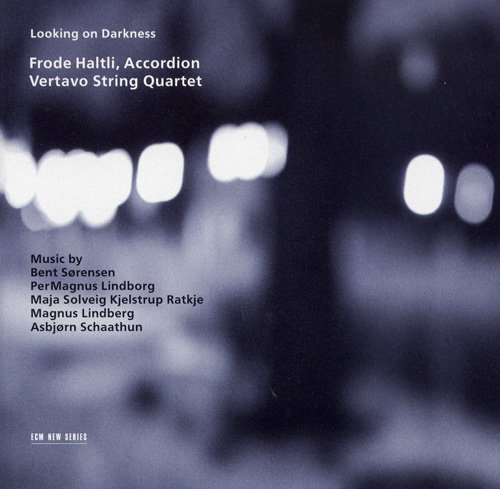

Frode Haltli - Looking On Darkness (2002)

BAND/ARTIST: Frode Haltli

- Title: Looking On Darkness

- Year Of Release: 2002

- Label: ECM

- Genre: Contemporary, Classical, Modern Composition

- Quality: FLAC (tracks+.cue, log)

- Total Time: 1:00:27

- Total Size: 294 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

01. Looking on Darkness (10:01)

02. Bombastic SonoSofisms (8:47)

03. Gagaku Variations (23:49)

04. Jeux d'anches (8:22)

05. Lament (9:27)

01. Looking on Darkness (10:01)

02. Bombastic SonoSofisms (8:47)

03. Gagaku Variations (23:49)

04. Jeux d'anches (8:22)

05. Lament (9:27)

Much like its bellowed cousins, the accordion’s mystique lies in its duality. With one hand the chords are laid, with the other a melody is wrought. Yet just as easily those roles may switch, intermingling in a constant process of renegotiation. Although they share the same breath, pushed and pulled through the same lungs, there is always a separation between the two, so that when they are brought together in a program like this, they seem to unfold, one division after another, into a greater unity. This refraction of audible intent renders any introspection attempted by the musician a moot endeavor, seeking instead a window of opportunity in which to curl one’s fingers about the contours of an unspoken promise. In this way the accordion becomes a psychological instrument, providing more insight into its handler than psychoanalysis ever could. Through this window we can see that Frode Haltli’s is a mind of depth, conviction, in service to the music he plays. For his first solo album, the young Norwegian puts his bellows to four solo compositions and one for chamber ensemble.

First, the solos.

Bent Sørensen’s title study in decay is the perfect place to open our ears. It eases us into an uneasy sound-world, where light is darkness and the vocal becomes instrumental. The result sits somewhere between a declamatory statement and an uncertain question. From this we are awakened to different shades of vulnerability. Haltli shows no fear in exposing these snatches of tenderness, proving just how delicate a line he walks.

PerMagnus Lindborg’s abiding interest in all things electronic shines through in his Bombastic Sonosofisms. The sound is more pointillist here, and seems to peer into even darker recesses of the psyche. While it does require some astounding virtuosity, a shimmering, cosmic veneer obscures any possible wow factor that might get in the way of the listening. Where Sørensen drew in arcs, Lindborg favors the erratic, nesting us in a field of right angles.

Take away the “Per” and you are left with Finnish composer Magnus Lindberg and his Jeux d’anches. This piece thrives on identity crises and rhythmic leaps, gathering into its purview a life unfulfilled yet resigned. It is a puzzle unfolding piece by piece, only each is of uniform shape and size. In such great numbers, however, one is baffled to put them together. Haltli accomplishes the daunting task of forming a cogent picture out of them all.

Asbjørn Schaathun’s Lament explores the accordion more than any of its companions. From growling low notes to piercing highs, it surrounds a turgid middle ground. It is a church organ being born, coming into self-awareness as the music marks its slow passage through muddy terrain. Notes coincide, double, and fragment, seemingly unable to strike out on their own and achieve true independence. In the end, they are bound by air.

Then there is the program’s centerpiece, the gagaku variations of Maja Solveig Kjelstrup Ratkje, which pairs the accordion’s fullness with another: the string quartet. In this configuration, violins melt into Haltli’s richer sound like ghosts hidden in between its folds. The contrast between brief pizzicato passages and the more sinuous notes of the accordion cut through the very tensions they define. Some probing questions from the high strings bring our focus away from the sky and back to the soil, and in the end paint us with their own language. If this were a play, we would be the ones on stage, and the performers would be watching, waiting for us to speak.

The accordion is not an instrument one is used to hearing in a classical setting, and yet here it blossoms without generic borders. In Haltli’s hands, it attains a level of depth rarely heard. His performances are bold and detailed, as if he were holding a magnifying glass to a newspaper photograph in an attempt to show us the dots and blank spaces it is made of. The album’s title tells us all: rather than looking into darkness, we are looking on it, for the naked eye will never uncover the core of that which is infinite.

First, the solos.

Bent Sørensen’s title study in decay is the perfect place to open our ears. It eases us into an uneasy sound-world, where light is darkness and the vocal becomes instrumental. The result sits somewhere between a declamatory statement and an uncertain question. From this we are awakened to different shades of vulnerability. Haltli shows no fear in exposing these snatches of tenderness, proving just how delicate a line he walks.

PerMagnus Lindborg’s abiding interest in all things electronic shines through in his Bombastic Sonosofisms. The sound is more pointillist here, and seems to peer into even darker recesses of the psyche. While it does require some astounding virtuosity, a shimmering, cosmic veneer obscures any possible wow factor that might get in the way of the listening. Where Sørensen drew in arcs, Lindborg favors the erratic, nesting us in a field of right angles.

Take away the “Per” and you are left with Finnish composer Magnus Lindberg and his Jeux d’anches. This piece thrives on identity crises and rhythmic leaps, gathering into its purview a life unfulfilled yet resigned. It is a puzzle unfolding piece by piece, only each is of uniform shape and size. In such great numbers, however, one is baffled to put them together. Haltli accomplishes the daunting task of forming a cogent picture out of them all.

Asbjørn Schaathun’s Lament explores the accordion more than any of its companions. From growling low notes to piercing highs, it surrounds a turgid middle ground. It is a church organ being born, coming into self-awareness as the music marks its slow passage through muddy terrain. Notes coincide, double, and fragment, seemingly unable to strike out on their own and achieve true independence. In the end, they are bound by air.

Then there is the program’s centerpiece, the gagaku variations of Maja Solveig Kjelstrup Ratkje, which pairs the accordion’s fullness with another: the string quartet. In this configuration, violins melt into Haltli’s richer sound like ghosts hidden in between its folds. The contrast between brief pizzicato passages and the more sinuous notes of the accordion cut through the very tensions they define. Some probing questions from the high strings bring our focus away from the sky and back to the soil, and in the end paint us with their own language. If this were a play, we would be the ones on stage, and the performers would be watching, waiting for us to speak.

The accordion is not an instrument one is used to hearing in a classical setting, and yet here it blossoms without generic borders. In Haltli’s hands, it attains a level of depth rarely heard. His performances are bold and detailed, as if he were holding a magnifying glass to a newspaper photograph in an attempt to show us the dots and blank spaces it is made of. The album’s title tells us all: rather than looking into darkness, we are looking on it, for the naked eye will never uncover the core of that which is infinite.

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads