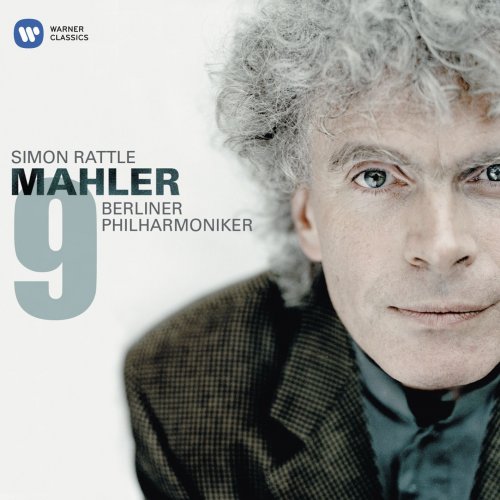

Simon Rattle, Berliner Philharmoniker - Mahler: Symphony No. 9 (2008) Hi-Res

BAND/ARTIST: Simon Rattle, Berliner Philharmoniker

- Title: Mahler: Symphony No. 9

- Year Of Release: 2008

- Label: Warner Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC 24bit-44.1kHz / FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:23:31

- Total Size: 868 Mb / 406 Mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

1. Symphony No. 9: I. Andante comodo 28:56

2. Symphony No. 9: II. Im Tempo eines gemächlichen Ländlers. Etwas täppisch und sehr derb 15:56

3. Symphony No. 9: III. Rondo-Burleske (Allegro assai. Sehr trotzig) 12:37

4. Symphony No. 9: IV. Adagio (Sehr langsam und noch zurückhaltend) 26:02

Performers:

Berliner Philharmoniker

Sir Simon Rattle, conductor

1. Symphony No. 9: I. Andante comodo 28:56

2. Symphony No. 9: II. Im Tempo eines gemächlichen Ländlers. Etwas täppisch und sehr derb 15:56

3. Symphony No. 9: III. Rondo-Burleske (Allegro assai. Sehr trotzig) 12:37

4. Symphony No. 9: IV. Adagio (Sehr langsam und noch zurückhaltend) 26:02

Performers:

Berliner Philharmoniker

Sir Simon Rattle, conductor

Mahler’s Ninth has been a fortunate symphony on record. From Bruno Walter "live" in Vienna in 1938, only days before the Nazis marched in, to this new recording conducted by Simon Rattle in post-cold-war Berlin in late 2007, this work has always brought out the best in conductors and orchestras when the microphones were on. It is a work that seems to challenge them to reach deep, find new ideas, new ways of referencing the life of its composer, his time, its place in musical history and the responses it can provoke in we the listeners. Perhaps it is the profundity of the work itself that taps into something profound in players and listeners and inspires them, or perhaps it is just luck all along. What ever it is, this has always been the hardest of all the Mahler symphonies of which to recommend one recording, so spoilt for choice is the buyer. When I first wrote my Mahler recordings survey for this work some years ago I ruthlessly concluded that there were five absolutely outstanding versions on record, the crème de la crème, that address the work in slightly different ways but none of which I would ever wish to be without. These were great recordings conducted by Walter (Sony SM2K 64452 his second version), Klemperer (EMI 5 67036 2), Horenstein (Vox CDX2 5509 his only studio version), Barbirolli (EMI (72435679252) and Haitink (Philips 4622992). The most recent of these was Haitink’s from the 1970s and whilst there have been other excellent recordings of the Ninth released since then (Boulez and Abbado on DG spring to mind as superb) there have been none that I would quite place among what I consider to be the five elect. Until now.

This is Simon Rattle’s second recording of the work. His first was a "live" performance with the Vienna Philharmonic recorded for broadcast by Austrian Radio which EMI then issued in 1998. I had this to say about it in my survey of Ninth recordings:

"Simon Rattle's version on EMI (5 56580 2) also records "live" a first appearance with one of the great European orchestras, in this case the Vienna Philharmonic. It shares the same thought world and general approach as the Bernstein but doesn't, I think, quite convince in its own way. Another problem I have is the wide dynamic range of the recording. In order to hear the softest sections you have to endure the loud ones at a volume setting that could loosen the slates on your roof."

Let me say straight away that this new recording addresses every aspect of the Vienna one that I found ruled it out. The wide emotional extremes that Rattle indulged in, for me unconvincingly, like someone wearing borrowed clothes, have been banished for an ideal medium of head with heart. The wide dynamic range that I found so troubling has likewise been replaced by ideal balancing all round both by the conductor and the engineers. It is not often that a conductor’s second recording of a Mahler work results in an emphatic improvement but that is triumphantly the case here. So for the duration of this review I shall not mention Rattle’s first recording again. Suffice to say that if you have it then you need to replace it now.

After reaching the end of the new recording for the first time, among the strongest feelings I had overall was how it miraculously seemed to have in it all the elements that I admired most in my five elect recordings, pointing me towards a remarkable thought that I might even be in the presence of an ideal recording of Mahler’s Ninth. Here is the clarity, the honesty, the "Brueghelesque" primary coloured toughness, the Stoicism of Klemperer, promoting the work as precursor of Modernist musical thought. But this is tempered by the definite old-world mellowness of expressive legato that recalls Walter at his most persuasive, especially where the emotional core calls for it. Then, when needed, the "dark night of the soul" that Horenstein brings throws its broad shadow across the landscape and threatens to trouble the waking hours. The extra emotional charge of Barbirolli runs through it like a rich vein of feeling too but, as with Sir John, it never threatens to overwhelm and preserves that crucial head/heart balance Barbirolli was so good at in Mahler. If this wasn’t enough, Rattle also seems to share Haitink’s ability to simply let the music speak for itself overall. A feeling that the music is playing itself, that there is minimal intervention, a superb care for score inner detail that lets you hear aspects that, even after decades, you had not noticed before. This last is an extra plus to the new Rattle recording for me. It is as if every bar has been rethought and with an orchestra that clearly knows the work intimately we the listener can experience something genuinely new that moves the work into another era. Where Haitink’s was the Mahler Ninth of the late 20th century, this new Rattle is the Mahler Ninth of the early 21st. Be very clear, however, that this apparent bar by bar rethinking does not result in the kind of strangling "micromanagement" that spoilt Rattle’s recording of Maher’s Fifth with the same orchestra. Rattle never puts a foot wrong in delivering for us a complete view of this work that satisfies at a very deep level indeed.

The opening does not emerge from the usual dreamy silence it does so often. Those fragmentary motifs are remarkably delineated here, not dreamy at all, and appear in this way as a statement of the intent of a creative clarity that will not flag until the end. The close balancing of the woodwind recalls Klemperer again and the clarity of the inner string parts in particular point to a regard for the contrapuntal texture of the work that is absorbing from the start. You find you want to listen hard for tone colours that you might not have appreciated before. Rattle also observes with rare precision the variations in tempi in the Exposition that inform the opening pages of this movement and which, observed as they are each time the material returns, has the effect of knitting together the vast movement at the level of deep structure. All flows, though. There is nowhere an episodic feel, so carefully has Rattle thought the movement out and how closely his orchestra follow him. In the Development up to the first collapse climax at 201-203 again I was taken by the clarity of the counterpoint but also by the sense of forward momentum at what is a near-perfect Andante comodo. Notice the keening solo flute and also the tolling harp at the bass end, often not usually heard as well as this. The harp part is especially well served in this recording and I promise you will hear it in a way you have not heard it before. Following the first collapse climax, in the section marked Leidenschaftlich (Passionate) hear how the lower strings really dig into the music with terrific verve. The clarity of the string parts makes a Bergian feel to the music which is perfectly appropriate and it is also worth pointing out here how the lebwohl motif gets delivered with a spine-tingling sense of portent, the brass players absolutely at one. After this the way that the disparate material is gathered together from silence is masterly and the main climax at 314-318 is built to with an unerring sense of momentum so that when it comes there is a fearsome inevitability. The trombones roar out the opening rhythm but now they are in proportion to the rest, part of the texture rather than detached from it. At 319-346 Rattle catches absolutely the marking Wie ein schwerer Kondukt (Like a solemn funeral procession) just as Barbirolli did with the same orchestra back in 1963. In the Recapitulation the episode of the flute and horn solo is another passage that seems to have been thought through again so as to sound new and strange. It is certainly played superbly by the Berlin players. In this final part of the long movement the impression of the lyrical and the ugly being held together in the same music is very strong. This may be the music of long remembrance but it is a muscular lyricism, the memories of a man of the world, and so the whole first movement is summed up in this way. The heart and the head and held in perfect balance from first bar to last, lyrical and ugly, old world and new world, reality and dream.

Rattle correctly sees the two central movements as the ugly side of life, the most vicious music Mahler ever wrote, is how he described them in a recent interview. The second movement is everything you hate about the countryside, the third is everything you hate about the city, he tells us. I wouldn‘t wildly disagree with that as an interpretation, even though Mahler himself might baulk at such programmatic thoughts. In the second movement the separate dance episodes are well marked out for us by a careful attention to the three different tempi. In the opening landler I liked especially the really ethnic digging in of the strings as they swing into the main material Too often this is allowed to pass by the conductor with hardly a nod. The waltz material has a backward glancing lilt but does not dilute the feeling that right through Mahler is dancing to death before us. The response of the orchestra is absolutely faultless with whip-crack precision and ensemble but never sacrificing soul, the feeling of a story being told and the sound of woodwind against strings in perfect balance is a special joy. The Berliners are also remarkably unbuttoned at times. "How potent cheap music is," as Noel Coward once observed. Again, compliments to the engineers too here, but also to Rattle for the excellent balancing. The same applies to the Rondo-Burleske third movement. This is Mahler going to the limit of expression and is a logical development from the second movement and so it sounds here. Under Rattle it is a controlled environment to begin with, all kinetic energy in a slightly held-back tempo, but the significance of this does not become clear until the end. In the wonderful lyrical interlude Rattle makes the crucial tempo choice with ease - neither too slow that if seems detached from the rest, nor too fast that we miss its lyrical power. And just listen to the nostalgia in the high trumpet solos. When the Rondo Burleske does return, Rattle conducts it like Horenstein does in his "live" recordings. Gradually screwing up the tempo as the coda approaches so that, when the end comes, by then the whole movement is going to hell like a juggernaut out of control, justifying the controlled tempo in the first part.

For Mahler’s stoic elegy on life and approaching death in the fourth movement Simon Rattle adopts an appropriately stoic demeanour. Not for him a mawkish, drawn out, emotionally over-heated outpouring that satisfies on just a surface level. In keeping with the rest of the work’s emotional mapping, he gives a reading that balances the great depth of feeling written into the music with a sharpness of focus that burns into the mind in its own terms. The strings at the very start are powerful and questing. They draw the melodies with a confident tone of voice and a timbre that again recalls Klemperer. Whilst Rattle conveys the power of the emotions present, by his unwillingness to indulge them with overt emphasis he keeps an intellectual frame which gives point to the emotion and makes for a more human response. So the man of the world we met at the end of the first movement reflecting on times past now reflects on mortality as he had pretty well for all of his life but now in the knowledge that his own end may be closer. Mahler was not at this point in his life, as you still wrongly hear, terminally ill. He was still firing on all cylinders where life and career was concerned. But he was more than ever aware of his own mortality at this point and able descant on it, carry on the theses he had explored previously in "Das Lied Von Der Erde." In the central section of the movement the intimate details are woven here into a timeless tapestry with a degree of chamber-like playing by the orchestra that is breathtaking. Here are players who are really listening to each other. The main climax, where the high violins rear up and then usher in a full-throated noble assertion of the primacy of life, emerges naturally from the rest and is delivered with a wonderful, full but firm tone that prepares for the long, soft coda. The long close of the work itself has seldom been played so well as it is here. The many silences are perfectly observed, the fragments of themes delivered with breathtaking quiet, but they are never allowed to merge into those silences and become comatose which they can sometimes do. It is a careful judgement but one that Rattle succeeds in. I was reminded that here was a conductor of Mahler’s Ninth who knows Vaughan Williams’s Sixth with its own very particular soft and fragmentary close. Vaughan Williams quoted Shakespeare’s "The Tempest" at the same point in his symphony and that quote appears absolutely appropriate in Rattle’s closing of Mahler’s Ninth: "We are such stuff as dreams are made on and our little life is rounded with a sleep."

So much depends on how you believe this work should be played and interpreted. I am certain there will be many Mahlerites who will find what I call Rattle’s excellent "head and heart balance" here leaves them short. People who want the Ninth to be an excuse to climb on to the couch and pour out the angst by the shovel need to go to conductors like Bernstein, Tennstedt or Levine for that. But I believe conversely that it is in fact recordings like that which leave us short. This work is far deeper and more rounded than those which just operate on a high-octane emotional level and leave no room for the kind of Stoicism shot through with intellectual rigour of a Rattle or Klemperer. Returning to the recordings I listed at the start of this review as being, for me, the outstanding ones I would not say this new recording supplants any of them. However, I am convinced that it joins them as one of the finest recordings of the work that I have ever heard in terms of conception, playing and recording .

If someone who was contemplating buying a Mahler Ninth for the very first time were to ask my opinion I would reply without hesitation that this is the one to have. As a first recording it is near ideal in delivering Mahler‘s Mahler Ninth as opposed to that of the conductor on the rostrum and it deserves the highest possible recommendation. -- Tony Duggan

This is Simon Rattle’s second recording of the work. His first was a "live" performance with the Vienna Philharmonic recorded for broadcast by Austrian Radio which EMI then issued in 1998. I had this to say about it in my survey of Ninth recordings:

"Simon Rattle's version on EMI (5 56580 2) also records "live" a first appearance with one of the great European orchestras, in this case the Vienna Philharmonic. It shares the same thought world and general approach as the Bernstein but doesn't, I think, quite convince in its own way. Another problem I have is the wide dynamic range of the recording. In order to hear the softest sections you have to endure the loud ones at a volume setting that could loosen the slates on your roof."

Let me say straight away that this new recording addresses every aspect of the Vienna one that I found ruled it out. The wide emotional extremes that Rattle indulged in, for me unconvincingly, like someone wearing borrowed clothes, have been banished for an ideal medium of head with heart. The wide dynamic range that I found so troubling has likewise been replaced by ideal balancing all round both by the conductor and the engineers. It is not often that a conductor’s second recording of a Mahler work results in an emphatic improvement but that is triumphantly the case here. So for the duration of this review I shall not mention Rattle’s first recording again. Suffice to say that if you have it then you need to replace it now.

After reaching the end of the new recording for the first time, among the strongest feelings I had overall was how it miraculously seemed to have in it all the elements that I admired most in my five elect recordings, pointing me towards a remarkable thought that I might even be in the presence of an ideal recording of Mahler’s Ninth. Here is the clarity, the honesty, the "Brueghelesque" primary coloured toughness, the Stoicism of Klemperer, promoting the work as precursor of Modernist musical thought. But this is tempered by the definite old-world mellowness of expressive legato that recalls Walter at his most persuasive, especially where the emotional core calls for it. Then, when needed, the "dark night of the soul" that Horenstein brings throws its broad shadow across the landscape and threatens to trouble the waking hours. The extra emotional charge of Barbirolli runs through it like a rich vein of feeling too but, as with Sir John, it never threatens to overwhelm and preserves that crucial head/heart balance Barbirolli was so good at in Mahler. If this wasn’t enough, Rattle also seems to share Haitink’s ability to simply let the music speak for itself overall. A feeling that the music is playing itself, that there is minimal intervention, a superb care for score inner detail that lets you hear aspects that, even after decades, you had not noticed before. This last is an extra plus to the new Rattle recording for me. It is as if every bar has been rethought and with an orchestra that clearly knows the work intimately we the listener can experience something genuinely new that moves the work into another era. Where Haitink’s was the Mahler Ninth of the late 20th century, this new Rattle is the Mahler Ninth of the early 21st. Be very clear, however, that this apparent bar by bar rethinking does not result in the kind of strangling "micromanagement" that spoilt Rattle’s recording of Maher’s Fifth with the same orchestra. Rattle never puts a foot wrong in delivering for us a complete view of this work that satisfies at a very deep level indeed.

The opening does not emerge from the usual dreamy silence it does so often. Those fragmentary motifs are remarkably delineated here, not dreamy at all, and appear in this way as a statement of the intent of a creative clarity that will not flag until the end. The close balancing of the woodwind recalls Klemperer again and the clarity of the inner string parts in particular point to a regard for the contrapuntal texture of the work that is absorbing from the start. You find you want to listen hard for tone colours that you might not have appreciated before. Rattle also observes with rare precision the variations in tempi in the Exposition that inform the opening pages of this movement and which, observed as they are each time the material returns, has the effect of knitting together the vast movement at the level of deep structure. All flows, though. There is nowhere an episodic feel, so carefully has Rattle thought the movement out and how closely his orchestra follow him. In the Development up to the first collapse climax at 201-203 again I was taken by the clarity of the counterpoint but also by the sense of forward momentum at what is a near-perfect Andante comodo. Notice the keening solo flute and also the tolling harp at the bass end, often not usually heard as well as this. The harp part is especially well served in this recording and I promise you will hear it in a way you have not heard it before. Following the first collapse climax, in the section marked Leidenschaftlich (Passionate) hear how the lower strings really dig into the music with terrific verve. The clarity of the string parts makes a Bergian feel to the music which is perfectly appropriate and it is also worth pointing out here how the lebwohl motif gets delivered with a spine-tingling sense of portent, the brass players absolutely at one. After this the way that the disparate material is gathered together from silence is masterly and the main climax at 314-318 is built to with an unerring sense of momentum so that when it comes there is a fearsome inevitability. The trombones roar out the opening rhythm but now they are in proportion to the rest, part of the texture rather than detached from it. At 319-346 Rattle catches absolutely the marking Wie ein schwerer Kondukt (Like a solemn funeral procession) just as Barbirolli did with the same orchestra back in 1963. In the Recapitulation the episode of the flute and horn solo is another passage that seems to have been thought through again so as to sound new and strange. It is certainly played superbly by the Berlin players. In this final part of the long movement the impression of the lyrical and the ugly being held together in the same music is very strong. This may be the music of long remembrance but it is a muscular lyricism, the memories of a man of the world, and so the whole first movement is summed up in this way. The heart and the head and held in perfect balance from first bar to last, lyrical and ugly, old world and new world, reality and dream.

Rattle correctly sees the two central movements as the ugly side of life, the most vicious music Mahler ever wrote, is how he described them in a recent interview. The second movement is everything you hate about the countryside, the third is everything you hate about the city, he tells us. I wouldn‘t wildly disagree with that as an interpretation, even though Mahler himself might baulk at such programmatic thoughts. In the second movement the separate dance episodes are well marked out for us by a careful attention to the three different tempi. In the opening landler I liked especially the really ethnic digging in of the strings as they swing into the main material Too often this is allowed to pass by the conductor with hardly a nod. The waltz material has a backward glancing lilt but does not dilute the feeling that right through Mahler is dancing to death before us. The response of the orchestra is absolutely faultless with whip-crack precision and ensemble but never sacrificing soul, the feeling of a story being told and the sound of woodwind against strings in perfect balance is a special joy. The Berliners are also remarkably unbuttoned at times. "How potent cheap music is," as Noel Coward once observed. Again, compliments to the engineers too here, but also to Rattle for the excellent balancing. The same applies to the Rondo-Burleske third movement. This is Mahler going to the limit of expression and is a logical development from the second movement and so it sounds here. Under Rattle it is a controlled environment to begin with, all kinetic energy in a slightly held-back tempo, but the significance of this does not become clear until the end. In the wonderful lyrical interlude Rattle makes the crucial tempo choice with ease - neither too slow that if seems detached from the rest, nor too fast that we miss its lyrical power. And just listen to the nostalgia in the high trumpet solos. When the Rondo Burleske does return, Rattle conducts it like Horenstein does in his "live" recordings. Gradually screwing up the tempo as the coda approaches so that, when the end comes, by then the whole movement is going to hell like a juggernaut out of control, justifying the controlled tempo in the first part.

For Mahler’s stoic elegy on life and approaching death in the fourth movement Simon Rattle adopts an appropriately stoic demeanour. Not for him a mawkish, drawn out, emotionally over-heated outpouring that satisfies on just a surface level. In keeping with the rest of the work’s emotional mapping, he gives a reading that balances the great depth of feeling written into the music with a sharpness of focus that burns into the mind in its own terms. The strings at the very start are powerful and questing. They draw the melodies with a confident tone of voice and a timbre that again recalls Klemperer. Whilst Rattle conveys the power of the emotions present, by his unwillingness to indulge them with overt emphasis he keeps an intellectual frame which gives point to the emotion and makes for a more human response. So the man of the world we met at the end of the first movement reflecting on times past now reflects on mortality as he had pretty well for all of his life but now in the knowledge that his own end may be closer. Mahler was not at this point in his life, as you still wrongly hear, terminally ill. He was still firing on all cylinders where life and career was concerned. But he was more than ever aware of his own mortality at this point and able descant on it, carry on the theses he had explored previously in "Das Lied Von Der Erde." In the central section of the movement the intimate details are woven here into a timeless tapestry with a degree of chamber-like playing by the orchestra that is breathtaking. Here are players who are really listening to each other. The main climax, where the high violins rear up and then usher in a full-throated noble assertion of the primacy of life, emerges naturally from the rest and is delivered with a wonderful, full but firm tone that prepares for the long, soft coda. The long close of the work itself has seldom been played so well as it is here. The many silences are perfectly observed, the fragments of themes delivered with breathtaking quiet, but they are never allowed to merge into those silences and become comatose which they can sometimes do. It is a careful judgement but one that Rattle succeeds in. I was reminded that here was a conductor of Mahler’s Ninth who knows Vaughan Williams’s Sixth with its own very particular soft and fragmentary close. Vaughan Williams quoted Shakespeare’s "The Tempest" at the same point in his symphony and that quote appears absolutely appropriate in Rattle’s closing of Mahler’s Ninth: "We are such stuff as dreams are made on and our little life is rounded with a sleep."

So much depends on how you believe this work should be played and interpreted. I am certain there will be many Mahlerites who will find what I call Rattle’s excellent "head and heart balance" here leaves them short. People who want the Ninth to be an excuse to climb on to the couch and pour out the angst by the shovel need to go to conductors like Bernstein, Tennstedt or Levine for that. But I believe conversely that it is in fact recordings like that which leave us short. This work is far deeper and more rounded than those which just operate on a high-octane emotional level and leave no room for the kind of Stoicism shot through with intellectual rigour of a Rattle or Klemperer. Returning to the recordings I listed at the start of this review as being, for me, the outstanding ones I would not say this new recording supplants any of them. However, I am convinced that it joins them as one of the finest recordings of the work that I have ever heard in terms of conception, playing and recording .

If someone who was contemplating buying a Mahler Ninth for the very first time were to ask my opinion I would reply without hesitation that this is the one to have. As a first recording it is near ideal in delivering Mahler‘s Mahler Ninth as opposed to that of the conductor on the rostrum and it deserves the highest possible recommendation. -- Tony Duggan

Classical | FLAC / APE | HD & Vinyl

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads