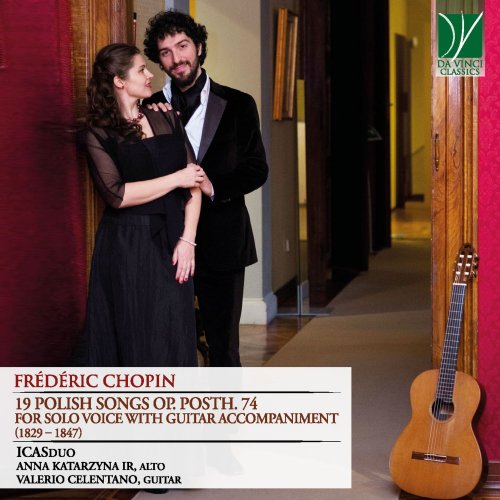

Anna Katarzyna Ir, ICASduo, Valerio Celentano - Frédéric Chopin: 19 Polish Songs Op. posth. 74 (2020)

BAND/ARTIST: Anna Katarzyna Ir, ICASduo, Valerio Celentano

- Title: Frédéric Chopin: 19 Polish Songs Op. posth. 74

- Year Of Release: 2020

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless

- Total Time: 00:45:17

- Total Size: 225 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

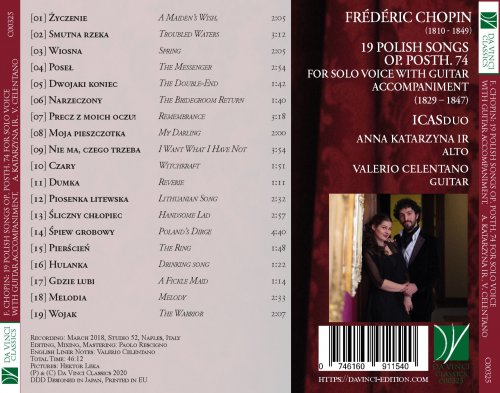

Tracklist

01. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 1, Życzenie (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

02. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 3, Smutna rzeka (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

03. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 2, Wiosna (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

04. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 7, Poseł (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

05. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 11, Dwojaki koniec (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

06. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 15, Narzeczony (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

07. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 6, Precz z moich oczu! (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

08. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 12, Moja pieszczotka (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

09. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 13, Nie ma, czego trzeba (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

10. Polish Songs, Op. 74 (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

11. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 19, Dumka (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

12. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 16, Piosenka litewska (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

13. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 8, Śliczny chłopiec (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

14. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 17, Śpiew z mogiłky (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

15. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 14, Pierścień (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

16. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 4, Hulanka (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

17. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 5, Gdzie lubi (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

18. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 9, Melodia (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

19. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 10, Wojak (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

The 19 Polish Songs for voice and piano by Frédéric Chopin (Żelazowa Wola 1810 – Paris 1849) were composed between the 1829 and the 1847, but were published, as op.74, only ten years after the composer’s death by his friend Juliusz Fontana. They did not arise the musicians interest till the middle of the XXth century, when, finally, great singers began to insert them into their programs. That was possible because of numerous linguistic adaptations (French, German, Italian) prepared by the most important publishers at the end of the XIXth century. The Songs are rare examples of the chamber music compositions and, first of all, they are unique as vocal compositions in the Chopin’s art catalogue. They often were created as a sort of impromptu executions based on the lyrics of some major Polish poets of that period; especially in Parisian salons, during the upper-middle class and aristocracy meetings, these compositions used to be written down as hommages on the important ladies (as Delfina Potocka or Emilia Elsner, for example) albums. The Chopin’s interest for the vocal chamber music was perfectly in line with the European trend of the so-called Salonmusik for which an ad hoc repertoire was destinated. The German Lied, the French mélodie and the Italian romanza raised the vocal artistic level, seconding the already tested and rich repertoire of transcriptions, arrangements and reductions of opera arias that, for some decades, had been responding to the requests of amateurs and swelling the publishers’ pockets. At that time the musicians, once arrived in a new city either for a short stay or for a long period, used to compose pieces designated for the “good” salons, just to introduce themselves to the high society. It is possible that many compositions we are talking about were born according to this cliché, which does not impoverish them of their deep inspiration and artistic value.

Although of different character among them, the Chopin’s songs were united by the constant of the lyrics choice, written, as mentioned, by the greatest Polish poets of the time, poets that entertained correspondence and relationship with the composer even far from his native soil. From the biography written by the famous pianist and composer Ferenc Liszt we know that during the Polish Great Emigration period Chopin frequented in Paris the poets Stefan Witwicki and Bohdan Zaleski and also a circle composed largely of his compatriots, where he had the opportunity to stay up to date on the political and cultural situation in Poland. He was pleased to view new poems and sometimes decided to music them and, still according to Liszt, the new songs seemed to become popular immediately in his homeland, but many times their author’s name remained unknown. That was the way -wrote the Hungarian pianist- he managed to stay in a sort of “musical correspondence” with his faraway land (Liszt in primis will demonstrate a great consideration for the vocal compositions of his friend making an arrangement for piano solo of six songs from the op.74. They will be published as Six Chants polonais S.480). It is therefore very probable that the composed songs were many more than those recovered by Fontana, but already at that time it was impossible to define the real authorship of the ones attributed to him. We know for sure that in 1836, on the occasion of the anniversary of the Polish Constitution, Chopin used the verses of Wincenty Pol to compose ten patriotic-inspired songs in Paris, but nowadays we know only one of them: Leci lisćie z drzewa.

In this CD you won’t find the mazurka in G major Jakież kwiaty, jakie wianki of which we only have notice of the short melodic voice line with lyrics but without any accompaniment and it is not even included in Op. 74 printed edition.

To fulfill the romantic postulate of correspondence des arts and to stay in line with his coeval liederists, Chopin treated the composition of his songs with extreme simplicity, limiting the instrumental parts to very short introductions, interludes and tails, and often drawing, just as he already was doing in his style, from the folklore and rhythms of Polish dances: you can find oberek in Życzenie, galop in Wojak, kujawiak in Pierścien, some Ukrainian rythms in Czary, and in Hulanka, Moja pieszczotka, Śliczny Chłopiec and many others the mazurka pulsations. Chopin’s last pieces are conditioned, on the contrary, by his precarious psycho-physical state and by his awareness of not being able to see his country never again. The songs definitively abandon any sense of lightness and joie de vivre and they fill up with darker, resigned atmospheres built on more refined and essential harmonies. As Fontana said, with Melodya Chopin reached the magnificence of some of his piano solo pieces.

The catalog of the classical guitar repertoire, in its large corpus made of transcriptions, arrangements and adaptations from other instruments, has always enjoyed, since the nineteenth century, the presence of Frédéric Chopin’s name. The confidentiality, expressiveness and profound inspiration of some of his less virtuous pages, namely: less linked to keyboard mechanics, had undoubtedly arisen, in the romantic and late-romantic period guitarists, the interest and desire of bringing to the own repertoire those works that seemed to marry so well with the nature of the guitar. It could simply be a transcription work but also an attempt to take possession of that lyrical, direct and innovative language. In fact, the influence that the Chopin’s way of writing had, for more than a century, on the style of major guitarists/composers such as Regondi, Mertz, Tàrrega and Barrios, is still very clear.

It had been, however, always limited to the solo repertoire only, in both arrangements and original compositions. In fact, there is no edition of Chopin’s Songs adapted for guitar and voice, till today. And that is why, 170 years after the composer’s death, this work is supposed to be the very first guitar and voice arrangement of the Complete Songs.

The use of the guitar rather than a piano was a well-established practice at the Chopin’s time. From the last decades of the eighteenth century, the vocal chamber music consisted mostly of a dense repertoire of opera arias reductions, intended for salons of the upper-middle social class and aristocracy and it contemplated the alternative use of guitar, harp or lyre-guitar, even in printed versions. Héctor Berlioz, in keeping with that trend, arranged for guitar and voice 25 French opera romances and Ferdinando Carulli did the same with some Rossini’s arias. Even when the vocal compositions had moved away from the former harmonic and rhythmic stereotypes of the accompaniment in favor of a higher artistic research and an original production, the guitar was still used as a valid option instead of the piano (that remained, however, the undisputed master of the salons). For example the great guitarist Mauro Giuliani wrote himself a double piano and guitar accompaniment to some of his vocal compositions. We can cite also the story of Franz Schubert’s Lieder in Vienna. The composer accepted the will of Anton Diabelli – a guitarist, pianist, composer and his publisher – to print some of his Lieder with both piano and guitar accompaniment, aware of the market needs and demands. But, as already said, the Chopin’s Songs were supposed to have another faith. And not only the originals but also their guitar arrangements.

This work derives from the collaboration with a Polish singer Anna Katarzyna Ir- who also assisted me in an indispensable way during the lyrics elaboration for the printed version of 19 Polish Songs (Da Vinci Edition DV 21655).

In regard to the guitar part, we tried to keep as much as possible to the original tones, in order to stay very close to the Chopin’s way of writing. At the same time we essayed to enhance the sonic and expressive features of the guitar and its accompaniment quality by replacing, where necessary, the very pianistic passages with the first XIX century guitar ones. We also aimed to find an homogeneous range within which a medium voice could move easily. In a 1978 article, the musicologist Thomas F. Heck was encouraging the guitarists to face better than Diabelli the Schubert’s Lieder transcriptions. He affirmed: “Schubert’s Lieder for guitar… it’s possible!”.

01. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 1, Życzenie (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

02. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 3, Smutna rzeka (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

03. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 2, Wiosna (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

04. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 7, Poseł (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

05. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 11, Dwojaki koniec (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

06. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 15, Narzeczony (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

07. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 6, Precz z moich oczu! (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

08. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 12, Moja pieszczotka (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

09. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 13, Nie ma, czego trzeba (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

10. Polish Songs, Op. 74 (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

11. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 19, Dumka (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

12. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 16, Piosenka litewska (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

13. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 8, Śliczny chłopiec (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

14. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 17, Śpiew z mogiłky (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

15. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 14, Pierścień (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

16. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 4, Hulanka (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

17. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 5, Gdzie lubi (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

18. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 9, Melodia (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

19. Polish Songs, Op. 74: No. 10, Wojak (Arr. for Solo Voice and Guitar)

The 19 Polish Songs for voice and piano by Frédéric Chopin (Żelazowa Wola 1810 – Paris 1849) were composed between the 1829 and the 1847, but were published, as op.74, only ten years after the composer’s death by his friend Juliusz Fontana. They did not arise the musicians interest till the middle of the XXth century, when, finally, great singers began to insert them into their programs. That was possible because of numerous linguistic adaptations (French, German, Italian) prepared by the most important publishers at the end of the XIXth century. The Songs are rare examples of the chamber music compositions and, first of all, they are unique as vocal compositions in the Chopin’s art catalogue. They often were created as a sort of impromptu executions based on the lyrics of some major Polish poets of that period; especially in Parisian salons, during the upper-middle class and aristocracy meetings, these compositions used to be written down as hommages on the important ladies (as Delfina Potocka or Emilia Elsner, for example) albums. The Chopin’s interest for the vocal chamber music was perfectly in line with the European trend of the so-called Salonmusik for which an ad hoc repertoire was destinated. The German Lied, the French mélodie and the Italian romanza raised the vocal artistic level, seconding the already tested and rich repertoire of transcriptions, arrangements and reductions of opera arias that, for some decades, had been responding to the requests of amateurs and swelling the publishers’ pockets. At that time the musicians, once arrived in a new city either for a short stay or for a long period, used to compose pieces designated for the “good” salons, just to introduce themselves to the high society. It is possible that many compositions we are talking about were born according to this cliché, which does not impoverish them of their deep inspiration and artistic value.

Although of different character among them, the Chopin’s songs were united by the constant of the lyrics choice, written, as mentioned, by the greatest Polish poets of the time, poets that entertained correspondence and relationship with the composer even far from his native soil. From the biography written by the famous pianist and composer Ferenc Liszt we know that during the Polish Great Emigration period Chopin frequented in Paris the poets Stefan Witwicki and Bohdan Zaleski and also a circle composed largely of his compatriots, where he had the opportunity to stay up to date on the political and cultural situation in Poland. He was pleased to view new poems and sometimes decided to music them and, still according to Liszt, the new songs seemed to become popular immediately in his homeland, but many times their author’s name remained unknown. That was the way -wrote the Hungarian pianist- he managed to stay in a sort of “musical correspondence” with his faraway land (Liszt in primis will demonstrate a great consideration for the vocal compositions of his friend making an arrangement for piano solo of six songs from the op.74. They will be published as Six Chants polonais S.480). It is therefore very probable that the composed songs were many more than those recovered by Fontana, but already at that time it was impossible to define the real authorship of the ones attributed to him. We know for sure that in 1836, on the occasion of the anniversary of the Polish Constitution, Chopin used the verses of Wincenty Pol to compose ten patriotic-inspired songs in Paris, but nowadays we know only one of them: Leci lisćie z drzewa.

In this CD you won’t find the mazurka in G major Jakież kwiaty, jakie wianki of which we only have notice of the short melodic voice line with lyrics but without any accompaniment and it is not even included in Op. 74 printed edition.

To fulfill the romantic postulate of correspondence des arts and to stay in line with his coeval liederists, Chopin treated the composition of his songs with extreme simplicity, limiting the instrumental parts to very short introductions, interludes and tails, and often drawing, just as he already was doing in his style, from the folklore and rhythms of Polish dances: you can find oberek in Życzenie, galop in Wojak, kujawiak in Pierścien, some Ukrainian rythms in Czary, and in Hulanka, Moja pieszczotka, Śliczny Chłopiec and many others the mazurka pulsations. Chopin’s last pieces are conditioned, on the contrary, by his precarious psycho-physical state and by his awareness of not being able to see his country never again. The songs definitively abandon any sense of lightness and joie de vivre and they fill up with darker, resigned atmospheres built on more refined and essential harmonies. As Fontana said, with Melodya Chopin reached the magnificence of some of his piano solo pieces.

The catalog of the classical guitar repertoire, in its large corpus made of transcriptions, arrangements and adaptations from other instruments, has always enjoyed, since the nineteenth century, the presence of Frédéric Chopin’s name. The confidentiality, expressiveness and profound inspiration of some of his less virtuous pages, namely: less linked to keyboard mechanics, had undoubtedly arisen, in the romantic and late-romantic period guitarists, the interest and desire of bringing to the own repertoire those works that seemed to marry so well with the nature of the guitar. It could simply be a transcription work but also an attempt to take possession of that lyrical, direct and innovative language. In fact, the influence that the Chopin’s way of writing had, for more than a century, on the style of major guitarists/composers such as Regondi, Mertz, Tàrrega and Barrios, is still very clear.

It had been, however, always limited to the solo repertoire only, in both arrangements and original compositions. In fact, there is no edition of Chopin’s Songs adapted for guitar and voice, till today. And that is why, 170 years after the composer’s death, this work is supposed to be the very first guitar and voice arrangement of the Complete Songs.

The use of the guitar rather than a piano was a well-established practice at the Chopin’s time. From the last decades of the eighteenth century, the vocal chamber music consisted mostly of a dense repertoire of opera arias reductions, intended for salons of the upper-middle social class and aristocracy and it contemplated the alternative use of guitar, harp or lyre-guitar, even in printed versions. Héctor Berlioz, in keeping with that trend, arranged for guitar and voice 25 French opera romances and Ferdinando Carulli did the same with some Rossini’s arias. Even when the vocal compositions had moved away from the former harmonic and rhythmic stereotypes of the accompaniment in favor of a higher artistic research and an original production, the guitar was still used as a valid option instead of the piano (that remained, however, the undisputed master of the salons). For example the great guitarist Mauro Giuliani wrote himself a double piano and guitar accompaniment to some of his vocal compositions. We can cite also the story of Franz Schubert’s Lieder in Vienna. The composer accepted the will of Anton Diabelli – a guitarist, pianist, composer and his publisher – to print some of his Lieder with both piano and guitar accompaniment, aware of the market needs and demands. But, as already said, the Chopin’s Songs were supposed to have another faith. And not only the originals but also their guitar arrangements.

This work derives from the collaboration with a Polish singer Anna Katarzyna Ir- who also assisted me in an indispensable way during the lyrics elaboration for the printed version of 19 Polish Songs (Da Vinci Edition DV 21655).

In regard to the guitar part, we tried to keep as much as possible to the original tones, in order to stay very close to the Chopin’s way of writing. At the same time we essayed to enhance the sonic and expressive features of the guitar and its accompaniment quality by replacing, where necessary, the very pianistic passages with the first XIX century guitar ones. We also aimed to find an homogeneous range within which a medium voice could move easily. In a 1978 article, the musicologist Thomas F. Heck was encouraging the guitarists to face better than Diabelli the Schubert’s Lieder transcriptions. He affirmed: “Schubert’s Lieder for guitar… it’s possible!”.

Year 2020 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads