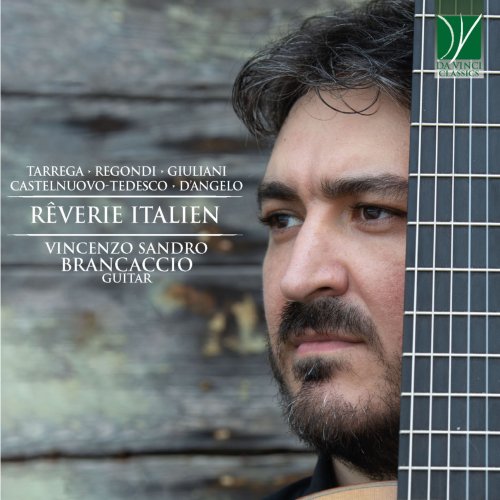

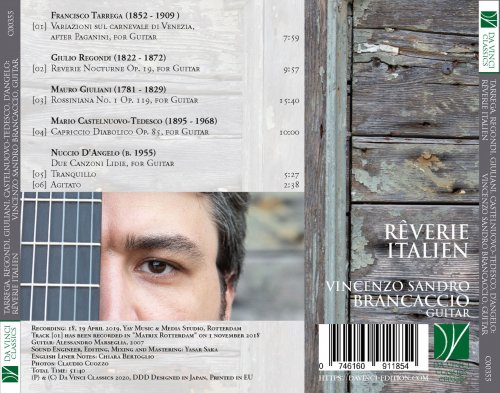

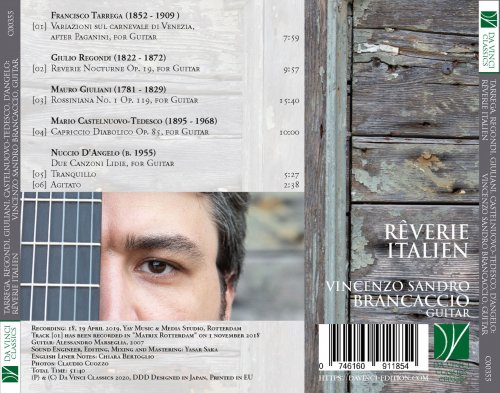

Vincenzo Sandro Brancaccio - Tarrega, Regondi, Giuliani, Castelnuovo-Tedesco, D'Angelo: Rêverie Italien (2021)

BAND/ARTIST: Vincenzo Sandro Brancaccio

- Title: Tarrega, Regondi, Giuliani, Castelnuovo-Tedesco, D'Angelo: Rêverie Italien

- Year Of Release: 2021

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical Guitar

- Quality: flac lossless

- Total Time: 00:51:41

- Total Size: 163 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Variazioni sul carnevale di Venezia, after Paganini in A Major

02. Reverie-Nocturne, Op. 19

03. Rossiniana No. 1, Op. 119

04. Capriccio Diabolico, Op. 85a

05. Due Canzoni Lidie: No. 1, Tranquillo

06. Due Canzoni Lidie: No. 2, Agitato

The guitar is an instrument which stands apart from most others. It does not normally belong in the symphonic orchestra, and it is only occasionally called for in the chamber music works written by the major mainstream classical composers. It is an instrument which frequently enjoys its golden isolation, and which prides itself of being autonomous, thanks to its capability both to sustain a tune with expressiveness, and to provide it with a full harmonization.

In its solo repertoire, in fact, the guitar manages to express two seemingly opposing features: a vocation to singing, and one to virtuosity. Typically, an expressive singer necessitates an adequate accompaniment, but also needs to feel free to adjust the rhythmical frame to the requirements of musical expression: when both tune and accompaniment are performed by the same musician (as happens in the works for solo guitar), expressive freedom is at its highest.

Similarly, virtuosity is the technical mastery of an instrument to the point that a musician is able to follow his or her inspiration on the spur of the moment, being capable to realize almost effortlessly every musical idea which may come to his or her mind.

Here too the advantage of being “alone” is clear: solo musicians do not need to communicate their musical intentions beforehand, either verbally or performatively, and are not constrained by the necessities of ensemble music-making, as satisfying this may be as a musical experience.

Thus, these two souls of the solo instrument have always been observed by musician writing for solo guitar, and are perfectly represented in this Da Vinci Classics album.

The works recorded here pay homage to the Italian musical tradition, embodied by some of its most iconic representatives. Cantabile and virtuosity constantly intertwine with each other, in the tunes which emerge from within a dense technical pattern, or in the variations which decorate a beautiful tune, clinging on its notes like ivy leaves around an architectural structure.

The first example of this attitude is represented by Tárrega’s variations on a very famous tune, indicated in the score as having been written by Paganini. As a matter of fact, Paganini himself had borrowed a much earlier tune, written probably towards the end of the 1740s by an otherwise unknown Italian musician, by the name of Giovanni Cifolelli. The tune was woven into a country-dance which became widely known as “La Cifolella”; it reached many European countries finding new names in the various places (including the German Mein Hut, der hat drei Ecken), and eventually becoming famous as the “Carnival of Venice”.

Niccolò Paganini, who is known even beyond the borders of classical music as the prototype of the virtuoso violinist, wrote a series of variations on this tune, substantially contributing to its fame; he was followed by Johann Kaspar Mertz, a virtuoso Austro-Hungarian guitarist, whose op. 6 is in turn a version of this celebrated melody for the guitar.

It was probably Mertz who inspired Tárrega to write his own set of variations, which employ a great variety of technical resources and find the most fascinating sound effects which are available on the guitar. In spite of the instrumental difficulty, the charming tune ensures a pleasant and agreeable result, which delights the listener even in the midst of the most complex technical passages.

The figure of Paganini, which had inspired a new culture of instrumental virtuosity – not just on the violin, as pianists such as Schumann and Liszt could testify – had probably also influenced the early life of Giulio Regondi (1822-1872), an unjustly forgotten Italian composer. Regondi had been educated by an ambitious father who exploited his son’s musical gifts by having him perform as a child prodigy on the European stages. At the age of nine, he was abandoned by his father and managed to make a living in London; ten years later, he resumed his activity as a touring musician, but his interest for the guitar decreased progressively, replaced by a growing passion for the concertina, similar to a small accordion.

In spite of this, one of his best-known pieces was written for the guitar, and it is precisely the Revêrie Nocturne op. 19 recorded here. While the title might suggest a slow, reflective piece, Regondi manages to blend virtuosity with cantabile: the beat is in fact rather slow, the tunes are wide and extended, but in between the melody’s notes there is an abundance of decorations and virtuoso accompaniments, turning this work almost into a catalogue of technical difficulties.

One year before Regondi’s birth, another Italian guitarist, Mauro Giuliani, was embarking in the first of a series of six Rossiniane, which would quickly obtain high acclaim and wide popularity. Rossini’s tunes were being sung in the opera theatres, but also on the concert stage, in the homes and sometimes in the streets; the amiability and brilliancy of these melodies never failed to conquer the ears and hearts of their listeners.

Similar to what happens today with the medleys of popular songs or tunes, the nineteenth-century pot-pourris imaginatively combined melodies from a variety of provenances, combining them in a kind of musical patchwork which was both entertaining and satisfying. In the first Rossiniana by Giuliani, the melodies by Rossini are excerpted from the tragedy of Otello (an aria by Desdemona, “Assisa a piè d’un salice”), from the sparkling comical vein of L’Italiana in Algeri and from the more serious tones of Armida.

In fact, Giuliani was a friend of both Rossini and Paganini, and his versions of Rossini’s tunes do not simply exploit the fame of the operas, but rather represent an artistic appropriation of the operatic language. Writing to the publisher Giulio Ricordi, Giuliani affirmed that Rossini had “favoured me with many originals from which I can arrange everything that appeals to me”; the three of them liked to spend time together, making music and enjoying each other’s company.

With his usual humour, indeed, Rossini affirmed that he had cried only twice in his entire life: one was when a turkey stuffed with truffles accidentally fell in a pool, and the other was when he heard Paganini playing.

The figure of Paganini is also observed behind Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s Capriccio diabolico. Castelnuovo-Tedesco was commissioned this work by one of the greatest guitarists of all times, i.e. Andrés Segovia, who explicitly intended the work as a homage to Paganini. Whilst Paganini was also a celebrated guitar virtuoso, his fame is closely bound to his works for violin, and most particularly to the transcendental 24 Capriccios. Paganini’s technical skills were so impressive that a diabolic legend started to surround him, and this superhuman – though devilish – halo is evoked also in the title of Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s work.

Different from Giuliani’s homage to Rossini, woven with recognizable tunes from the operas, here the homage is more implicit, referring to the virtuosity of Paganini’s style only obliquely. The only explicit reference is a quote from a Concerto by Paganini, known as La Campanella. Unfortunately, however, this work sadly brought some enmity between its dedicatee and its composer, who allegedly was not satisfied with Segovia’s interpretation and therefore reworked the piece into a version for guitar and orchestra.

This programme is completed by a contemporary work by Nuccio D’Angelo, a living Italian guitarist and composer. His Due Canzoni Lidie is one of his best known works, in spite of being also one of his earliest. In the composer’s own words, these Two Lydian Songs are inspired by an “imaginary place, where memories of ancient melos and archaic modal forms” are found. The music narrates of a “traveller who discovers the fascination of a primeval forgotten world”. The use of the traditional Lydian mode leads the composer to a “strict respect” for their rules, but also to a special and intense expressiveness. The two pieces, in their own special fashion, demonstrate in turn the two souls of the guitar, its singing and its more virtuoso quality. The first piece, Tranquillo, is – according to the composer – “a free Divertimento” constituted by “several recurring thematic phrases”, while the second, Agitato, is a Fantasy “characterized and structured by the continuing use of a cell of three notes”, as well as by an intense “use of chromaticism”, causing a “more troubling atmosphere”.

This musical itinerary, thus, has shown a net of retrospective and forward-looking gazes, of implicit and explicit homages, of cultural influences: Paganini citing Cifolelli, and being cited by Tárrega and by Castelnuovo-Tedesco; his friend Giuliani citing Rossini and its operas; D’Angelo citing the ancient modes and the enchanted wisdom they transmit, in a pattern which transcends both history and geography but revolves around Italy, around Paganini, and around the guitar.

01. Variazioni sul carnevale di Venezia, after Paganini in A Major

02. Reverie-Nocturne, Op. 19

03. Rossiniana No. 1, Op. 119

04. Capriccio Diabolico, Op. 85a

05. Due Canzoni Lidie: No. 1, Tranquillo

06. Due Canzoni Lidie: No. 2, Agitato

The guitar is an instrument which stands apart from most others. It does not normally belong in the symphonic orchestra, and it is only occasionally called for in the chamber music works written by the major mainstream classical composers. It is an instrument which frequently enjoys its golden isolation, and which prides itself of being autonomous, thanks to its capability both to sustain a tune with expressiveness, and to provide it with a full harmonization.

In its solo repertoire, in fact, the guitar manages to express two seemingly opposing features: a vocation to singing, and one to virtuosity. Typically, an expressive singer necessitates an adequate accompaniment, but also needs to feel free to adjust the rhythmical frame to the requirements of musical expression: when both tune and accompaniment are performed by the same musician (as happens in the works for solo guitar), expressive freedom is at its highest.

Similarly, virtuosity is the technical mastery of an instrument to the point that a musician is able to follow his or her inspiration on the spur of the moment, being capable to realize almost effortlessly every musical idea which may come to his or her mind.

Here too the advantage of being “alone” is clear: solo musicians do not need to communicate their musical intentions beforehand, either verbally or performatively, and are not constrained by the necessities of ensemble music-making, as satisfying this may be as a musical experience.

Thus, these two souls of the solo instrument have always been observed by musician writing for solo guitar, and are perfectly represented in this Da Vinci Classics album.

The works recorded here pay homage to the Italian musical tradition, embodied by some of its most iconic representatives. Cantabile and virtuosity constantly intertwine with each other, in the tunes which emerge from within a dense technical pattern, or in the variations which decorate a beautiful tune, clinging on its notes like ivy leaves around an architectural structure.

The first example of this attitude is represented by Tárrega’s variations on a very famous tune, indicated in the score as having been written by Paganini. As a matter of fact, Paganini himself had borrowed a much earlier tune, written probably towards the end of the 1740s by an otherwise unknown Italian musician, by the name of Giovanni Cifolelli. The tune was woven into a country-dance which became widely known as “La Cifolella”; it reached many European countries finding new names in the various places (including the German Mein Hut, der hat drei Ecken), and eventually becoming famous as the “Carnival of Venice”.

Niccolò Paganini, who is known even beyond the borders of classical music as the prototype of the virtuoso violinist, wrote a series of variations on this tune, substantially contributing to its fame; he was followed by Johann Kaspar Mertz, a virtuoso Austro-Hungarian guitarist, whose op. 6 is in turn a version of this celebrated melody for the guitar.

It was probably Mertz who inspired Tárrega to write his own set of variations, which employ a great variety of technical resources and find the most fascinating sound effects which are available on the guitar. In spite of the instrumental difficulty, the charming tune ensures a pleasant and agreeable result, which delights the listener even in the midst of the most complex technical passages.

The figure of Paganini, which had inspired a new culture of instrumental virtuosity – not just on the violin, as pianists such as Schumann and Liszt could testify – had probably also influenced the early life of Giulio Regondi (1822-1872), an unjustly forgotten Italian composer. Regondi had been educated by an ambitious father who exploited his son’s musical gifts by having him perform as a child prodigy on the European stages. At the age of nine, he was abandoned by his father and managed to make a living in London; ten years later, he resumed his activity as a touring musician, but his interest for the guitar decreased progressively, replaced by a growing passion for the concertina, similar to a small accordion.

In spite of this, one of his best-known pieces was written for the guitar, and it is precisely the Revêrie Nocturne op. 19 recorded here. While the title might suggest a slow, reflective piece, Regondi manages to blend virtuosity with cantabile: the beat is in fact rather slow, the tunes are wide and extended, but in between the melody’s notes there is an abundance of decorations and virtuoso accompaniments, turning this work almost into a catalogue of technical difficulties.

One year before Regondi’s birth, another Italian guitarist, Mauro Giuliani, was embarking in the first of a series of six Rossiniane, which would quickly obtain high acclaim and wide popularity. Rossini’s tunes were being sung in the opera theatres, but also on the concert stage, in the homes and sometimes in the streets; the amiability and brilliancy of these melodies never failed to conquer the ears and hearts of their listeners.

Similar to what happens today with the medleys of popular songs or tunes, the nineteenth-century pot-pourris imaginatively combined melodies from a variety of provenances, combining them in a kind of musical patchwork which was both entertaining and satisfying. In the first Rossiniana by Giuliani, the melodies by Rossini are excerpted from the tragedy of Otello (an aria by Desdemona, “Assisa a piè d’un salice”), from the sparkling comical vein of L’Italiana in Algeri and from the more serious tones of Armida.

In fact, Giuliani was a friend of both Rossini and Paganini, and his versions of Rossini’s tunes do not simply exploit the fame of the operas, but rather represent an artistic appropriation of the operatic language. Writing to the publisher Giulio Ricordi, Giuliani affirmed that Rossini had “favoured me with many originals from which I can arrange everything that appeals to me”; the three of them liked to spend time together, making music and enjoying each other’s company.

With his usual humour, indeed, Rossini affirmed that he had cried only twice in his entire life: one was when a turkey stuffed with truffles accidentally fell in a pool, and the other was when he heard Paganini playing.

The figure of Paganini is also observed behind Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s Capriccio diabolico. Castelnuovo-Tedesco was commissioned this work by one of the greatest guitarists of all times, i.e. Andrés Segovia, who explicitly intended the work as a homage to Paganini. Whilst Paganini was also a celebrated guitar virtuoso, his fame is closely bound to his works for violin, and most particularly to the transcendental 24 Capriccios. Paganini’s technical skills were so impressive that a diabolic legend started to surround him, and this superhuman – though devilish – halo is evoked also in the title of Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s work.

Different from Giuliani’s homage to Rossini, woven with recognizable tunes from the operas, here the homage is more implicit, referring to the virtuosity of Paganini’s style only obliquely. The only explicit reference is a quote from a Concerto by Paganini, known as La Campanella. Unfortunately, however, this work sadly brought some enmity between its dedicatee and its composer, who allegedly was not satisfied with Segovia’s interpretation and therefore reworked the piece into a version for guitar and orchestra.

This programme is completed by a contemporary work by Nuccio D’Angelo, a living Italian guitarist and composer. His Due Canzoni Lidie is one of his best known works, in spite of being also one of his earliest. In the composer’s own words, these Two Lydian Songs are inspired by an “imaginary place, where memories of ancient melos and archaic modal forms” are found. The music narrates of a “traveller who discovers the fascination of a primeval forgotten world”. The use of the traditional Lydian mode leads the composer to a “strict respect” for their rules, but also to a special and intense expressiveness. The two pieces, in their own special fashion, demonstrate in turn the two souls of the guitar, its singing and its more virtuoso quality. The first piece, Tranquillo, is – according to the composer – “a free Divertimento” constituted by “several recurring thematic phrases”, while the second, Agitato, is a Fantasy “characterized and structured by the continuing use of a cell of three notes”, as well as by an intense “use of chromaticism”, causing a “more troubling atmosphere”.

This musical itinerary, thus, has shown a net of retrospective and forward-looking gazes, of implicit and explicit homages, of cultural influences: Paganini citing Cifolelli, and being cited by Tárrega and by Castelnuovo-Tedesco; his friend Giuliani citing Rossini and its operas; D’Angelo citing the ancient modes and the enchanted wisdom they transmit, in a pattern which transcends both history and geography but revolves around Italy, around Paganini, and around the guitar.

Year 2021 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads