième 'O': O Emmanuel

18 La Reniement de St Pierre 12:11

Within a few years of his death, Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s music had largely disappeared into oblivion. This is in striking contrast to that of such contemporaries as Lully and Lalande, which stayed in the repertory for up to a century and reflects the fact that they were employed at Louis XIV’s court while Charpentier remained something of an outsider. Indeed, the Charpentier revival has occurred only quite recently, but has steadily gathered momentum over the last few decades in a fruitful collaboration between performers and scholars. The present disc represents a significant addition to this exploration of the music of ‘one of the most excellent composers France has ever known’ (Journal de Trévoux, August 1709).

Although hard facts about Charpentier’s life are scarce, we do know that in his twenties he spent some time in Rome, probably during the period 1665/6 to 1669. During his stay there he ‘studied music … under Carissimi, the most esteemed composer in Italy’ (Mercure Galant, March 1688). Charpentier would certainly have become immersed in the long-established Italian polychoral tradition, and it was surely this experience that inspired his own works for multiple choirs. As well as numerous pieces for two choirs, his output includes one for three, the Salve regina à trois chœurs, and one for four, the Messe à quatre chœurs, both of which feature on the present disc.

Mass composition in late seventeenth-century France remained conservative; composers deliberately avoided the same modern features that they were by now using in the motet. Furthermore, Louis XIV’s personal dislike of sung Mass meant that composers working at the royal court did not need to write Masses at all. In this context, Charpentier’s eleven Masses are quite exceptional. They not only employ an up-to-date musical style but between them illustrate Charpentier’s own mantra that ‘diversity alone makes for all that is perfect’. For instance, alongside the well known Messe de minuit, which incorporates traditional French noël tunes, we find a Mass for women’s voices only (for the nuns of the convent Port-Royal), one for instruments alone, and the Messe à quatre chœurs, the distinguishing feature of which is clear from its title.

As with most of Charpentier’s output, the precise date of composition of this work is unknown. Its position in the composer’s autograph manuscripts suggests that it was an early work and thus probably written not long after his return from Italy, or even while he was still there. Patricia Ranum has suggested that it could have been performed at ceremonies in Paris in August or December 1672. A posthumous inventory of Charpentier’s works makes reference to a sixteen-voice Mass which he apparently composed in Rome for ‘les mariniers’. Whether this refers to the present work is not certain; it may instead be a reference to a four-choir Mass by the Italian composer Francesco Beretta, Missa Mirabiles elationes maris, an annotated copy of which survives in Charpentier’s hand. This could have been the model for his Messe à quatre chœurs, though the fact that the two works are very different in their handling of the choirs makes this seem less likely. Still, Charpentier’s interest in Beretta’s score underlines his interest and immersion in the Italian polychoral Mass tradition.

Having four choirs at his disposal gives Charpentier scope for considerable variety of scoring and texture. Not only does he use his choral groups both antiphonally and in combination, but he also incorporates passages for various different ensembles of solo voices. Particularly striking in this respect is the opening of the Gloria. In this highly melismatic setting of the text ‘Gloria in excelsis Deo’ for four solo sopranos (one from each choir, and therefore physically separated), it is not difficult to imagine that the composer had a choir of heavenly angels in mind. All four choirs then enter together, with a stately, homophonic setting of the text ‘et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis’ before declaiming in turn the word ‘pax’ on long notes, creating an appropriately peaceful setting. The music becomes immediately more lively at ‘Laudamus te’ as the joyous phrases ‘We praise thee. We bless thee. We worship thee. We glorify thee’ are passed between the choirs. Such contrasts of scoring, texture and musical material occur throughout the Mass and not only sustain the musical interest but also clearly serve to enhance the liturgical text.

On a number of occasions in his score, Charpentier indicates that the organist should improvise between sections; indeed, it was common practice at the time to incorporate short organ pieces into the Mass in this way. What is unusual here is that during the improvisations before and after the second Kyrie, Charpentier may have intended his singers to move away from their original positions and back again: two small diagrams on the first page of the score appear to show two different arrangements of the choirs in relation to the altar. On this recording the organ interpolations are imaginatively improvised by David Ponsford in the style of Charpentier’s contemporary Nicolas Lebègue, an organist at the royal chapel whose Pièces d’orgue were published in 1676 (and therefore relatively close in date to the Mass itself). These improvisations also draw on the same genres and associated registrations that are found in the French organ Mass of the period (for example, plein jeu, fugue, menuet-trio and canarie-gigue).

Also incorporated between movements of the Mass are two pieces of plainsong by the organist, composer and theorist Guillaume Gabriel Nivers (c1632–1714). This is not Gregorian chant but rather what was known as plainchant musical, a new type of plainsong created in France in the early seventeenth century and characterized by simple, mainly syllabic melodies. Nivers wrote two instruction manuals on the new plainsong which established guidelines for its performance, including advice on ornamentation.

The Mass concludes with a setting of the psalm text ‘Domine, salvum fac regem’ (‘O Lord, save the king’). The convention of ending Mass with this prayer for the king’s health had begun in the early seventeenth century during the reign of Louis XIII. Despite the fact that Charpentier spent his life largely outside court circles, the inclusion of a Domine, salvum setting as an integral part of many of his Masses clearly points to the climate of absolutism in late seventeenth-century France.

In the Salve regina à trois chœurs, the third choir is treated differently from the other two. Whereas they are in four parts, this is in three parts only. Moreover, it enters only at the second section and is consistently labelled ‘exules’ (‘exiles’). These factors, together with the soloistic nature of the individual lines, support the idea that this ‘choir’ was a trio of soloists. The term ‘exules’ might further suggest that it was spatially separated from the others. The work falls into three sections. The first is characterized by a clear reference to the Salve regina plainsong in the opening vocal entries. In the second, Charpentier graphically paints the emotive text; at the reference to ‘this valley of tears’ there is a chromatic descent in all parts resulting in strikingly dissonant harmonies. It was surely such expressive harmony that inspired Serré de Rieux to comment (1734) that ‘ninths and tritones sparkled in [Charpentier’s] hands’. Towards the end of the Salve regina, repetitions of the apostrophe ‘O’ are grouped in threes and scored in turn for the whole ensemble, then the first choir, and finally the ‘exiles’, producing a double-echo effect.

Settings of the exclamation ‘O’ are a prominent feature of Salut de la veille des ‘O’. In a tradition dating back to eighth-century France, these seven antiphons would have been performed before and after the Magnificat at Vespers during the week before Christmas. In Charpentier’s cycle, probably dating from the early 1690s, these are preceded by a setting of ‘O salutaris hostia’, also included here. The texts of the seven antiphons implore God to come to earth and save his people. The first letter of each word following the ‘O’ form a reverse acrostic, spelling ERO CRAS (‘I will be tomorrow’), a response from God to his Church’s prayers. Four of the antiphons (and ‘O salutaris’) are scored for an ensemble of haute-contre (high tenor), tenor and bass voices and continuo. The sixth ‘O’ is scored for a solo haute-contre, two obbligato violins and continuo. Interestingly, Charpentier labels the vocal line ‘Mr Chopelet’, a singer known to be associated with the Paris Opéra. Given that Opéra singers regularly sang at the Jesuit church of Saint-Louis, where Charpentier was employed between 1688 and 1698, this annotation strengthens the possibility that the Jesuits commissioned this set of pieces. The two remaining antiphons (four and five) are scored for a four-part choir and orchestra. These both make use of expressive harmonies at the text ‘sedentem / sedentes in tenebris et umbra mortis’ (‘sitting / who sit in the darkness and in shadow of death’).

The motet Le reniement de St Pierre is a dramatic account of Peter’s denial of Christ, its text skilfully incorporating material from accounts of the Passion in all four Gospels. Sébastien de Brossard, composer, theorist and bibliophile, described it as ‘an oratorio in the Italian style’. Charpentier’s forces are relatively modest, involving only voices and continuo. Nevertheless, he takes every opportunity to intensify the text. Just before the cock crows, for instance, there is a quartet in which Peter vehemently denies knowing Jesus. Charpentier’s agitated music perfectly captures both Peter’s adamance and the persistent questions and accusations of the other three characters. Perhaps the most memorable passage in the work, though, is the final section. Over thirty bars long, this is built entirely on a setting of the words ‘flevit amare’ (‘wept bitterly’). Here the vocal lines weave a dense web of counterpoint, full of suspensions and other expressive dissonances. This powerful evocation of Peter’s remorse is reminiscent of the final chorus of lament in Carissimi’s Jephte; Charpentier clearly knew this work very well, since he himself made a copy of his teacher’s masterpiece.

Although hard facts about Charpentier’s life are scarce, we do know that in his twenties he spent some time in Rome, probably during the period 1665/6 to 1669. During his stay there he ‘studied music … under Carissimi, the most esteemed composer in Italy’ (Mercure Galant, March 1688). Charpentier would certainly have become immersed in the long-established Italian polychoral tradition, and it was surely this experience that inspired his own works for multiple choirs. As well as numerous pieces for two choirs, his output includes one for three, the Salve regina à trois chœurs, and one for four, the Messe à quatre chœurs, both of which feature on the present disc.

Mass composition in late seventeenth-century France remained conservative; composers deliberately avoided the same modern features that they were by now using in the motet. Furthermore, Louis XIV’s personal dislike of sung Mass meant that composers working at the royal court did not need to write Masses at all. In this context, Charpentier’s eleven Masses are quite exceptional. They not only employ an up-to-date musical style but between them illustrate Charpentier’s own mantra that ‘diversity alone makes for all that is perfect’. For instance, alongside the well known Messe de minuit, which incorporates traditional French noël tunes, we find a Mass for women’s voices only (for the nuns of the convent Port-Royal), one for instruments alone, and the Messe à quatre chœurs, the distinguishing feature of which is clear from its title.

As with most of Charpentier’s output, the precise date of composition of this work is unknown. Its position in the composer’s autograph manuscripts suggests that it was an early work and thus probably written not long after his return from Italy, or even while he was still there. Patricia Ranum has suggested that it could have been performed at ceremonies in Paris in August or December 1672. A posthumous inventory of Charpentier’s works makes reference to a sixteen-voice Mass which he apparently composed in Rome for ‘les mariniers’. Whether this refers to the present work is not certain; it may instead be a reference to a four-choir Mass by the Italian composer Francesco Beretta, Missa Mirabiles elationes maris, an annotated copy of which survives in Charpentier’s hand. This could have been the model for his Messe à quatre chœurs, though the fact that the two works are very different in their handling of the choirs makes this seem less likely. Still, Charpentier’s interest in Beretta’s score underlines his interest and immersion in the Italian polychoral Mass tradition.

Having four choirs at his disposal gives Charpentier scope for considerable variety of scoring and texture. Not only does he use his choral groups both antiphonally and in combination, but he also incorporates passages for various different ensembles of solo voices. Particularly striking in this respect is the opening of the Gloria. In this highly melismatic setting of the text ‘Gloria in excelsis Deo’ for four solo sopranos (one from each choir, and therefore physically separated), it is not difficult to imagine that the composer had a choir of heavenly angels in mind. All four choirs then enter together, with a stately, homophonic setting of the text ‘et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis’ before declaiming in turn the word ‘pax’ on long notes, creating an appropriately peaceful setting. The music becomes immediately more lively at ‘Laudamus te’ as the joyous phrases ‘We praise thee. We bless thee. We worship thee. We glorify thee’ are passed between the choirs. Such contrasts of scoring, texture and musical material occur throughout the Mass and not only sustain the musical interest but also clearly serve to enhance the liturgical text.

On a number of occasions in his score, Charpentier indicates that the organist should improvise between sections; indeed, it was common practice at the time to incorporate short organ pieces into the Mass in this way. What is unusual here is that during the improvisations before and after the second Kyrie, Charpentier may have intended his singers to move away from their original positions and back again: two small diagrams on the first page of the score appear to show two different arrangements of the choirs in relation to the altar. On this recording the organ interpolations are imaginatively improvised by David Ponsford in the style of Charpentier’s contemporary Nicolas Lebègue, an organist at the royal chapel whose Pièces d’orgue were published in 1676 (and therefore relatively close in date to the Mass itself). These improvisations also draw on the same genres and associated registrations that are found in the French organ Mass of the period (for example, plein jeu, fugue, menuet-trio and canarie-gigue).

Also incorporated between movements of the Mass are two pieces of plainsong by the organist, composer and theorist Guillaume Gabriel Nivers (c1632–1714). This is not Gregorian chant but rather what was known as plainchant musical, a new type of plainsong created in France in the early seventeenth century and characterized by simple, mainly syllabic melodies. Nivers wrote two instruction manuals on the new plainsong which established guidelines for its performance, including advice on ornamentation.

The Mass concludes with a setting of the psalm text ‘Domine, salvum fac regem’ (‘O Lord, save the king’). The convention of ending Mass with this prayer for the king’s health had begun in the early seventeenth century during the reign of Louis XIII. Despite the fact that Charpentier spent his life largely outside court circles, the inclusion of a Domine, salvum setting as an integral part of many of his Masses clearly points to the climate of absolutism in late seventeenth-century France.

In the Salve regina à trois chœurs, the third choir is treated differently from the other two. Whereas they are in four parts, this is in three parts only. Moreover, it enters only at the second section and is consistently labelled ‘exules’ (‘exiles’). These factors, together with the soloistic nature of the individual lines, support the idea that this ‘choir’ was a trio of soloists. The term ‘exules’ might further suggest that it was spatially separated from the others. The work falls into three sections. The first is characterized by a clear reference to the Salve regina plainsong in the opening vocal entries. In the second, Charpentier graphically paints the emotive text; at the reference to ‘this valley of tears’ there is a chromatic descent in all parts resulting in strikingly dissonant harmonies. It was surely such expressive harmony that inspired Serré de Rieux to comment (1734) that ‘ninths and tritones sparkled in [Charpentier’s] hands’. Towards the end of the Salve regina, repetitions of the apostrophe ‘O’ are grouped in threes and scored in turn for the whole ensemble, then the first choir, and finally the ‘exiles’, producing a double-echo effect.

Settings of the exclamation ‘O’ are a prominent feature of Salut de la veille des ‘O’. In a tradition dating back to eighth-century France, these seven antiphons would have been performed before and after the Magnificat at Vespers during the week before Christmas. In Charpentier’s cycle, probably dating from the early 1690s, these are preceded by a setting of ‘O salutaris hostia’, also included here. The texts of the seven antiphons implore God to come to earth and save his people. The first letter of each word following the ‘O’ form a reverse acrostic, spelling ERO CRAS (‘I will be tomorrow’), a response from God to his Church’s prayers. Four of the antiphons (and ‘O salutaris’) are scored for an ensemble of haute-contre (high tenor), tenor and bass voices and continuo. The sixth ‘O’ is scored for a solo haute-contre, two obbligato violins and continuo. Interestingly, Charpentier labels the vocal line ‘Mr Chopelet’, a singer known to be associated with the Paris Opéra. Given that Opéra singers regularly sang at the Jesuit church of Saint-Louis, where Charpentier was employed between 1688 and 1698, this annotation strengthens the possibility that the Jesuits commissioned this set of pieces. The two remaining antiphons (four and five) are scored for a four-part choir and orchestra. These both make use of expressive harmonies at the text ‘sedentem / sedentes in tenebris et umbra mortis’ (‘sitting / who sit in the darkness and in shadow of death’).

The motet Le reniement de St Pierre is a dramatic account of Peter’s denial of Christ, its text skilfully incorporating material from accounts of the Passion in all four Gospels. Sébastien de Brossard, composer, theorist and bibliophile, described it as ‘an oratorio in the Italian style’. Charpentier’s forces are relatively modest, involving only voices and continuo. Nevertheless, he takes every opportunity to intensify the text. Just before the cock crows, for instance, there is a quartet in which Peter vehemently denies knowing Jesus. Charpentier’s agitated music perfectly captures both Peter’s adamance and the persistent questions and accusations of the other three characters. Perhaps the most memorable passage in the work, though, is the final section. Over thirty bars long, this is built entirely on a setting of the words ‘flevit amare’ (‘wept bitterly’). Here the vocal lines weave a dense web of counterpoint, full of suspensions and other expressive dissonances. This powerful evocation of Peter’s remorse is reminiscent of the final chorus of lament in Carissimi’s Jephte; Charpentier clearly knew this work very well, since he himself made a copy of his teacher’s masterpiece.

Download Link Isra.Cloud

Ex Cathedra, Jeffrey Skidmore - Charpentier: Messe à quatre chœurs (2004)

My blog

Ex Cathedra, Jeffrey Skidmore - Charpentier: Messe à quatre chœurs (2004)

My blog

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads