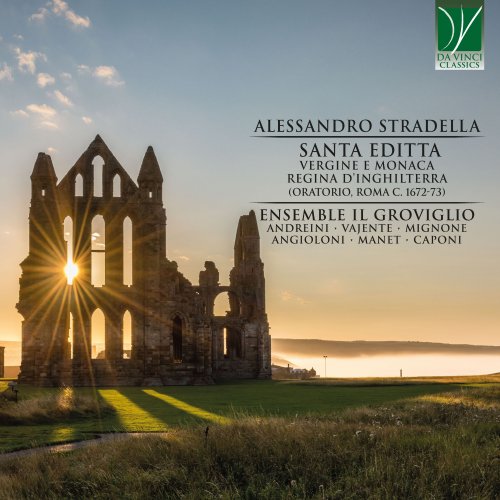

Silvia Vajente, Laura Andreini, Sylvain Manet, Francesca Caponi, Marco Angioloni, Michele Mignone, Ensemble Il Groviglio - Alessandro Stradella: Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra (2021)

BAND/ARTIST: Silvia Vajente, Laura Andreini, Sylvain Manet, Francesca Caponi, Marco Angioloni, Michele Mignone, Ensemble Il Groviglio

- Title: Alessandro Stradella: Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra

- Year Of Release: 2021

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless

- Total Time: 00:58:11

- Total Size: 327 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Aria: "Il premio felice"" (Humiltà)

02. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "De' miei veri consigli"" (Humiltà)

03. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Aria: "Speranze gradite"" (Santa Editta)

04. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Codarda, e che, vaneggio?"" (Santa Editta)

05. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Duetto: "A che giova il regnar"" (Grandezza, Nobiltà)

06. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "O del ciel saggi detti"" (Santa Editta)

07. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Aria: "Se l'arciero lusinghiero"" (Santa Editta)

08. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "D'un tuo servo fedel" - Aria: "Dunque il ciel tanti contenti"" (Santa Editta)

09. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Quei diporti che in dono"" (Santa Editta)

10. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Aria: "Così fuggite"" (Santa Editta)

11. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Di chi brama il tuo ben" - Aria: "Chi pianti e sospiri"" (Bellezza)

12. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Pregio che poco dura" - Aria: "Che piacer non di si dee"" (Santa Editta)

13. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Aria: "Bellezze rapine"" (Santa Editta)

14. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Senza offendere il giusto"" (Grandezza)

15. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Terzetto: "O come si mira sovente"" (Nobiltà, Grandezza, Senso)

16. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Se vago in oriente"" (Santa Editta)

17. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Aria: "Piagge amene"" (Santa Editta)

18. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Tua ragion non comprendo"" (Grandezza, Humiltà)

19. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Duetto: "Chi può le nostr'alme"" (Grandezza, Humiltà)

20. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Fra le porpore e gli ostri" - Aria: "Su, su, cingetemi"" (Santa Editta)

21. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Con non più intesi accenti"" (Bellezza, Santa Editta, Senso)

22. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Aria: "A punir le colpe un'alma"" (Senso)

23. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Alle vigilie intenti"" (Grandezza, Santa Editta, Nobiltà, Bellezza)

24. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Terzetto: "Mal nato é il desire"" (Nobiltà, Grandezza, Bellezza)

25. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Della vita mortal nel breve giorno"" (Santa Editta)

26. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Dite su, pompe che siete?"" (Santa Editta)

27. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Duetto: "Siamo scorta a voi mortali"" (Nobiltà, Grandezza)

28. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Aria: "Spesso un regio ambito soglio"" (Grandezza)

29. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Dite su, piacer, che siete?"" (Santa Editta)

30. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Duetto: "Noi sirene siamo all'alme"" (Grandezza, Senso)

31. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Aria: "Chi i suoi lumi al vostro canto" - Recitativo: "Dite su, piacer, che siete?"" (Senso, Santa Editta)

32. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Terzetto: "Noi sirene siamo all'alme"" (Nobiltà, Grandezza, Senso)

33. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Dunque la reggia abbandonar t'aggrada?"" (Senso, Santa Editta, Nobiltà)

34. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra: "Duetto "Bella luce del ciel"" (Santa Editta)

35. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Agi, pompe, beltà, dilette e regni"" (Santa Editta)

36. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Aria: "Così disciolta da cure frali"" (Santa Editta)

37. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Arresta un sol momento"" (Bellezza, Santa Editta)

38. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Aria: "L'orme stampi veloci il piè"" (Santa Editta)

39. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Qui tace la reina"" (Grandezza)

40. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Terzetto: "A notte breve"" (Nobiltà, Grandezza, Bellezza)

41. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Di profeta real s'odan gli accenti"" (Humiltà)

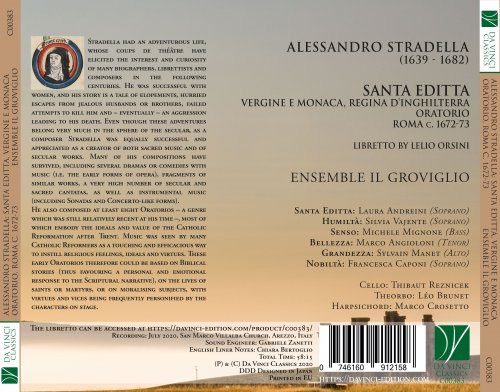

Those familiar with art history are likely to know the figure of Michelangelo Merisi, aka Caravaggio, not only for his magnificent paintings, iconic of the early Baroque style, but also for the mysterious circumstances of his violent death. His paintings, both in the sacred and in the secular sphere, still fascinate and charm thanks to their depth, to their chiaroscuro, and to the inextricable intertwining of ecstasy, holiness and sensuous overtones. Much of the above could apply both to the biography and to the output of Alessandro Stradella, another major artist of the Italian Baroque, though one whose masterpieces are found in the domain of the sounds instead of the colours.

Stradella had an adventurous life, whose coups de théâtre have elicited the interest and curiosity of many biographers, librettists and composers in the following centuries. He was successful with women, and his story is a tale of elopements, hurried escapes from jealous husbands or brothers, failed attempts to kill him and – eventually – an aggression leading to his death.

Even though these adventures belong very much in the sphere of the secular, as a composer Stradella was equally successful and appreciated as a creator of both sacred music and of secular works. Many of his compositions have survived, including several dramas or comedies with music (i.e. the early forms of opera), fragments of similar works, a very high number of secular and sacred cantatas, as well as instrumental music (including Sonatas and Concerto-like forms).

He also composed at least eight Oratorios – a genre which was still relatively recent at his time –, most of which embody the ideals and value of the Catholic Reformation after Trent. Music was seen by many Catholic Reformers as a touching and efficacious way to instill religious feelings, ideals and virtues. These early Oratorios therefore could be based on Biblical stories (thus favouring a personal and emotional response to the Scriptural narrative), on the lives of saints or martyrs, or on moralising subjects, with virtues and vices being frequently personified by the characters on stage.

The most common subjects were, predictably, the protagonists of Biblical episodes which possessed a particularly strong dramatic power (such as Judith and Holofernes, or Jephthah’s daughter, to name but two of the most frequently chosen), or, among the saints, the most famous ones and (even more importantly) those whose feast-day required a special and solemn celebration.

To be sure, St. Edith would not have qualified in any of the preceding categories. She was an English princess whose short life blossomed just before the year 1000. St. Edith’s mother, Wilfrida, a noblewoman, had been a nun at Wilton Abbey, but was abducted by Edgar, king of England (who was known, ironically, by the title of “Peaceful”). Edgar did penance for his crime by not wearing his crown for seven years; Edith was born, and, of course, was destined to become the wife of a man of royal descent. However, Wilfrida did not remain at Edgar’s side for long: approximately one year after Edith’s birth, she went back to the monastery with her child, was elected abbess and entrusted her daughter to the nuns who took care of her education (along with that of other noble girls). As reported by Edith’s biographer, the monk Goscelin, the girl used to dress sumptuously, in spite of her intense religiosity; she maintained that “pride could exist under the garb of wretchedness, but a mind could be pure under rich vestments”. Actually, under her mother Wilfrida’s rule, the nuns wore white robes embroidered in gold, “to the glory of God”. When her time came to choose her vocation, Edith preferred to remain in the monastery, renouncing the splendour of a queen’s life; she died very young, and was renowned for her wisdom, knowledge, beauty and holiness.

Her feast-day was celebrated on September 16th, and a seventeenth-century Italian hagiography narrates her story as follows: “St. Edith, the daughter of Edgar King of England, preferred the humility of Christ’s Cross to her father’s kingdom’s pomp and to the vanity of worldly greatness. […] Having become a nun, she greatly loved the holy humility, exercising works of Christian piety and serving the other nuns in their humblest needs. She refused, due to humility, the title of Abbess, choosing to be the least of all rather than to rule the others” (Delle vite de’ santi d’ogni mese, Bologna, 1675).

It clearly appears from these lines that humility was the trait for which Edith was most praised; it is not therefore by chance that a character by the name of Humility is found in Stradella’s Oratorio, contending with other qualities (such as Greatness, Nobility, Sensuality and Beauty) for the young princess’ heart. In fact, even though the story of St. Edith is not devoid of dramatic interest and could provide an intriguing libretto, the Oratorio by Stradella hardly narrates any episode of the saint’s biography. Rather, it stages the interior struggle of the protagonist, who is drawn to monastic life but who has to listen to the advice of these personified qualities. They in fact attempt to convince her to take the crown instead of the veil.

St. Edith is therefore the only real, human character on stage. This confers to her person a particularly powerful aura, and draws the audience’s attention on her feelings and personality. While the other singers represent “just” disembodied qualities, she is the only human being whose heart may encompass different, and sometimes conflicting, feelings.

Thus, once more the question arises: why does an English saint who lived more than six hundred years earlier and who was not the object of particular devotion in Italy become the protagonist of an Oratorio?

The most likely answer is also rather puzzling. It has been argued that the (unknown) occasion for the creation and premiere of Santa Editta may have been the wedding, in 1673, of Maria Beatrice d’Este, a fifteen-years old noblewoman, with James Stuart, who was forty-one and was the heir to the English throne. There was nothing strange in the idea of celebrating an aristocratic wedding with an oratorio; moreover, James’ nationality could encourage the librettist to find a subject related with English sacred history. As happened to virtually all aristocratic weddings of the time, the marriage had been combined for political reasons: King Louis XIV of France, in the midst of the confessional turmoil following the Reformations, wanted a Catholic couple on the English throne, and was supported by the Pope.

Similar to St. Edith, however, the intended bride was personally inclined to become a nun; similar to St. Edith’s mother, moreover, the bride’s mother, Laura Martinozzi, favoured her daughter’s wishes. When, however, the Pope himself wrote a letter to Maria Beatrice requesting her consent to the marriage with James, the two women could not refuse anymore.

On the one hand, then, it is understandable that an Oratorio about a holy English princess could celebrate the wedding of an Italian girl to an English prince. On the other, however, it strikes us as entirely inappropriate that the story of a nun who was allowed to choose the veil instead of the crown should celebrate the wedding of another girl who would have preferred to have the same power to choose.

Moreover, as we have seen, St. Edith was famous for her humility, but her appreciation of the royal garments did not entirely conform to the stereotype of a humble nun. This ambivalence is also found in the Oratorio: perhaps not in the libretto, created by the nobleman Lelio Orsini (c. 1623-1696), a prince from Latium, but certainly in the music written by Stradella.

In fact, the protagonist sings numerous arias, encompassing a wide range of moods, styles and affections. In comparison with other coeval saints, the chronicle by Goscelin tells us much about the character of this young saint, who comes to life not as a bidimensional portrait but rather as a real woman (we even learn that she had several pet animals, and that one of her miracles involved rescuing her chest of dresses from a fire!). And even though the libretto’s words are much less lively, the music supplies the drama and vivacity surrounding the protagonist’s figure.

St. Edith’s refreshing and youthful personality is in fact portrayed in some of her arias, sparkling with fantasy and exuberance. This is the case, for example, with Speranze gradite, in a joyful triple time evoking dance steps and with virtuoso passages of great musical appeal. Even more dazzling is Se l’arciero lusinghiero, where the piercing and flying arrows are very graphically depicted through dazzling scales. The protagonist’s primacy, however, is masterfully balanced by the interventions of the other singers.

Similar to the other known oratorios by Stradella, in fact, Santa Editta is sung in Italian and is divided into two parts. Even though there are six characters, the Oratorio requires only five singers (once more, as in the other similar works by the composer), since one singer may interpret two roles.

There is a clear correspondence between the vocal ranges and the “personality” of the characters embodying the qualities who speak with Edith. The most sensuous and earthly character, Sensuality, is sung by a bass, whose low voice seems to associate him to the basest passions. He is the first character to appear in the Oratorio after the two positive personae (St. Edith and Humility); his arguments are also those which Edith can counter more easily. He is also the first to disappear from the Oratorio, whereas Beauty, Greatness and Nobility remain until the very end.

Beauty is in turn a “material” quality, but it is endowed with a higher status, since Beauty is also a quality of the Godhead. It is therefore symbolized by a tenor voice, possibly suggesting the beauty of a young male lover (as happens in most operas). Greatness is interpreted by a contralto, a voice whose range is halfway through the entire compass of the human voice. In fact, a love for greatness may encourage both holiness and depravity: it can lead to a life of virtue or to a lust for power. The two remaining characters are sung by a soprano, thus showing that Nobility and Humility can coexist. In fact, these are the two traits for which St. Edith is remembered, since she was a noblewoman by birth and a humble person by choice.

Nobility never gets a solo aria; it represents a dynamic and creative force which prefers to enter into dialogue with the other characters in the three duets she has to sing (one of which is precisely with Edith). This does not imply for Nobility to be a minor character: rather, her duets are masterpieces of rhetoric and her arguments are those Edith finds hardest to counter. The musical personality and role of Nobility are balanced by those of Humility, who in fact eschews the lights of the stage and intervenes as if framing the Oratorio with her wisdom. Among the memorable moments of this Oratorio are in fact one of the duets (Bella luce del Ciel che difende, sung by Edith and Nobility: here the proximity between the two characters is evident), and the ending. This is prepared by a charming trio (indicated as “chorus” in the libretto) by the three high-pitched “qualities” who seem finally convinced by Edith’s arguments. The true conclusion, however, is entrusted to Humility, who closes the Oratorio according to her style and personality, with two lines of a simple recitativo, which brings to light the spiritual meaning of the entire work. In her words, citing from the Biblical King David (in turn a saint and a sovereign), “He that goeth forth and weepeth, bearing precious seed, shall doubtless come again with rejoicing, bringing his sheaves with him”.

The entire Oratorio, therefore, struggles with and beautifully demonstrates the double-sidedness of many human feelings, aspirations and desires. Similar to Edith, who chose sanctity and chastity while continuing to love beauty and elegance, and similar to the qualities, whose arguments are frequently sensible and reasonable, though ultimately discarded by the princess, the music joins gorgeous melodic lines, magnificent melismas and intense dialogues before finding its ending in absolute simplicity.

Even though Stradella’s Oratorios have reattained fame only in relatively recent years, these features continued to fascinate their early listeners years after the composer’s death (and this is particularly remarkable at a time when all music was contemporary by definition). After the premiere, the Oratorio was in fact performed twice more in Modena, in 1684 and in 1692, thus bearing witness to Stradella’s enduring fame after his death. The extant manuscript score for the Oratorio, found in Modena, was probably prepared for these performances. This Da Vinci Classics album, therefore, gives voice – quite literally – to this magnificent score, and to the fascinating personality of its protagonist.

01. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Aria: "Il premio felice"" (Humiltà)

02. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "De' miei veri consigli"" (Humiltà)

03. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Aria: "Speranze gradite"" (Santa Editta)

04. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Codarda, e che, vaneggio?"" (Santa Editta)

05. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Duetto: "A che giova il regnar"" (Grandezza, Nobiltà)

06. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "O del ciel saggi detti"" (Santa Editta)

07. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Aria: "Se l'arciero lusinghiero"" (Santa Editta)

08. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "D'un tuo servo fedel" - Aria: "Dunque il ciel tanti contenti"" (Santa Editta)

09. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Quei diporti che in dono"" (Santa Editta)

10. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Aria: "Così fuggite"" (Santa Editta)

11. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Di chi brama il tuo ben" - Aria: "Chi pianti e sospiri"" (Bellezza)

12. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Pregio che poco dura" - Aria: "Che piacer non di si dee"" (Santa Editta)

13. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Aria: "Bellezze rapine"" (Santa Editta)

14. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Senza offendere il giusto"" (Grandezza)

15. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Terzetto: "O come si mira sovente"" (Nobiltà, Grandezza, Senso)

16. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Se vago in oriente"" (Santa Editta)

17. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Aria: "Piagge amene"" (Santa Editta)

18. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Tua ragion non comprendo"" (Grandezza, Humiltà)

19. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Duetto: "Chi può le nostr'alme"" (Grandezza, Humiltà)

20. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Fra le porpore e gli ostri" - Aria: "Su, su, cingetemi"" (Santa Editta)

21. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Con non più intesi accenti"" (Bellezza, Santa Editta, Senso)

22. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Aria: "A punir le colpe un'alma"" (Senso)

23. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Alle vigilie intenti"" (Grandezza, Santa Editta, Nobiltà, Bellezza)

24. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Terzetto: "Mal nato é il desire"" (Nobiltà, Grandezza, Bellezza)

25. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Della vita mortal nel breve giorno"" (Santa Editta)

26. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Dite su, pompe che siete?"" (Santa Editta)

27. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Duetto: "Siamo scorta a voi mortali"" (Nobiltà, Grandezza)

28. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Aria: "Spesso un regio ambito soglio"" (Grandezza)

29. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Dite su, piacer, che siete?"" (Santa Editta)

30. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Duetto: "Noi sirene siamo all'alme"" (Grandezza, Senso)

31. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Aria: "Chi i suoi lumi al vostro canto" - Recitativo: "Dite su, piacer, che siete?"" (Senso, Santa Editta)

32. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Terzetto: "Noi sirene siamo all'alme"" (Nobiltà, Grandezza, Senso)

33. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Dunque la reggia abbandonar t'aggrada?"" (Senso, Santa Editta, Nobiltà)

34. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra: "Duetto "Bella luce del ciel"" (Santa Editta)

35. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Agi, pompe, beltà, dilette e regni"" (Santa Editta)

36. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Aria: "Così disciolta da cure frali"" (Santa Editta)

37. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Arresta un sol momento"" (Bellezza, Santa Editta)

38. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Aria: "L'orme stampi veloci il piè"" (Santa Editta)

39. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Qui tace la reina"" (Grandezza)

40. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Terzetto: "A notte breve"" (Nobiltà, Grandezza, Bellezza)

41. Santa Editta, Vergine e Monaca, Regina d'Inghilterra, "Recitativo: "Di profeta real s'odan gli accenti"" (Humiltà)

Those familiar with art history are likely to know the figure of Michelangelo Merisi, aka Caravaggio, not only for his magnificent paintings, iconic of the early Baroque style, but also for the mysterious circumstances of his violent death. His paintings, both in the sacred and in the secular sphere, still fascinate and charm thanks to their depth, to their chiaroscuro, and to the inextricable intertwining of ecstasy, holiness and sensuous overtones. Much of the above could apply both to the biography and to the output of Alessandro Stradella, another major artist of the Italian Baroque, though one whose masterpieces are found in the domain of the sounds instead of the colours.

Stradella had an adventurous life, whose coups de théâtre have elicited the interest and curiosity of many biographers, librettists and composers in the following centuries. He was successful with women, and his story is a tale of elopements, hurried escapes from jealous husbands or brothers, failed attempts to kill him and – eventually – an aggression leading to his death.

Even though these adventures belong very much in the sphere of the secular, as a composer Stradella was equally successful and appreciated as a creator of both sacred music and of secular works. Many of his compositions have survived, including several dramas or comedies with music (i.e. the early forms of opera), fragments of similar works, a very high number of secular and sacred cantatas, as well as instrumental music (including Sonatas and Concerto-like forms).

He also composed at least eight Oratorios – a genre which was still relatively recent at his time –, most of which embody the ideals and value of the Catholic Reformation after Trent. Music was seen by many Catholic Reformers as a touching and efficacious way to instill religious feelings, ideals and virtues. These early Oratorios therefore could be based on Biblical stories (thus favouring a personal and emotional response to the Scriptural narrative), on the lives of saints or martyrs, or on moralising subjects, with virtues and vices being frequently personified by the characters on stage.

The most common subjects were, predictably, the protagonists of Biblical episodes which possessed a particularly strong dramatic power (such as Judith and Holofernes, or Jephthah’s daughter, to name but two of the most frequently chosen), or, among the saints, the most famous ones and (even more importantly) those whose feast-day required a special and solemn celebration.

To be sure, St. Edith would not have qualified in any of the preceding categories. She was an English princess whose short life blossomed just before the year 1000. St. Edith’s mother, Wilfrida, a noblewoman, had been a nun at Wilton Abbey, but was abducted by Edgar, king of England (who was known, ironically, by the title of “Peaceful”). Edgar did penance for his crime by not wearing his crown for seven years; Edith was born, and, of course, was destined to become the wife of a man of royal descent. However, Wilfrida did not remain at Edgar’s side for long: approximately one year after Edith’s birth, she went back to the monastery with her child, was elected abbess and entrusted her daughter to the nuns who took care of her education (along with that of other noble girls). As reported by Edith’s biographer, the monk Goscelin, the girl used to dress sumptuously, in spite of her intense religiosity; she maintained that “pride could exist under the garb of wretchedness, but a mind could be pure under rich vestments”. Actually, under her mother Wilfrida’s rule, the nuns wore white robes embroidered in gold, “to the glory of God”. When her time came to choose her vocation, Edith preferred to remain in the monastery, renouncing the splendour of a queen’s life; she died very young, and was renowned for her wisdom, knowledge, beauty and holiness.

Her feast-day was celebrated on September 16th, and a seventeenth-century Italian hagiography narrates her story as follows: “St. Edith, the daughter of Edgar King of England, preferred the humility of Christ’s Cross to her father’s kingdom’s pomp and to the vanity of worldly greatness. […] Having become a nun, she greatly loved the holy humility, exercising works of Christian piety and serving the other nuns in their humblest needs. She refused, due to humility, the title of Abbess, choosing to be the least of all rather than to rule the others” (Delle vite de’ santi d’ogni mese, Bologna, 1675).

It clearly appears from these lines that humility was the trait for which Edith was most praised; it is not therefore by chance that a character by the name of Humility is found in Stradella’s Oratorio, contending with other qualities (such as Greatness, Nobility, Sensuality and Beauty) for the young princess’ heart. In fact, even though the story of St. Edith is not devoid of dramatic interest and could provide an intriguing libretto, the Oratorio by Stradella hardly narrates any episode of the saint’s biography. Rather, it stages the interior struggle of the protagonist, who is drawn to monastic life but who has to listen to the advice of these personified qualities. They in fact attempt to convince her to take the crown instead of the veil.

St. Edith is therefore the only real, human character on stage. This confers to her person a particularly powerful aura, and draws the audience’s attention on her feelings and personality. While the other singers represent “just” disembodied qualities, she is the only human being whose heart may encompass different, and sometimes conflicting, feelings.

Thus, once more the question arises: why does an English saint who lived more than six hundred years earlier and who was not the object of particular devotion in Italy become the protagonist of an Oratorio?

The most likely answer is also rather puzzling. It has been argued that the (unknown) occasion for the creation and premiere of Santa Editta may have been the wedding, in 1673, of Maria Beatrice d’Este, a fifteen-years old noblewoman, with James Stuart, who was forty-one and was the heir to the English throne. There was nothing strange in the idea of celebrating an aristocratic wedding with an oratorio; moreover, James’ nationality could encourage the librettist to find a subject related with English sacred history. As happened to virtually all aristocratic weddings of the time, the marriage had been combined for political reasons: King Louis XIV of France, in the midst of the confessional turmoil following the Reformations, wanted a Catholic couple on the English throne, and was supported by the Pope.

Similar to St. Edith, however, the intended bride was personally inclined to become a nun; similar to St. Edith’s mother, moreover, the bride’s mother, Laura Martinozzi, favoured her daughter’s wishes. When, however, the Pope himself wrote a letter to Maria Beatrice requesting her consent to the marriage with James, the two women could not refuse anymore.

On the one hand, then, it is understandable that an Oratorio about a holy English princess could celebrate the wedding of an Italian girl to an English prince. On the other, however, it strikes us as entirely inappropriate that the story of a nun who was allowed to choose the veil instead of the crown should celebrate the wedding of another girl who would have preferred to have the same power to choose.

Moreover, as we have seen, St. Edith was famous for her humility, but her appreciation of the royal garments did not entirely conform to the stereotype of a humble nun. This ambivalence is also found in the Oratorio: perhaps not in the libretto, created by the nobleman Lelio Orsini (c. 1623-1696), a prince from Latium, but certainly in the music written by Stradella.

In fact, the protagonist sings numerous arias, encompassing a wide range of moods, styles and affections. In comparison with other coeval saints, the chronicle by Goscelin tells us much about the character of this young saint, who comes to life not as a bidimensional portrait but rather as a real woman (we even learn that she had several pet animals, and that one of her miracles involved rescuing her chest of dresses from a fire!). And even though the libretto’s words are much less lively, the music supplies the drama and vivacity surrounding the protagonist’s figure.

St. Edith’s refreshing and youthful personality is in fact portrayed in some of her arias, sparkling with fantasy and exuberance. This is the case, for example, with Speranze gradite, in a joyful triple time evoking dance steps and with virtuoso passages of great musical appeal. Even more dazzling is Se l’arciero lusinghiero, where the piercing and flying arrows are very graphically depicted through dazzling scales. The protagonist’s primacy, however, is masterfully balanced by the interventions of the other singers.

Similar to the other known oratorios by Stradella, in fact, Santa Editta is sung in Italian and is divided into two parts. Even though there are six characters, the Oratorio requires only five singers (once more, as in the other similar works by the composer), since one singer may interpret two roles.

There is a clear correspondence between the vocal ranges and the “personality” of the characters embodying the qualities who speak with Edith. The most sensuous and earthly character, Sensuality, is sung by a bass, whose low voice seems to associate him to the basest passions. He is the first character to appear in the Oratorio after the two positive personae (St. Edith and Humility); his arguments are also those which Edith can counter more easily. He is also the first to disappear from the Oratorio, whereas Beauty, Greatness and Nobility remain until the very end.

Beauty is in turn a “material” quality, but it is endowed with a higher status, since Beauty is also a quality of the Godhead. It is therefore symbolized by a tenor voice, possibly suggesting the beauty of a young male lover (as happens in most operas). Greatness is interpreted by a contralto, a voice whose range is halfway through the entire compass of the human voice. In fact, a love for greatness may encourage both holiness and depravity: it can lead to a life of virtue or to a lust for power. The two remaining characters are sung by a soprano, thus showing that Nobility and Humility can coexist. In fact, these are the two traits for which St. Edith is remembered, since she was a noblewoman by birth and a humble person by choice.

Nobility never gets a solo aria; it represents a dynamic and creative force which prefers to enter into dialogue with the other characters in the three duets she has to sing (one of which is precisely with Edith). This does not imply for Nobility to be a minor character: rather, her duets are masterpieces of rhetoric and her arguments are those Edith finds hardest to counter. The musical personality and role of Nobility are balanced by those of Humility, who in fact eschews the lights of the stage and intervenes as if framing the Oratorio with her wisdom. Among the memorable moments of this Oratorio are in fact one of the duets (Bella luce del Ciel che difende, sung by Edith and Nobility: here the proximity between the two characters is evident), and the ending. This is prepared by a charming trio (indicated as “chorus” in the libretto) by the three high-pitched “qualities” who seem finally convinced by Edith’s arguments. The true conclusion, however, is entrusted to Humility, who closes the Oratorio according to her style and personality, with two lines of a simple recitativo, which brings to light the spiritual meaning of the entire work. In her words, citing from the Biblical King David (in turn a saint and a sovereign), “He that goeth forth and weepeth, bearing precious seed, shall doubtless come again with rejoicing, bringing his sheaves with him”.

The entire Oratorio, therefore, struggles with and beautifully demonstrates the double-sidedness of many human feelings, aspirations and desires. Similar to Edith, who chose sanctity and chastity while continuing to love beauty and elegance, and similar to the qualities, whose arguments are frequently sensible and reasonable, though ultimately discarded by the princess, the music joins gorgeous melodic lines, magnificent melismas and intense dialogues before finding its ending in absolute simplicity.

Even though Stradella’s Oratorios have reattained fame only in relatively recent years, these features continued to fascinate their early listeners years after the composer’s death (and this is particularly remarkable at a time when all music was contemporary by definition). After the premiere, the Oratorio was in fact performed twice more in Modena, in 1684 and in 1692, thus bearing witness to Stradella’s enduring fame after his death. The extant manuscript score for the Oratorio, found in Modena, was probably prepared for these performances. This Da Vinci Classics album, therefore, gives voice – quite literally – to this magnificent score, and to the fascinating personality of its protagonist.

Year 2021 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads