Tracklist:

01. Polonaise in B Major, Op. 89

02. Seven Bagatelles, Op. 33: No. 1 in E-Flat Major, Andante grazioso quasi allegretto

03. Seven Bagatelles, Op. 33: No. 2 in C Major, Scherzo - Allegro

04. Seven Bagatelles, Op. 33: No. 3 in F Major, Allegretto

05. Seven Bagatelles, Op. 33: No. 4 in A Major, Andante

06. Seven Bagatelles, Op. 33: No. 5 in C Major, Allegro ma non troppo

07. Seven Bagatelles, Op. 33: No. 6 in D Major, Allegretto quasi andante

08. Seven Bagatelles, Op. 33: No. 7 in A-Flat Major, Presto

09. Two Rondos, Op. 51: No. 1 in C Major, Moderato e grazioso

10. Two Rondos, Op. 51: No. 2 in G Major, Andante cantabile e grazioso

11. Six Bagatelles, Op. 126: No. 1 in G Major, Andante con moto

12. Six Bagatelles, Op. 126: No. 2 in G Major, Allegro

13. Six Bagatelles, Op. 126: No. 3 in E-Flat Major, Andante

14. Six Bagatelles, Op. 126: No. 4 in B Major, Presto

15. Six Bagatelles, Op. 126: No. 5 in G Major, Quasi Allegretto

16. Six Bagatelles, Op. 126: No. 6 in E-Flat Major, Presto – Andante amabile e con moto – Tempo

17. Rondo a Capriccio in G Major, Op. 129

Ludwig van Beethoven had become a myth even during his lifetime. His deafness, his manners, his famously impossible character – along, of course, with the immense greatness of his works – all contributed to turn him into a living legend. Indeed, many features which were (rightly or wrongly) attributed to Beethoven became “necessary” qualities of the Romantic musician. A stereotype which only very rarely corresponded to reality – and certainly not in Beethoven’s case – began to emerge: true artists should disregard all conventions (either artistic or social), be seized by a kind of creative frenzy, and obey only the whims and caprices of their “inspiration”.

As said above, this did certainly not correspond to Beethoven’s figure or personality. True, he was frequently (but not always) rather intractable, but this largely depended on the limitations he had to endure due to his deafness and to the psychological impact it had on him. True, he did overturn many compositional standards and rules of the previous eras; yet, this pars destruens was always accompanied by, and prior to, a pars construens, which actually built the language of German Romantic music. True, he followed an inspiration and a musical imagination which remain almost unequalled in the history of music; yet, they germinated from the soil of hard work, and of an approach to composition which proceeded by trials and errors rather than by sudden strokes of lightning.

In spite of this, the Beethoven myth, nowadays abandoned by musicologists, still resists in collective imagination. And this Da Vinci Classics album substantially contributes to modify some of the inexactitudes of the traditional stereotype.

For example, even those who are unfamiliar with the Classical repertoire will have some superficial knowledge of Beethoven the symphonist: of course, Beethoven’s mastery of the large form was extraordinary, and he demonstrated his ability to sustain a musical discourse for very long stretches of time, enthralling and conquering his audiences. In this album, however, listeners are offered the opportunity to appreciate Beethoven’s skill as a miniaturist, and his artistry in concentrating the perfection of inspiration and form within the short space of a few minutes.

Moreover, the traditional stereotype portrays Beethoven as an always frowning and glowering figure. Here again, there is a grain of truth, but not the whole of it. Beethoven was fully capable of amusing himself, to enjoy a good joke, to laugh and make people laugh. The humorous Beethoven is splendidly represented in many of the works recorded here, and, once more, bringing a smile on the listeners’ faces is not easier than moving them to tears.

Under both of these viewpoints, Beethoven may be said to have points in common with Rossini – of all people. Actually, Beethoven knew some of Rossini’s works and had mixed feelings about them: he admired unconditionally Rossini’s Il Barbiere di Siviglia, even though he was slightly annoyed by the success and admiration surrounding the young Italian composer. Rossini, in turn, did not conceal his admiration for Beethoven, and allegedly visited him during his stay in Vienna in 1824. Their encounter is surrounded by a halo of legend, and therefore cannot be taken for granted. What is certain, however, is that the influence of Beethoven’s short masterpieces, such as those recorded here, was clearly in Rossini’s mind when he, many years later, would compose his own beautiful cycles of short piano pieces.

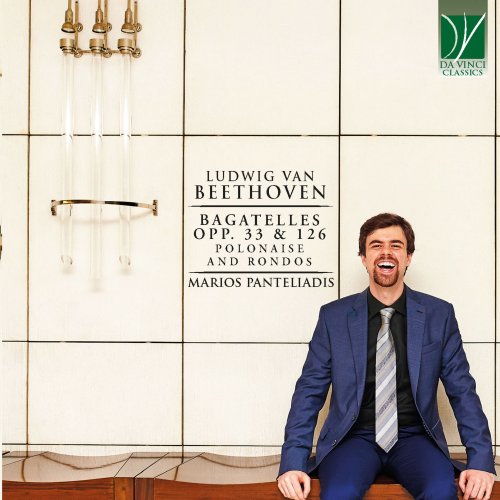

There is therefore a red thread uniting Marios Panteliadis’ first album, published in 2019 by Da Vinci Classics, and focusing on Rossini’s small-scale masterpieces (Quelques riens pour album) and the present CD, collecting lesser-known gems from Beethoven’s catalogue.

The works recorded here cover the full span of Beethoven’s creative life, from his earliest attempts as a composer to his final farewell to the piano. Indeed, on the original handwritten manuscript of Beethoven’s Bagatellen op. 33 the following annotation is found: “Par Louis van Beethoven, 1782”. In 1782, Beethoven was barely twelve years old, even though his exceptional talent had already manifested itself in unambiguous terms. As we will shortly see, this dating cannot refer to the whole cycle; however, between this early composition and the Bagatellen op. 126 all of Beethoven’s piano masterpieces are encompassed.

Beethoven composed three cycles of Bagatellen, although the term “cycle” is best applied only to the last of them, op. 126. In the case of his opuses 33 and 119, a single opus number embraces individual pieces whose composition dates could be very different, as demonstrated by their style. As said earlier, it is likely that only the first of the Bagatellen op. 33 (or perhaps just some ideas for it) dates back to Beethoven’s childhood. The seven pieces published under this title at the end of 1802 may have been created at various points of two decades; the occasion for their publication as a collected work is unknown. The title “bagatelle” was not new at Beethoven’s time; but even though it alludes to “trifles”, the pieces so labelled are real masterpieces. Among them, the first and third have a rather pastoral tone; the second, in the form of a Scherzo, is similar in style and kind to the first examples of this genre written by Beethoven. The fourth is more ethereal and enchanted, whilst the fifth is driven by a strong rhythmical impulse in its external parts, contrasting with a more intimate central section. The sixth bears the indication “con una certa espressione parlante”, by which Beethoven evidently requires an almost rhetoric expressivity, and the virtuoso seventh piece concludes the cycle on an explosion of brilliancy.

The same kind of extroverted brightness characterizes Rondo op. 129, composed around 1795 or slightly later in Vienna by an approximately 25-years old musician. This very celebrated piece is a masterful example of musical irony. Titled All’ingharese, quasi capriccio it evidently refers to the model of Haydn’s “Hungarian”-style compositions; however, Beethoven seems to have learnt from Haydn also his good-humoured wit, displayed in the subtitle, which is translated as “The Rage over a Lost Penny”. This Rondo was posthumously published by Diabelli in 1828, with completions silently added by the publisher-cum-editor. In spite of this scarce concern for philology and accuracy, its publication enthused many contemporaries, including Robert Schumann, who famously wrote: “it would be difficult to find anything merrier than this whim… It is the most amiable, harmless anger, similar to that felt when one cannot pull a shoe from off the foot”. In the same article, Schumann took the opportunity to recommend “naturalness” to young musicians, who ought to follow Beethoven’s example in the treatment of “real-life” situations. (Interestingly, if the reported meeting between Beethoven and Rossini did take place, Beethoven seems to have recommended to Rossini to remain faithful to his comical vein, without venturing in the tragic field. Evidently, “write of what you know” is a rather common piece of advice!).

The two other Rondos recorded here, published jointly as op. 51, date approximately to the same period (they possibly predate op. 129 by a few years); no. 1 was probably written around 1796-7, while no. 2 in 1800. Their published version was dedicated to Countess Henrietta von Lichnowsky, even though Beethoven had previously donated their manuscript to his young and fascinating pupil, Giulietta Guicciardi. Asking back for a present is not very good manners, but Beethoven amply excused himself by dedicating his “Moonlight” Sonata to Giulietta. In these two pieces, Beethoven experimented with formal aspects, attempting a combination between Rondo and Sonata form; the first piece is characterized by a charming naivety, occasionally interspersed with more intense and dramatic passages. The second is more capricious and voluble, but here too a contrasting section provides some respite, with a lyrical and tender style.

The next piece among those recorded here was composed in 1814, when Beethoven was 44. At that time, Vienna was hosting the Congress following the Napoleonic wars. The most important European rulers had convened, and the opportunities for mundanity were ubiquitous. In particular, one of Beethoven’s most faithful admirers and patrons, Count Razumovsky, who was the Russian Ambassador to the Hapsburg court, had contextually received the title of Prince by his Czar, and was duly celebrating the occasion. Beethoven was always invited to soirees and feasts, and was frequently “courted” (his words, as reported by his pupil Schindler) by the imperial family. On one such occasion, he wrote, on a theme provided by his friend Andrea Bertolini, a charming Polonaise, dedicated to the Czarina, who demonstrated her appreciation by donating a hundred ducats to the musician.

Ten more years elapsed before the composition of the Bagatellen op. 126, whose tone and style are in marked opposition with the nonchalant flair of the Rondos and of the Polonaise. Here, Beethoven’s language is distilled into drops of concentrated beauty. In this case, the six pieces were written in the order found in the publication, and should be played always as a cycle, also in consideration of their careful tonal plane. In this series we find poetry (as in the first), raptured agitation with oases of lyricism (as in the second), transfigured beauty (in the third), an impressive use of primeval musical gestures (in the fourth), simple elegance (in the fifth), and a sweet dance following a stormy initial Presto (in the sixth). These features, and many more, are combined so as to create a maximum of enchantment within a minimum length. Schumann, who had written so enthusiastically about Rondo op. 129, would also take a leaf or two out of Beethoven’s book: without Beethoven’s Bagatellen, we would probably have no Carnaval, no Kreisleriana, no Kinderszenen, since the whole genre of the piano miniature may be said to germinate from Beethoven’s masterful creations.