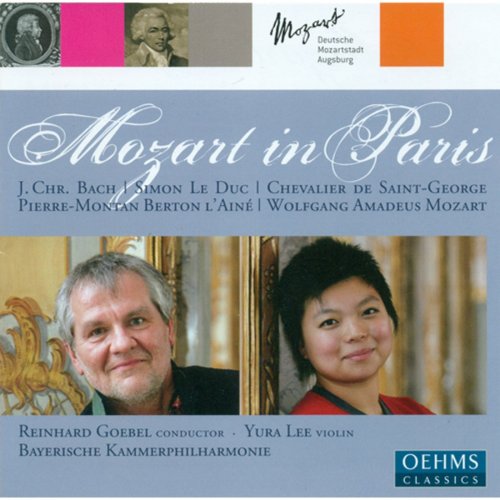

Yura Lee, Bayerische Kammerphilharmonie, Reinhard Goebel - Mozart in Paris (2007)

BAND/ARTIST: Yura Lee, Bayerische Kammerphilharmonie, Reinhard Goebel

- Title: Mozart in Paris

- Year Of Release: 2007

- Label: Oehms Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless

- Total Time: 01:06:29

- Total Size: 271 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

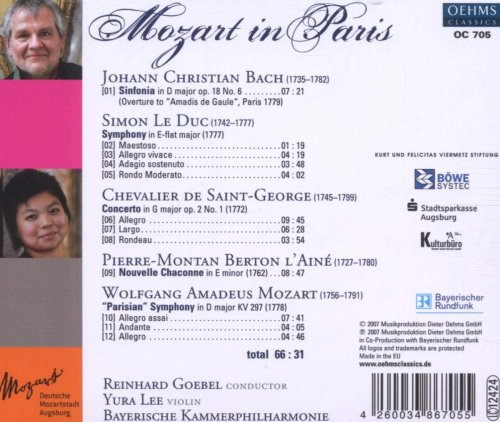

Tracklist

01. Amadis de Gaule, W. G39: Overture

02. Symphony No. 3 in E flat major: I. Maestoso

03. Symphony No. 3 in E flat major: I. Allegro vivace

04. Symphony No. 3 in E flat major: II. Adagio sostenuto

05. Symphony No. 3 in E flat major: III. Rondo moderato

06. Violin Concerto in G major, Op. 2, No. 1: I. Allegro

07. Violin Concerto in G major, Op. 2, No. 1: II. Largo

08. Violin Concerto in G major, Op. 2, No. 1: III. Rondeau

09. Chaconne in E minor

10. Symphony No. 31 in D major, K. 297, "Paris": I. Allegro assai

11. Symphony No. 31 in D major, K. 297, "Paris": II. Andante

12. Symphony No. 31 in D major, K. 297, "Paris": III. Allegro

Get going to Paris! …and soon; get important people on your side – either a Caesar or nothing; the single-minded idea to see Paris should have guarded you against all other diverging notions. It is from Paris that the fame and name of a man with huge talent reaches the whole world; there, nobles treat people of genius with the greatest regard, courteousness and patronage…” (Leopold Mozart to his son, 2/12/1778). Several months before, Wolfgang Amadeus had set off from the hated city of Salzburg, accompanied by his mother, to look, as it were, for a position. Leopold – whom Princely Archbishop Colloredo would grant no leave – was both annoyed and alarmed, because his now adult “wunderkind” was setting off on a journey without him. In the end, Leopold’s dark premonitions were confirmed: “Wolferl’s” passion for Aloysia Weber was enkindled in Mannheim, causing him to postpone continuing to Paris time and again until his father lost patience and put his foot down with the words quoted above, and then, after finally arriving in Paris, Anna Maria Mozart fell exceedingly ill and died on July 3, 1778. In addition, the city on the Seine did not provide as “corteous” a reception as Leopold had hoped…

What was Paris’s musical life like – from which the Mozarts had expected so much? France was an absolutist country in which the kings had had all power since Louis XIV. In the 17th century, this king had seen music as the means to express his unlimited powers, leading to the foundation of the “Académie royale de musique” in 1669, which provided official support for music, but on the other hand, placed it under governmental control. Thus, before the rise of the “Concert spiritual”, it was difficult to organize public concerts in Paris, because only the royal music academy had the privilege of doing this. After Louis XIV’s death in 1715, the court had gradually lost its dominant position. It was just this withdrawal to Versailles that caused the court’s influence on the capital, where many longed for more independent musical organization, to wane.

The “Concert spiritual” series can be seen as a direct reaction to this. It existed from 1725 until 1791 in Paris and was pioneering for musical taste in 18th century France. It was founded by royal chapel composer and oboist Anne-Danican Philidor (1681–1728), who had wrested permission for this from Louis XV and the Académie. Concerts were only permitted on days when the opera did not perform (Lent, Sundays and holidays). At first – in keeping with the title of the series – only sacred music was performed in these concerts. In the course of time, however, secular works also became part of the programs. Concerts in the series were performed in the “Salle des Cent Suisses” in the Tuileries palace, the city castle of the French rulers which was originally the architectonic closure of the horseshoe-shaped Louvre formation in the Parc de Tuileries. This hall burned to the ground in 1871 and has completely disappeared today.

We do have all programs of the concerts, however, and know exactly what was performed because all titles have been passed down. Uncertainty arises solely in the case of the symphonies, because only “a new symphony” of this or that composer is noted. When a certain symphony was performed several times – which was the rule –, the programs almost always contain the words: “a symphony” and the name of its author. It is certainly accurate to imagine the musical scene in Paris as being just as large as the scene in Vienna at the same time. In the latter city, it can be assumed that some 400 professional freelance musicians were active in 1780.

The “Concert spiritual” had a competitor in the “Concert des Amateurs”, which had been originally founded in 1769 in the Marais quarter, in the Hôtel de Soubise, today’s site of the Archives nationals, and placed under the leadership of François-Joseph Gossec (1734–1829). In 1773, Joseph Boulogne de Saint-George (1745–1799) – a noble, violin virtuoso, composer, conductor and fencing master of African ancestry who was one of the age’s most scintillating figures – was named its new director. The “Concert des Amateurs” presented contemporary instrumental music and smaller music-theatrical works until 1781. After being disbanded, it was replaced by the “Concert de la Loge Olympique”, also led by Saint-George. By 1784, it had ordered the six symphonies from Joseph Haydn which have gone down in music history as the “Paris Symphonies”.

The program on this CD was never played per se at a “Concert spirituel”. The violin concerto by Chevalier de Saint-George, possibly the most significant violinist during the development of the classical violin technique, was no longer performed at the time of Mozart’s Paris stay in 1778/1779. In addition, an absolutely authentic presentation of the works of one “Concert spirituel” would last at least three hours. The concerts were extremely long and contained an exotic mixture of works: the repertoire ranged from French and Italian arias to sonatas and then on to symphonies and solo concertos. In contrast, this recording represents the compositional achievements that the 22-year-old Mozart found in Paris.

It was here that the Salzburg native met with Johann Christian Bach (1735–1782) for the last time. Bach had been commissioned to write the opera Amadis de Gaules and thus came from England to Paris. Despite all the joy of the reunion, Mozart was sobered to some extent by the fact that Bach did not approach him as uninhibitedly as he had the one-time “wunderkind”, whom Bach had nothing less than indulged 14 years previously. In the meantime, J.C. Bach must have seen a competitor in his younger colleague. Bach’s Symphony in D Major was simultaneously the overture to Amadis de Gaules, and premiered some six months after the “Concert spirituel”-premiere of Mozart’s “Paris Symphony” K. 297.

Strictly speaking, Mozart’s own personality was his biggest obstacle in Paris. He was haughty, arrogant and intolerant, and would have had to be much more patient and wait much longer than his character would allow. The French most certainly perceived Mozart’s skepticism towards them… And the royal court in Versailles? “In May 1778, it had completely other troubles than ‘taking a Mozart under its wings’. Queen Marie Antoinette was pregnant for the first time – after eight long years of vain endeavors, during which not only Empress Maria Theresia constantly intervened in writing, but also Joseph II himself traveled personally to Paris to tell his brother-in-law Louis XVI ‘how it is done’”, as Reinhard Goebel, conductor of this imaginary “Concert spiritual” mischievously notes. The works of Simon Le Duc (1742–1777) and Pierre-Montan Berton l’Ainé (1727–1780), recorded here on CD for the first time, are of particular significance for Goebel, who says, “One should approach these compositions with complete impartiality and then ask what Mozart could have learned from them or how others could have been ahead of him. It is always part of my artistic work to emphasize the concurrency of certain things – and not just to hop from one masterpiece to another. After all, music has uncommonly strong historicity, which does not mean in the slightest that it is antiquated, but that it relates to something that really exists. It comes from somewhere; i.e. it has roots… It is in this network that I want to integrate it, in order to be able to show connections.”

01. Amadis de Gaule, W. G39: Overture

02. Symphony No. 3 in E flat major: I. Maestoso

03. Symphony No. 3 in E flat major: I. Allegro vivace

04. Symphony No. 3 in E flat major: II. Adagio sostenuto

05. Symphony No. 3 in E flat major: III. Rondo moderato

06. Violin Concerto in G major, Op. 2, No. 1: I. Allegro

07. Violin Concerto in G major, Op. 2, No. 1: II. Largo

08. Violin Concerto in G major, Op. 2, No. 1: III. Rondeau

09. Chaconne in E minor

10. Symphony No. 31 in D major, K. 297, "Paris": I. Allegro assai

11. Symphony No. 31 in D major, K. 297, "Paris": II. Andante

12. Symphony No. 31 in D major, K. 297, "Paris": III. Allegro

Get going to Paris! …and soon; get important people on your side – either a Caesar or nothing; the single-minded idea to see Paris should have guarded you against all other diverging notions. It is from Paris that the fame and name of a man with huge talent reaches the whole world; there, nobles treat people of genius with the greatest regard, courteousness and patronage…” (Leopold Mozart to his son, 2/12/1778). Several months before, Wolfgang Amadeus had set off from the hated city of Salzburg, accompanied by his mother, to look, as it were, for a position. Leopold – whom Princely Archbishop Colloredo would grant no leave – was both annoyed and alarmed, because his now adult “wunderkind” was setting off on a journey without him. In the end, Leopold’s dark premonitions were confirmed: “Wolferl’s” passion for Aloysia Weber was enkindled in Mannheim, causing him to postpone continuing to Paris time and again until his father lost patience and put his foot down with the words quoted above, and then, after finally arriving in Paris, Anna Maria Mozart fell exceedingly ill and died on July 3, 1778. In addition, the city on the Seine did not provide as “corteous” a reception as Leopold had hoped…

What was Paris’s musical life like – from which the Mozarts had expected so much? France was an absolutist country in which the kings had had all power since Louis XIV. In the 17th century, this king had seen music as the means to express his unlimited powers, leading to the foundation of the “Académie royale de musique” in 1669, which provided official support for music, but on the other hand, placed it under governmental control. Thus, before the rise of the “Concert spiritual”, it was difficult to organize public concerts in Paris, because only the royal music academy had the privilege of doing this. After Louis XIV’s death in 1715, the court had gradually lost its dominant position. It was just this withdrawal to Versailles that caused the court’s influence on the capital, where many longed for more independent musical organization, to wane.

The “Concert spiritual” series can be seen as a direct reaction to this. It existed from 1725 until 1791 in Paris and was pioneering for musical taste in 18th century France. It was founded by royal chapel composer and oboist Anne-Danican Philidor (1681–1728), who had wrested permission for this from Louis XV and the Académie. Concerts were only permitted on days when the opera did not perform (Lent, Sundays and holidays). At first – in keeping with the title of the series – only sacred music was performed in these concerts. In the course of time, however, secular works also became part of the programs. Concerts in the series were performed in the “Salle des Cent Suisses” in the Tuileries palace, the city castle of the French rulers which was originally the architectonic closure of the horseshoe-shaped Louvre formation in the Parc de Tuileries. This hall burned to the ground in 1871 and has completely disappeared today.

We do have all programs of the concerts, however, and know exactly what was performed because all titles have been passed down. Uncertainty arises solely in the case of the symphonies, because only “a new symphony” of this or that composer is noted. When a certain symphony was performed several times – which was the rule –, the programs almost always contain the words: “a symphony” and the name of its author. It is certainly accurate to imagine the musical scene in Paris as being just as large as the scene in Vienna at the same time. In the latter city, it can be assumed that some 400 professional freelance musicians were active in 1780.

The “Concert spiritual” had a competitor in the “Concert des Amateurs”, which had been originally founded in 1769 in the Marais quarter, in the Hôtel de Soubise, today’s site of the Archives nationals, and placed under the leadership of François-Joseph Gossec (1734–1829). In 1773, Joseph Boulogne de Saint-George (1745–1799) – a noble, violin virtuoso, composer, conductor and fencing master of African ancestry who was one of the age’s most scintillating figures – was named its new director. The “Concert des Amateurs” presented contemporary instrumental music and smaller music-theatrical works until 1781. After being disbanded, it was replaced by the “Concert de la Loge Olympique”, also led by Saint-George. By 1784, it had ordered the six symphonies from Joseph Haydn which have gone down in music history as the “Paris Symphonies”.

The program on this CD was never played per se at a “Concert spirituel”. The violin concerto by Chevalier de Saint-George, possibly the most significant violinist during the development of the classical violin technique, was no longer performed at the time of Mozart’s Paris stay in 1778/1779. In addition, an absolutely authentic presentation of the works of one “Concert spirituel” would last at least three hours. The concerts were extremely long and contained an exotic mixture of works: the repertoire ranged from French and Italian arias to sonatas and then on to symphonies and solo concertos. In contrast, this recording represents the compositional achievements that the 22-year-old Mozart found in Paris.

It was here that the Salzburg native met with Johann Christian Bach (1735–1782) for the last time. Bach had been commissioned to write the opera Amadis de Gaules and thus came from England to Paris. Despite all the joy of the reunion, Mozart was sobered to some extent by the fact that Bach did not approach him as uninhibitedly as he had the one-time “wunderkind”, whom Bach had nothing less than indulged 14 years previously. In the meantime, J.C. Bach must have seen a competitor in his younger colleague. Bach’s Symphony in D Major was simultaneously the overture to Amadis de Gaules, and premiered some six months after the “Concert spirituel”-premiere of Mozart’s “Paris Symphony” K. 297.

Strictly speaking, Mozart’s own personality was his biggest obstacle in Paris. He was haughty, arrogant and intolerant, and would have had to be much more patient and wait much longer than his character would allow. The French most certainly perceived Mozart’s skepticism towards them… And the royal court in Versailles? “In May 1778, it had completely other troubles than ‘taking a Mozart under its wings’. Queen Marie Antoinette was pregnant for the first time – after eight long years of vain endeavors, during which not only Empress Maria Theresia constantly intervened in writing, but also Joseph II himself traveled personally to Paris to tell his brother-in-law Louis XVI ‘how it is done’”, as Reinhard Goebel, conductor of this imaginary “Concert spiritual” mischievously notes. The works of Simon Le Duc (1742–1777) and Pierre-Montan Berton l’Ainé (1727–1780), recorded here on CD for the first time, are of particular significance for Goebel, who says, “One should approach these compositions with complete impartiality and then ask what Mozart could have learned from them or how others could have been ahead of him. It is always part of my artistic work to emphasize the concurrency of certain things – and not just to hop from one masterpiece to another. After all, music has uncommonly strong historicity, which does not mean in the slightest that it is antiquated, but that it relates to something that really exists. It comes from somewhere; i.e. it has roots… It is in this network that I want to integrate it, in order to be able to show connections.”

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads