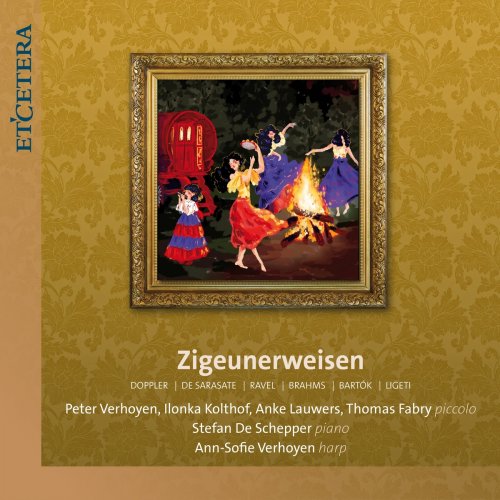

Stefan De Schepper - Zigeunerweisen (2020)

BAND/ARTIST: Stefan De Schepper

- Title: Zigeunerweisen

- Year Of Release: 2020

- Label: Etcetera

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 50:55 min

- Total Size: 222 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

01. Fantaisie Pastorale Hongroise

02. Zigeunerweisen (1878)

03. Tzigane (1924)

04. Csárdás (1904)

05. Hungarian Dance Nr. 5 (1879)

06. Hungarian Dance Nr. 6 (1879)

07. Duos (1931) - Ugyan Édes Komámasszony (Teasing Song)

08. Duos (1931) - Burleszk (Burlesque)

09. Duos (1931) - Magyar Nóta (Hungarian Song)

10. Duos (1931) - Szól a Duda (Bagpipes)

11. Duos (1931) - Arab Dal (Arabischer Gesang)

12. Balada (1950)

13. Romanian Dances - Jocul Cu Bâta (Stick Dance)

14. Romanian Dances - Brâul (Sash Dance)

15. Romanian Dances - Pe Loc (In One Spot)

16. Romanian Dances - Buciumeana (Dance from Bucsum)

17. Romanian Dances - Poarga Româneasca (Romanian Polka)

18. Romanian Dances - Ma Runt El (Fast Dance)

01. Fantaisie Pastorale Hongroise

02. Zigeunerweisen (1878)

03. Tzigane (1924)

04. Csárdás (1904)

05. Hungarian Dance Nr. 5 (1879)

06. Hungarian Dance Nr. 6 (1879)

07. Duos (1931) - Ugyan Édes Komámasszony (Teasing Song)

08. Duos (1931) - Burleszk (Burlesque)

09. Duos (1931) - Magyar Nóta (Hungarian Song)

10. Duos (1931) - Szól a Duda (Bagpipes)

11. Duos (1931) - Arab Dal (Arabischer Gesang)

12. Balada (1950)

13. Romanian Dances - Jocul Cu Bâta (Stick Dance)

14. Romanian Dances - Brâul (Sash Dance)

15. Romanian Dances - Pe Loc (In One Spot)

16. Romanian Dances - Buciumeana (Dance from Bucsum)

17. Romanian Dances - Poarga Româneasca (Romanian Polka)

18. Romanian Dances - Ma Runt El (Fast Dance)

Béla Bartók at a meeting of the Hungarian Ethnographic Society, 29 April 1931 When Bartók opened his lecture entitled Gypsy music? Hungarian music? with this controversial statement, he lit the fuse of a discussion that had been raging since the middle of the 19th century. The central question of this discussion was the indistinct and ever-changing boundary between the Hungarian musical legacy and Roma music. Some seventy years earlier, Franz Liszt had revived the debate with his book Des Bohémiens et de leur musique en Hongrie (1859), in which he stated that such a boundary was an illusion: there was no Hungarian folk music that was not gypsy music. By Bartók’s time, however, the discussion had become much more complex: the Hungarian music heritage had in the meantime inspired a new national style whose authenticity had come to be questioned. What, exactly, had served as its model? Original folk music or a non-historical variant that had grown with the Roma tradition? Gypsy music? Hungarian music?

The Hungarian question is just one example of the problems with which a notion such as gypsy music struggles, simply because the “gypsy” is not a historical reality but a false generalisation. When the Roma migrated from India to Persia and then spread throughout Europe during the Middle Ages, they swiftly formed sub-groups, each of which had its own cultural identity. While the communities took care to preserve their separate identities, they also adopted traditions from their host countries, as can be seen in the diversity of their musical practices. For example, the Irish Roma repertoire is linked to the folk song tradition, Spanish Roma have their own type of flamenco and the bagpipes play a leading role in Scottish Roma music. Gypsy music takes many forms, but some characteristics nonetheless rise above the various traditions, such as the use of rhapsodic structures with striking tempo changes, a quasi-improvisatory style of writing and rubato performance. Also seen as characteristic are strongly accentuated and syncopated rhythms, long pauses and sustained tones, modal twists and rich ornamentation. Roma music, being full of temperament, capricious, asymmetrical and unpredictable, seems to go against every expectation. This musical representation of a culture that refuses to accommodate itself to Western norms intrigued composers more and more as the 19th century advanced.

The Hungarian question is just one example of the problems with which a notion such as gypsy music struggles, simply because the “gypsy” is not a historical reality but a false generalisation. When the Roma migrated from India to Persia and then spread throughout Europe during the Middle Ages, they swiftly formed sub-groups, each of which had its own cultural identity. While the communities took care to preserve their separate identities, they also adopted traditions from their host countries, as can be seen in the diversity of their musical practices. For example, the Irish Roma repertoire is linked to the folk song tradition, Spanish Roma have their own type of flamenco and the bagpipes play a leading role in Scottish Roma music. Gypsy music takes many forms, but some characteristics nonetheless rise above the various traditions, such as the use of rhapsodic structures with striking tempo changes, a quasi-improvisatory style of writing and rubato performance. Also seen as characteristic are strongly accentuated and syncopated rhythms, long pauses and sustained tones, modal twists and rich ornamentation. Roma music, being full of temperament, capricious, asymmetrical and unpredictable, seems to go against every expectation. This musical representation of a culture that refuses to accommodate itself to Western norms intrigued composers more and more as the 19th century advanced.

Year 2020 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads