The advantage of playing the piano is that the performer has slightly less than a full orchestra under his or her fingers: chords of up to ten notes (and even more) can be simultaneously played, a great timbral variety may be achieved by virtue of touch, articulation and pedalling, and a single musician may achieve musical results which compare more easily with a symphonic orchestra than with any other instrument. The disadvantage is that the privilege of solitude may become the pianist’s doom, and the life of a virtuoso solo pianist may consist of many solitary hours.

While this may appeal to some, for many others, including numerous amateur pianists, the pleasure of making music would be increased by the possibility of sharing the experience with others. Moreover, and particularly at a time when the mechanical or digital reproduction of sound was not yet available or common, orchestral works were frequently transcribed for piano duo: this allowed a more faithful transcription of the thickest orchestral textures, and, at the same time, permitted the enjoyment of the orchestral masterpieces by both the players and their listeners. Finally, in the pedagogical field, the possibility of having two budding pianists playing together offered multiple advantages: together, they could play works of a greater complexity than those they could have played alone; they could also refine their sense of rhythm and tempo; they learnt to adopt listening habits which would prove fundamental both for solo and for ensemble music-making.

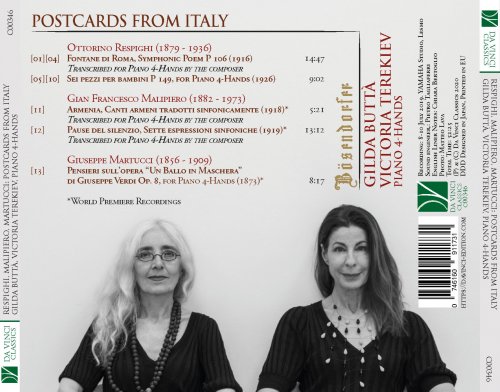

This Da Vinci Classics album offers a fascinating overview comprising works for four-hand piano duo written by the so-called “1880 Generation”, in the words of the great music critic Massimo Mila. Under this label, Mila grouped four composers who were born within the space of four years, 1879-1883, namely Ottorino Respighi, Ildebrando Pizzetti, Alfredo Casella and Gian Francesco Malipiero. The task for which they are collectively best remembered is their effort to reconstruct the Italian musical heritage of the past (particularly of the Renaissance and Baroque era), not only in an antiquarian view but aiming at the revivification of these works on the concert stage; moreover, their knowledge of the past inspired these four musicians, each in his own way, to craft a modern idiom whose antique roots could be clearly visible.

The paths of their lives took different turns; occasionally, harsh polemics (frequently with political overtones, especially at the time of Fascism) divided them. Their aesthetical perspectives became pronouncedly at variance; yet, Mila’s definition stands the test of time, because there are common elements uniting these four musicians along the mere biographical data.

Indeed, even though Casella and Respighi stood sometimes on the opposing sides of an aesthetical divide, Casella wanted a particular picture to be reproduced in his autobiography, I segreti della Giara. The photograph portrays both of them, seated side by side on the bench of a Welte-Mignon mechanical piano, and performing together the transcription of Respighi’s Fontane di Roma.

Among the four, Respighi was certainly the most successful, and the one whose fame lasts internationally to present-day. This fame is due especially to his cycle of three symphonic poems, dedicated to the Fountains, the Pine-Trees and the Feasts of the city of Rome, and are the creative consequence of his first impressions of the Eternal City, to which he had recently moved. Respighi had demonstrated his musical gifts since his student years, and had perfected his musical education with experiences abroad, both as a performer and as a composer. He had learnt the secrets of the orchestra from the inside, playing first viola in the St. Petersburg Symphonic Orchestra; while in Russia, he had had the opportunity of studying instrumentation with the musician who was probably the greatest orchestrator of all times, Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov. These experiences provided Respighi with an absolute mastery of the orchestral colours, and a particular sensitivity for the timbral combinations. This, together with his undeniable musical fantasy and capability to “portray” situations in music, contributed to the success of the Roman Trilogy.

Composed in 1916, Fontane di Roma was performed the following year at one of the most important Italian venues, the Teatro Augusteo; however, the premiere was very disappointing, and Respighi had renounced all dreams of glory for his work. Unexpectedly, when in 1918 the piece was performed once more at La Scala in Milan under Toscanini’s baton, it met with thunderous applause and undisputed success, bringing its composer to international acclaim.

The piece’s four movements, seamlessly connected to each other, depict as many of the Roman fountains “in the hour where their character harmonizes most with the surrounding landscape, or when their beauty seems the most suggestive to those contemplating them”. Therefore, the first movement depicts the Fountain of Valle Giulia at dawn, surrounded by a quiet and bucolic atmosphere of natural and pastoral peace; the second portrays the Fountain of the Tritone in the morning, and evokes a festive pageant of mythical inhabitants of the sea, whose horns resound throughout the movement. The sea-god Neptune is found also in the third movement, where the Fountain of Trevi at midday becomes the scenery for the triumph of the pagan gods. The last piece alludes to the Fountain of Villa Medici at sunset; here the Baroque fantasies evoked by the luxuriant sculptures of mythical beings disappear, and nature, with the aural symbols of a Christian society, emerges once more.

If, as Respighi maintained, the “light” of the different hours was so crucial for showing the true beauty of each fountain – or, in aural terms, if his masterful orchestration is such a fundamental component of the pieces – how will the work result in a piano transcription? The composer himself and his great colleague Casella seemed to appreciate the four-hands version and to consider it on a par with the orchestral original; certainly, the challenge of transforming the piano into an orchestra is not to be taken lightly, but, in the hands of great pianists, this transcription reveals a profound beauty of its own.

By way of contrast, the Sei pezzi per bambini by Respighi are deceivingly simple; conceived originally for piano duo, they offer to their performers a musical tour of the globe, touching Sicily, Scotland and – interestingly – Armenia. Written in 1926, they represent a delightful collection of miniatures, portraying situations (such as Christmas, seen with children’s eyes) and people, and, especially, playing with modality and exoticism in order to transcend the trivial diatonicism of many pieces for children.

If Respighi’s “Armenian” piece explored the possibilities of small-range melodies, creating a hypnotic serpentine of sound, the same idea inspires the beginning of Gian Francesco Malipiero’s Armenia, a series of songs “symphonically transcribed” by the Venetian master. In fact, the work exists in several original versions, dating around 1918, and including one for violin and piano, one for orchestra, and the present one. The tunes are skillfully combined, and the piece reaches heights of expressiveness, melancholia and nostalgia but also of vivacity and rhythmical power.

One year later, when the First World War had only recently ended, Malipiero completed another symphonic work presented here in the version for piano duet, the Pause del silenzio. The pieces’ connection with the war is not simply chronological: in the composer’s words, they “reflect my agitated state” during wartime. While no extramusical content is declared, their title refers to the importance of silence in a moment when war made it “most difficult to find silence. Precisely because of their tumultuous origins, they contain no thematic development or other artifices”. Notwithstanding this, each of the seven pieces has an “expression”, an affection of its own: a pastoral (echoing Respighi’s first movement), a scherzo-like dance, a serenade with lugubrious overtones, a tumultuous whirl, a funereal elegy, a fanfare and a “fire of violent rhythms”. The silence to which the pieces pay homage is broken by the authoritative opening gesture, which recurs as a leitmotiv between the sections: in Malipiero’s words, “it is somewhat heroic, because a timid voice would not be likely to interrupt the silence”. Premiered in 1918 at the Augusteo, this cycle was followed by another by the same title, which did not prove as successful as its elder brother.

This fascinating album focusing on two of the most important musicians of the “Generation of the 1880s” closes with a small forgotten gem, representing the value of the piano duet for the re-presentation of successful music in a family context. Written by Giuseppe Martucci, a great pianist and a pioneer of the ideals which would inspire the “Generation of the 1880s” (indeed, Martucci would later be Respighi’s teacher), it is the work of a 17-years old composer and piano virtuoso who took inspiration from one of the most successful of Verdi’s operas, Un ballo in Maschera, weaving some of its best-loved themes into a characteristic pot-pourri.

From the extreme demands of timbre and technique posed by Respighi’s Fontane and by Malipiero’s Pause del silenzio to the misleading naivety of the children’s pieces, from the compositional experiments of Armenia to the salon atmosphere of Martucci’s piece, this album offers to the listener the full palette of the social and artistic value of the piano duo in the early decades of the twentieth century.

Liner Notes by Chiara Bertoglio