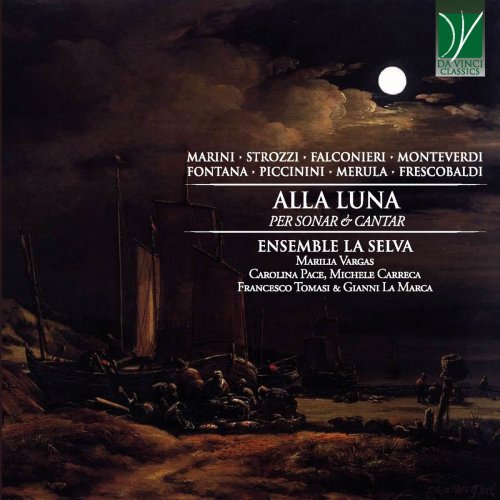

“Alla Luna”, “To the Moon”. Gazing to the moon and letting one’s mind wander has been the birth and inspiration of a poetic sentiment and feeling for countless human beings throughout history and geography. Precisely because of the undeniable charm of the Moon and of her power to awaken the poet who lies asleep in most human breasts, only the greatest poets have been able to leave truly enchanting verses about her. We may recall Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice (1605): “The moon shines bright, in such a night as this. When the sweet wind did gently kiss the trees and they did make no noise, in such a night”. Or, in the Far East, another seventeenth-century poet, Matsuo Bashō: “Oh! the moon gazing where some clouds / From time to time repose the eye!”.

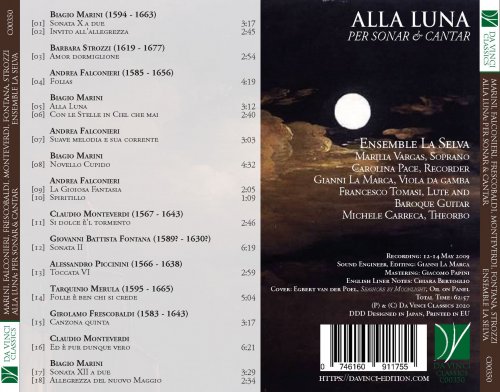

Or, in another of his haiku: “How much I desire! Inside my little satchel, the moon, and flowers”. In sharp contrast with these exquisite verbal watercolours, in the same century as Shakespeare and Bashō an Italian poet, by the name of Claudio Achillini, defined the moon as “the great omelette in the pan of the sky”. The lyrics set to music by Biagio Marini in the song lending its name to this Da Vinci Classics album are somewhat midway between the sublimity of Shakespeare and Bashō and the puzzling creativity of Achillini. Here the moon is “silvery” (not a very original adjective, to be sure, when applied to the moon), and is defined as the Sun’s “darker sister”; with an allusion to a Biblical quote (from Song of Songs), her “darkness / does not detract from her beauty”. If the lyrics possibly will not qualify among the most memorable definitions of the Moon in the history of literature, the music by Biagio Marini works wonders, and transforms a series of little more than platitudes into pure magic. The “poems”, which, in the lyricist’s words, are the “arms conquering” Night, “that mother of shadows and fears”, become, in Marini’s hands, a garland of notes descending to the depths of the voice’s texture, and thus representing both the aesthetic fascination and the dangerous charm of the Moon and of Night. This album collects a series of vocal and instrumental works by several Italian musicians of the early Baroque era; the choice of putting Alla Luna at center stage is very appropriate, since this short masterpiece epitomizes many qualities found also in the other works. There is an exquisite balance between words and music, between the needs of the recently created “recitar cantando” and those of virtuosity, a trait much sought-for by Baroque composers and listeners alike. There is a close interaction between vocality and the instrumental component: even the purely instrumental pieces recorded here display their indebtedness to the world of singing and to the vocal aesthetics of the Baroque period. The emergence of a strong harmonic feeling is clearly observable, but, at the same time, the interplay between the melodic lines is elegant and reveals the composers’ familiarity with polyphonic writing. And, finally, by listening to this and to the other pieces in this album, we gain an “aural glimpse” over a lost world, a society whose written and unwritten rules are difficult to imagine today, but whose artistic refinement was paralleled only by its adventurous lifestyle. For example, Falconieri fled Parma and abandoned his employ overnight, giving no reasons, and later was the protagonist of a minor scandal in Genoa due to his (musical) frequentations of female convents; Biagio Marini was married thrice, and left his first wife before embarking in a very turbulent life punctuated by a series of jobs in many Italian and European cities; and, last but not least, Barbara Strozzi was an enormously gifted woman but not exactly the prototype of the housewife.

The biographies of most of the composers represented here are in fact rather impressive; when one counts their journeys (and the miles they travelled), their conjugal and extra-conjugal adventures, and sometimes the number of children they had, one wonders how they managed to find time for writing such beautiful music.

Biagio Marini was one of the finest violinists of his era, and it is therefore no wonder that he left an abundant and extraordinary output of instrumental music. Similar to many of his colleagues represented here, he was a very precocious artist, and his first published works were probably composed in his teens and published when he was barely twenty years old. At that time, he was working as a violinist in Venice, where he had been employed as a member of the orchestra of St Mark’s, led by Claudio Monteverdi. Undoubtedly, Marini’s early exposure to the genius and innovations of the great composer proved to be fundamental for his later development. Monteverdi was in fact creating and establishing a new musical language, crafted upon the tendencies of the late sixteenth-century and upon an even older tradition, but which was gaining acceptance in the world of “refined” music only in the early decades of the seventeenth century. Monteverdi’s own Ed è pur dunque vero, recorded here, is a typical example: less pathetic than most of his madrigals, but poignant in its comparative lightness, it employs the human voice as the most ductile and expressive of all instruments.

Indeed, the boundary between the instrumental and the vocal is really thin in most pieces recorded here; formulae from the palette of instrumental virtuosity are adopted by the voice, and others from the vocal repertoire transition to the instrumental domain.

The quest for pleasure and joy, and the desire for wonder and amazement typical for the Baroque aesthetics (and which was also behind the awkward metaphors by Achillini) are found also in other of the Scherzi e canzonette by Marini, such as, for example, Invito a l’Allegrezza, where both lyrics and music concur to the creation of a sparkling atmosphere of happiness and levity. The search for an inventio which was both “quest” and “fantasy” is also found in exquisitely instrumental pieces, such as the Folias by Falconieri, another musician and composer who lived in many European countries (including Spain, where the Folias theme took the courts by storm) and who contributed to the development of the new instrumental language; here, virtuoso elements create a thrilling dialogue between the two upper parts, which occasionally seem to play hide-and-seek and which cooperate to the creation of a brilliant concluding climax. Similarly, Falconieri’s La suave melodia, an enormously successful tune, is expressively nuanced and characterized by a noble pacing; unsurprisingly, it is acknowledged to be one of his greatest works. Similar to Marini, also Giovanni Battista Fontana was known to his contemporaries both as a violinist and as a composer; in particular, the preface to the posthumous publication of his collection of Sonatas praises him as “one of the most singular [i.e. exceptional] virtuosos on the Violin of his age”, and this is clearly revealed by his daring style and refined handling of both the compositional structures and the details of instrumental technique. Garlands of notes testify to his sprezzatura, his capability to face virtuoso passages with seeming ease and total mastery.

A similar virtuosity, though in the vocal field, characterized also the only female composer represented here, Barbara Strozzi; she was a Venetian courtesan of exceptional culture, independence and free-mindedness, who managed to gain acceptance into the highest circles of the contemporaneous aristocracy and in those of the most acclaimed artists and composers of her era. She even founded a private Academy of her own, of which she quickly became the soul and the inspiration. Interestingly, she also managed to be an excellent mother of four (three of her children eventually entered holy orders or the cloister). Alessandro Piccinini was in turn an appreciated virtuoso, but his field of specialization were the plucked-string instruments; he was a member of a family of musicians, and, when in Rome, he created an exceptional ensemble with Frescobaldi, the great organist, and three female singers. Frescobaldi’s own Canzona, performed here, is an iconic symbol for his artistry and aesthetics; its name reveals how closely intertwined were the worlds of instrumental and vocal music, and yet the idiom is already exquisitely instrumental. Similar to Frescobaldi, also Tarquinio Merula was a highly appreciated organist, who was in high demand both in Italy and abroad (in Poland). His output includes both sacred and secular music, and, in both fields, he managed to find a voice of his own, a personal and original style appreciated by his contemporaries and by present-day listeners.

Together, these seven composers represent the extreme vivacity and liveliness of the Italian cultural life of their era, its open-mindedness and capacity to acquire and transform the musical languages of many European countries, while exporting the “Italian” sound throughout the Continent. They offer us a perspective on the development of novel styles, which were observed and experimented with in the genuine pleasure and playfulness of the new discoveries. They also reveal how musical forms which were deemed as minor or less serious with respect to church music and to the “high” madrigal culture of the era managed to find a profundity and depth of their own, in aesthetic and spiritual terms. They invite us to contemplate “the Moon”, i.e. the source of poetical and musical inspiration, with that same enchanted and inspired gaze they had, and to discover the awe and amazement so typical for the Baroque era.

Album Notes by Chiara Bertoglio