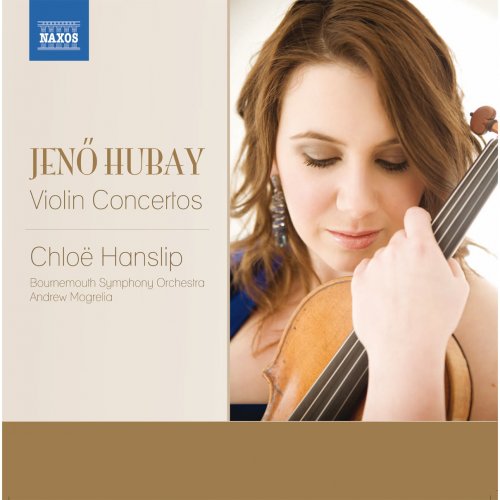

Chloë Hanslip - Jenö Hubay: Violin Concertos (2009)

BAND/ARTIST: Chloë Hanslip

- Title: Jenö Hubay: Violin Concertos

- Year Of Release: 2009

- Label: Naxos

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:10:40

- Total Size: 351 Mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor, Op. 21 "Concerto dramatique" (Jenö Hubay)

1. I. Allegro appassionato 11:39

2. II. Adagio ma non tanto 10:57

3. III. Allegro con brio 07:54

Scenes de la Csarda No. 3, Op. 18, 'Maros vize' (version for violin and orchestra) (Jenö Hubay)

4. Scènes de la Csárda No. 3, Op. 18 "Maros vize" (Version for Violin & Orchestra) 07:14

Scenes de la Csarda No. 4, Op. 32, 'Hejre Kati' (Hey, Katie) (version for violin and orchestra) (Jenö Hubay)

5. Scènes de la Csárda No. 4, Op. 32 "Hejre Kati" (Version for Violin & Orchestra) 06:18

Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major, Op. 90 (Jenö Hubay)

6. I. Allegro con fuoco 11:08

7. II. Larghetto 09:12

8. III. Allegro non troppo 06:18

Performers:

Chloë Hanslip (Violin)

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: Andrew Mogrelia

Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor, Op. 21 "Concerto dramatique" (Jenö Hubay)

1. I. Allegro appassionato 11:39

2. II. Adagio ma non tanto 10:57

3. III. Allegro con brio 07:54

Scenes de la Csarda No. 3, Op. 18, 'Maros vize' (version for violin and orchestra) (Jenö Hubay)

4. Scènes de la Csárda No. 3, Op. 18 "Maros vize" (Version for Violin & Orchestra) 07:14

Scenes de la Csarda No. 4, Op. 32, 'Hejre Kati' (Hey, Katie) (version for violin and orchestra) (Jenö Hubay)

5. Scènes de la Csárda No. 4, Op. 32 "Hejre Kati" (Version for Violin & Orchestra) 06:18

Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major, Op. 90 (Jenö Hubay)

6. I. Allegro con fuoco 11:08

7. II. Larghetto 09:12

8. III. Allegro non troppo 06:18

Performers:

Chloë Hanslip (Violin)

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: Andrew Mogrelia

The music of Jen? Hubay has experienced a sort of renaissance, perhaps related to the sesquicentennial of his birth in 1858. Teacher of Joseph Szigeti and a large number of other violinists at the turn of the century (Franz von Vecsey, Georg Kulenkampff, Tibor Varga, Zoltán Szekely, André Gertler, and Stefi Geyer, among them), he achieved a sort of first wave of renown, although Carl Flesch maintained that if he had been able to teach Szigeti himself, he might have solved his technical problems. He may have played Beethoven’s “Kreutzer” Sonata with Liszt, but he didn’t adapt his compositional style in the 20th century to the emerging way of collecting authentic folk materials and incorporating them explored by Zoltán Kodály and Béla Bartók; and his star perhaps faded considerably on account of his relative conservatism.

The first two concertos employ all the virtuosic techniques inherited by Vieuxtemps from Paganini, filtered through the prism of Bériot’s musical sensibilities. His orchestration, like that of Vieuxtemps, who entrusted his last concerto to Hubay for completion, sound Romantically symphonic, though his imposing tuttis add a harmonic spice and sense of modulatory freedom at which Vieuxtemps’s stately compositions hardly hint. All together, these elements add up to a sense of bigness with which a violinist must sympathize in order to lend credibility to performances of Hubay’s works. Chloë Hanslip plays the First Concerto (“Dramatique”) with the requisite virtuosity in the first and third movements, and with idiomatic warmth in those movements’ lyrical sections—as well as throughout the second movement. If she and the orchestra don’t quite achieve coherence in the second movement, that may be due as much to the movement’s greater desultory sense than to any lack of understanding on her part or on the part of Mogrelia. In the finale, Mogrelia generates a sense of nostalgia that suits Hubay’s harmonic schemes like a glove.

Ferenc Szecsödi and István Kassai (Hungaroton 32060, 28:6) and Hagai Shaham (Hyperion 67441/2, reviewed by me in 28:6 and by Paul Ingram in 28:1) have recorded the Third and Fourth of the Scènes de la csárda with piano, but Charles Castleman played them with the Eastman Chamber Orchestra on Music & Arts 1164, 28:6, which also includes a number of Hubay’s students and Hubay himself, playing his music. Hanslip seems temperamentally suited to their ethnic style and format, typical declamatory Gypsy rhapsody giving way in both cases to a dance-like second section. She’s dark, richly expressive, and brightly virtuosic as required. Hubay’s own recordings (which can be sampled on the Music & Arts CD previously mentioned, as well as on Testament 1313) reveal a lighter touch in the passagework than those accustomed to the greater intensity of the Russian school may have come to expect. (An examination of Hubay’s bowing studies, Six Études, op. 63—which, incidentally, he stretched over very similar harmonic frameworks—may offer insight into his approach to passagework, and violinists might profitably make their way through them before approaching his concert works.)

The Second Concerto, composed almost a generation after the First, offers a mixture of the struttingly heroic with the meltingly lyrical (especially in the atmospheric slow movement), very like that which Hubay had served up in his first essay in the genre—and very like that which he would showcase again in his Third Concerto—though with an even stronger expressivity (and perhaps a greater cohesiveness). Hanslip easily meets the climatic challenges of this arguably warmer temperature.

The engineers have placed their soloist far enough within the orchestral matrix to achieve the kind of balance a listener might experience in a live performance, while still capturing the warmth of her sound, whatever loss of the sharpest detail such a strategy might imply. Mogrelia and the orchestra match Hanslip’s sympathetic understanding of Hubay’s sense of days gone by, and perhaps places far away. (Hagai Shaham played these concertos with Martyn Brabbins and the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra on Hyperion 67498, 30:1; but Naxos’s engineers lit the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra more brightly, and Hanslip plays for the most part with a more poignant Romantic sensibility.) Warmly recommended to those who wish to explore these concertos or to those unfamilar with Hubay’s works for violin and orchestra. -- Robert Maxham

The first two concertos employ all the virtuosic techniques inherited by Vieuxtemps from Paganini, filtered through the prism of Bériot’s musical sensibilities. His orchestration, like that of Vieuxtemps, who entrusted his last concerto to Hubay for completion, sound Romantically symphonic, though his imposing tuttis add a harmonic spice and sense of modulatory freedom at which Vieuxtemps’s stately compositions hardly hint. All together, these elements add up to a sense of bigness with which a violinist must sympathize in order to lend credibility to performances of Hubay’s works. Chloë Hanslip plays the First Concerto (“Dramatique”) with the requisite virtuosity in the first and third movements, and with idiomatic warmth in those movements’ lyrical sections—as well as throughout the second movement. If she and the orchestra don’t quite achieve coherence in the second movement, that may be due as much to the movement’s greater desultory sense than to any lack of understanding on her part or on the part of Mogrelia. In the finale, Mogrelia generates a sense of nostalgia that suits Hubay’s harmonic schemes like a glove.

Ferenc Szecsödi and István Kassai (Hungaroton 32060, 28:6) and Hagai Shaham (Hyperion 67441/2, reviewed by me in 28:6 and by Paul Ingram in 28:1) have recorded the Third and Fourth of the Scènes de la csárda with piano, but Charles Castleman played them with the Eastman Chamber Orchestra on Music & Arts 1164, 28:6, which also includes a number of Hubay’s students and Hubay himself, playing his music. Hanslip seems temperamentally suited to their ethnic style and format, typical declamatory Gypsy rhapsody giving way in both cases to a dance-like second section. She’s dark, richly expressive, and brightly virtuosic as required. Hubay’s own recordings (which can be sampled on the Music & Arts CD previously mentioned, as well as on Testament 1313) reveal a lighter touch in the passagework than those accustomed to the greater intensity of the Russian school may have come to expect. (An examination of Hubay’s bowing studies, Six Études, op. 63—which, incidentally, he stretched over very similar harmonic frameworks—may offer insight into his approach to passagework, and violinists might profitably make their way through them before approaching his concert works.)

The Second Concerto, composed almost a generation after the First, offers a mixture of the struttingly heroic with the meltingly lyrical (especially in the atmospheric slow movement), very like that which Hubay had served up in his first essay in the genre—and very like that which he would showcase again in his Third Concerto—though with an even stronger expressivity (and perhaps a greater cohesiveness). Hanslip easily meets the climatic challenges of this arguably warmer temperature.

The engineers have placed their soloist far enough within the orchestral matrix to achieve the kind of balance a listener might experience in a live performance, while still capturing the warmth of her sound, whatever loss of the sharpest detail such a strategy might imply. Mogrelia and the orchestra match Hanslip’s sympathetic understanding of Hubay’s sense of days gone by, and perhaps places far away. (Hagai Shaham played these concertos with Martyn Brabbins and the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra on Hyperion 67498, 30:1; but Naxos’s engineers lit the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra more brightly, and Hanslip plays for the most part with a more poignant Romantic sensibility.) Warmly recommended to those who wish to explore these concertos or to those unfamilar with Hubay’s works for violin and orchestra. -- Robert Maxham

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads