Tracklist:

01. Via Crucis, S.53: Einleitung. Vexilla Regis ("O Crux, Ave!")

02. Via Crucis, S.53: Station I. Jesis wird zum Tode verdammt

03. Via Crucis, S.53: Station II. Jesus trägt sein Kreuz

04. Via Crucis, S.53: Station III. Jesus fällt zum ersten Mal

05. Via Crucis, S.53: Station IV. Jesus begegnet seiner heiligen Mutter

06. Via Crucis, S.53: Station V. Simon von Kyrene hilft Jesus das Kreuz tragen

07. Via Crucis, S.53: Station VI. Sancta Veronica ("O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden")

08. Via Crucis, S.53: Station VII. Jesus fällt zum zweiten Mal

09. Via Crucis, S.53: Station VIII. Die Frauen von Jerusalem ("Nolite flere super me, sed super vos ipos et super filios vestros")

10. Via Crucis, S.53: Station IX. Jesus fällt zum dritten Mal

11. Via Crucis, S.53: Station X. Jesus wird entkleidet

12. Via Crucis, S.53: Station XI. Jesus wird ans Kreuz gsechlagen ("Crucifige")

13. Via Crucis, S.53: Station XII. Jesus stirbt am Kreuze ("Eli, Eli, lamma Sabacthani")

14. Via Crucis, S.53: Station XIII. Jesus wird kom Kreuz genommen

15. Via Crucis, S.53: Station XIV. Jesus wird ins Grab gelegt ("Ave Crux, spes unica")

16. Stabat Mater, S.172b

17. In festo transfigurationis Domini nostri Jesu Christi, S.188

18. Ave verum corpus, S.44

19. Album-Leaf 'B.A.C.H Fragment', S.166t

20. Deutsche Kirchenlieder, S. 669a: I. Es segne uns Gott

21. Deutsche Kirchenlieder, S. 669a: II. Gott sei uns gnädig (Der Kirchensegen)

22. Deutsche Kirchenlieder, S. 669a: III. Nun ruhen alle Wälder

23. Deutsche Kirchenlieder, S. 669a: IV. O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden

24. Deutsche Kirchenlieder, S. 669a: V. O Lamm Gottes

25. Deutsche Kirchenlieder, S. 669a: VI. Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan

26. Deutsche Kirchenlieder, S. 669a: VII. Wer nur den lieben Gott läßt walten

27. Le Crucifix, S.342/1

28. Le Crucifix, S.342/2

29. Le Crucifix, S.342/3

“Let us pass the time, each according to the measure of his vested talent, and let us ‘breathe eternity’ at the foot of the Cross of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ”. Thus wrote, on July 3rd, 1880, an aged Franz Liszt. For every Christian, the cross of Christ is both the ultimate challenge and the ultimate hope. It is a mystery of love, of grief, of life and death; a sight which both disturbs and fascinates, magnetizes and defies human understanding.

Franz Liszt was deeply attracted by the Christian faith since his youthful years. Following his studies of piano and composition in Vienna and Paris, and subsequent to his father’s death (1827), Liszt started teaching music in Paris. Twice during those years, he expressed the wish to enter a seminary and become a priest, but was discouraged by his mother and by a priest. He then embarked in an extremely successful career as a piano virtuoso, perhaps the greatest of all times; later, he met Princess Carolyne Sayn-Wittgenstein, a married woman intensely interested in religious matters. They made a number of attempts to have Carolyne’s preceding marriage annulled by the Roman Catholic authorities, but these attempts failed. Nonetheless, Liszt’s own religious interests renewed as a result of his relationship to the princess. In 1858 he was given an honorary membership in a Franciscan congregation in Budapest, and in 1861 they both settled in Rome.

While living in the center of Roman Catholicism, Liszt became acquainted with leading figures of the religious and musical milieux of the day. Even Pope Pius IX visited him at his home. During that period, both his musical work and his personal life were strongly intertwined with Catholicism, and in 1865 he received the four minor orders of porter, lector, exorcist, and acolyte. The quasi-monastic life he led during those years in Rome was then followed by further years of intense odyssey, especially around the three poles of his musical activity as a composer, conductor, and teacher – i.e., in Rome, Budapest, and Weimar. From then on and until his death in 1886 he composed numerous works on religious subjects.

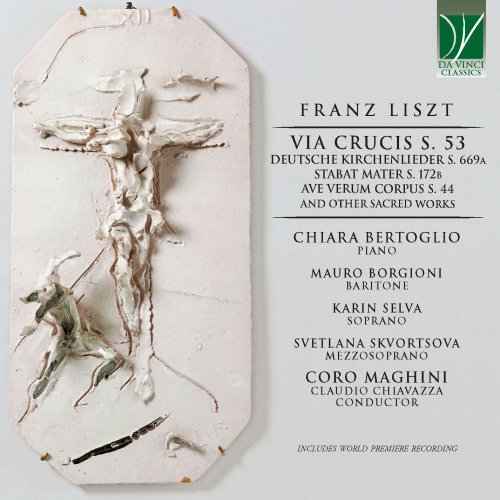

This Da Vinci Classics album focuses mainly (albeit not exclusively) on Liszt’s final decade, and develops a number of red threads, all intertwined with each other: the Cross, Jesus, his Mother, the city of Rome and J. S. Bach; on the musical plane, the dialogue between piano and voices in a chamber music fashion. All of these are found, both summarized and exalted, in the Via Crucis. This work exists in several original versions. The one recorded here can be performed by the solo voices and choir accompanied by piano, organ or harmonium, but there are versions for solo organ, solo piano and four-hand piano duet. The work sets to music the typically Catholic devotion of the “Stations of the Cross”, a spiritual (but also physical) itinerary whereby the faithful follow the stages of Christ’s Passion, meditating and contemplating on the mystery of his redemptive suffering.

Already in 1874 Liszt had expressed his desire to write such a work, and he probably began it in 1875. On November 20th, 1875, he wrote to Olga von Meyendorff: “Later on, I’ll go ahead with the composition of Via crucis… which I started at the Colosseum, [which I could see] when I lived very close by, at Santa Francesca Romana”. On October 17, 1877 he wrote to Carolyne: “You have admirably prepared the texts for the Via crucis. I will try to thank you appropriately through my composition, which I would like to begin immediately, but alas! I must wait until next summer”. This reveals Carolyne’s engagement in the project, which was finished by the end of October, as he wrote to Olga: “These last two weeks I have been completely absorbed in my Via crucis. It is at last complete (except for the indications of the fortes, pianos, etc.) – and I still feel quite shaken by it”.

The Stations proper are preceded by a Hymn, the Medieval Vexilla regis prodeunt, attributed to Venantius Fortunatus: here, the Cross is saluted as the “only hope” of humankind, and as a royal banner for Christ’s ultimate victory. Not all of the fourteen Stations include the choir’s active participations. Some are set for solo piano, and represent a musical contemplation of the situation’s affective content; in others, short phrases, mainly taken from the Gospels, are sung by vocal soloists, and framed or preceded by piano passages. In the first Station, a solo Bass interprets the figure of Pilate, while a solo Baritone later interprets Christ, uttering some of Jesus’ last words (as happens, for example, in the extremely complex Station XII) or fragments from prayers which resonate with Christ’s personality and feelings (“Ave Crux”). The motif to which these words of Venantius’ hymn are set thus becomes one of the many motifs employed by Liszt in order to weave a net of references among the Stations, whose musical language is extremely sober and yet very forward-looking. The introductory Hymn opens with the “crux motif”, excerpted from yet another Gregorian hymn (Crux fidelis), and presented also in its inversion; it will resound also at the very end of the Via Crucis. In Stations II and V (whereby Jesus is first loaded with the cross, and later helped by Simon of Cyrene), another motif is found: it is the inversion of the BACH motif. This same motif, in its original form, resounds also in Station VI, where it precedes a touching rendition of O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden, a Lutheran Chorale best known today for its various settings in Bach’s St Matthew Passion.

In the same Station (the sixth) another short motif of six notes is heard, which resounds also in Stations VIII and XIII, and that can therefore be understood as a motif of feminine compassion: Veronica, the daughters of Jerusalem, and Christ’s mother, who receives her dead son in a musical Pietà.

Still more evident is the recurring use of the plainchant tune of the Stabat Mater, on a poem by Jacopone da Todi evoking Mary’s sorrow. It is heard, sung by three female soloists, in the three Stations contemplating Christ’s falls (III, VII and IX), and it is played by the piano in Station XIII, the Deposition. Liszt also uses liberally chromatic scales (for example in Stations IV, VIII, X and XIII), evidently as a symbol of interior sorrow. Another Lutheran Chorale is found in Station XII, where Jesus’ death is painfully contemplated on the notes of O Traurigkeit.

These two Lutheran chorales are also found in a collection compiled by Liszt in the same year of the Via Crucis (1878), i.e. the Zwölf alte deutsche geistliche Weisen for solo piano, which he composed, “in sincere piety”, as he wrote on February 16th, 1879 (when he also mentioned that the Via Crucis was in the copy stage for publication). In this collection are also found, in a solo piano version, the seven Deutsche Kirchenlieder und liturgische Gesänge (S. 669a) recorded here. For these Kirchenlieder, Liszt left various indications as concerns the accompaniment (organ, harmonium, piano, or a free choice among these instruments); however, in consideration of Liszt’s original version for solo piano, coeval with the Via Crucis, and of the songs’ chamber music style, we propose here a version accompanied by the piano.

In those same years he also composed another set of Lieder for voice and piano, setting a quatrain by Victor Hugo. The poem, originally titled Écrit au bas d’un crucifix (1842, thus written at the time when Liszt met Hugo in Paris), is included in a collection published in 1856 (Les contemplations). Liszt wrote the two first settings in 1879, the third in 1881, and revised the work in 1884. Liszt was deeply interested in Hugo’s poetry and novels, and set many of his lyrics to music. Le crucifix is almost shockingly modern, with daring harmonies and with an astonishing loneliness of the voice, which is only rarely supported by the piano. (The same applies to Christ’s utterances in the Via Crucis). Liszt thus managed to convey the feeling of abandonment and forsakenness experienced by Christ on the cross.

Sharing the same fate of the solo piano version of the Chorales, another original “sacred” work for solo piano by Liszt remained unpublished during his lifetime: it is In festo transfigurationis Domini nostri Jesu Christi, dated August 6th, 1880 (i.e. on the Solemnity of the Transfiguration of Christ). It is a quiet, sweet yet majestic contemplation of the perfect beauty of Christ, who showed Himself in his perfection to his disciples, before enduring the Passion.

The other major solo piano work recorded here is a Stabat Mater, probably written as early as 1847, but which is based, as a theme with variations, on the medieval Sequence sung thrice and heard four times in the Via Crucis. The episodes of introduction and transition are also found in Liszt’s arrangement of Rossini’s Stabat Mater (“Cujus animam”).

It is to another great musician that Liszt’s Ave verum refers: Liszt in fact had studied and transcribed Mozart’s Ave verum demonstrating his deep admiration for the earlier masterpiece. In comparison with Mozart’s, Liszt’s a cappella version is richer in chromatic movements, underpinning the most painful sections of the text (“passus”, “immolatus”, “in cruce”). This extraordinary setting seems to translate the words, one by one, into an intense contemplation.

Finally, this album includes an absolute rarity: an extremely short Fragment for solo piano, in which the left hand plays obsessively the notes of the BACH motif. It seems to be a draft for what will become the Prelude and Fugue on the name of Bach S260i (1855); it could evidently be used as a Prelude to many pieces, by virtue of its “open” ending on a diminished seventh chord.

Together, these works portray Liszt’s fascination for the Cross and his unceasing contemplation of its mystery; they constitute a repository of touching, and yet ascetic beauty, capable of moving the soul deeply and lift the listener’s gaze to the crucified Christ.