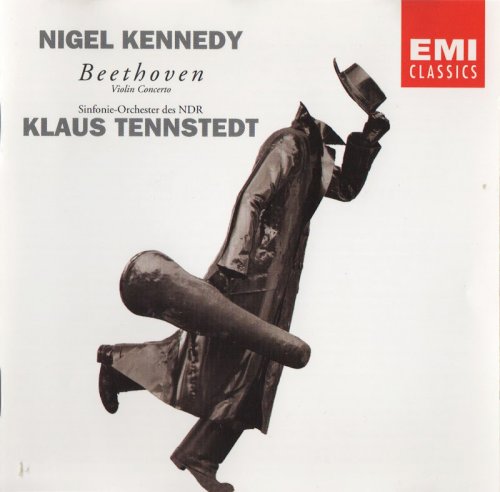

Nigel Kennedy, Klaus Tennstedt - Beethoven: Violin Concerto, J.S. Bach: Partita No. 3, Sonata No. 3 (1992)

BAND/ARTIST: Nigel Kennedy, Klaus Tennstedt

- Title: Beethoven: Violin Concerto, J.S. Bach: Partita No. 3, Sonata No. 3

- Year Of Release: 1992

- Label: EMI Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

- Total Time: 59:19

- Total Size: 273 Mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

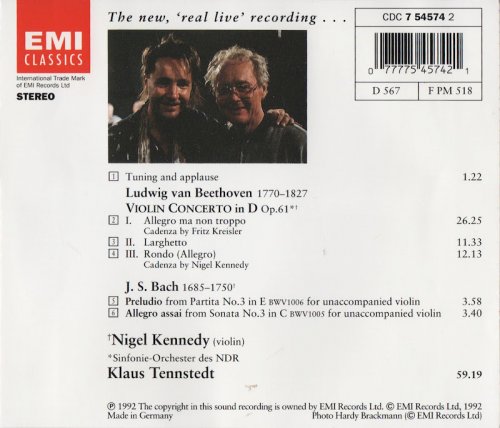

Tracklist:

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

01. Tuning and applause [0:01:23.12]

02. Violin Concerto in D Op.61 - I. Allegro ma non troppo [0:26:25.55]

03. Violin Concerto in D Op.61 - II. Larghetto [0:11:32.73]

04. Violin Concerto in D Op.61 - III. Rondo (Allegro) [0:12:15.32]

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

05. Preludio from Partita No.3 in E [0:04:01.48]

06. Allegro assai from Sonata No.3 in C [0:03:40.37]

Performers:

Nigel Kennedy - violin

Sinfonie-Orchester des NDR

Klaus Tennstedt - conductor

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

01. Tuning and applause [0:01:23.12]

02. Violin Concerto in D Op.61 - I. Allegro ma non troppo [0:26:25.55]

03. Violin Concerto in D Op.61 - II. Larghetto [0:11:32.73]

04. Violin Concerto in D Op.61 - III. Rondo (Allegro) [0:12:15.32]

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

05. Preludio from Partita No.3 in E [0:04:01.48]

06. Allegro assai from Sonata No.3 in C [0:03:40.37]

Performers:

Nigel Kennedy - violin

Sinfonie-Orchester des NDR

Klaus Tennstedt - conductor

For the third time in a row EMI offers the Beethoven Violin Concerto with one of its star violinists recorded live. This first recording of the Beethoven by Nigel Kennedy follows the pattern of the Perlman and Chung versions 1 have listed, but with a difference. Undeniably in each instance the personal magnetism of the star performer comes over with extra intensity, and Nigel Kennedy is this time most understandingly supported, as Chung was too, by Klaus Tennstedt. The overall timing of 59 minutes for the concerto and two brief solo Bach encores will alert the keen collector to the slowness of the Beethoven reading, but that figure is greatly augmented by many minutes of applause and tuning up. Just why EMI should think that collectors should want to hear so many of the scrag-end sounds of a concert repeatedly. However, these are tracked separately and so can be excluded if you wish.

Allowing for irritation over that, the Beethoven performance is most compelling. In direct comparison with Perlman and Chung, Kennedy is freer with his expressive rubato. If Chung proved a more volatile Beethovenian than Perlman, Kennedy goes one step further, and Tennstedt is masterly in matching his soloist, having no doubt learnt something from recording the Brahms concerto with Kennedy in a comparably slow reading. Though at 26 minutes the overall timing for the first movement is substantially slower than Perlman and Chung (neither of them fast readings), the impression is rarely if ever of dawdling but of flexibility. Certainly a live occasion helps to make such a flexible approach sound more natural and persuasive than it did in the studio recording of the Brahms. Nor is it just a question of rallentando expressiveness, for Kennedy will equally press ahead in eagerness. Repeatedly one is caught by the magic of a phrase as one has never heard it before. With such rapt playing that magnetism in its way is sufficient justification, even if for repeated listening a firmer sense of structure is likely to prove more enduringly satisfying.

Kennedy plays the Kreisler cadenza in a comparably volatile way, but then the lovely lead-in to the coda brings the music almost to a halt, with the coda following at what at first seems an impossibly slow speed. Yet the inner depth of the performance at the most hushed pianissimo could hardly be more intense, and similarly in the central Larghetto Kennedy and Tennstedt sustain an almost unbelievably slow tempo through their rapt dedication. So the lovely third theme, when it first appears, is as poignant in its lyrical simplicity as l have ever known it, becoming fuller and warmer at its second appearance, decorated, magical both times.

The finale is taken at an easy lilt, allowing the dotted rhythms in compound time to sound ideally springy. After the central episode Kennedy adopts an exaggerated pianissimo in the repeat of the main theme, but again it makes the ears prick up. The oddity is his own cadenza in that last movement, which starts conventionally enough with copious double-stopping, then brings a hint of the main theme of the first movement before indulging in a curious atonal passage with quarter-tones. Glenn Gould, one remembers, had his atonal cadenza for the Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 1, and it struck me that Kennedy might be aiming to become the Glenn Gould of the violin. There are worse fates. The Bach encores are lively and expressive but next to the concerto unremarkable. The recording of the violin is excellent, though orchestral textures in tuttis tend to sound a little muddy. -- Edward Greenfield

Allowing for irritation over that, the Beethoven performance is most compelling. In direct comparison with Perlman and Chung, Kennedy is freer with his expressive rubato. If Chung proved a more volatile Beethovenian than Perlman, Kennedy goes one step further, and Tennstedt is masterly in matching his soloist, having no doubt learnt something from recording the Brahms concerto with Kennedy in a comparably slow reading. Though at 26 minutes the overall timing for the first movement is substantially slower than Perlman and Chung (neither of them fast readings), the impression is rarely if ever of dawdling but of flexibility. Certainly a live occasion helps to make such a flexible approach sound more natural and persuasive than it did in the studio recording of the Brahms. Nor is it just a question of rallentando expressiveness, for Kennedy will equally press ahead in eagerness. Repeatedly one is caught by the magic of a phrase as one has never heard it before. With such rapt playing that magnetism in its way is sufficient justification, even if for repeated listening a firmer sense of structure is likely to prove more enduringly satisfying.

Kennedy plays the Kreisler cadenza in a comparably volatile way, but then the lovely lead-in to the coda brings the music almost to a halt, with the coda following at what at first seems an impossibly slow speed. Yet the inner depth of the performance at the most hushed pianissimo could hardly be more intense, and similarly in the central Larghetto Kennedy and Tennstedt sustain an almost unbelievably slow tempo through their rapt dedication. So the lovely third theme, when it first appears, is as poignant in its lyrical simplicity as l have ever known it, becoming fuller and warmer at its second appearance, decorated, magical both times.

The finale is taken at an easy lilt, allowing the dotted rhythms in compound time to sound ideally springy. After the central episode Kennedy adopts an exaggerated pianissimo in the repeat of the main theme, but again it makes the ears prick up. The oddity is his own cadenza in that last movement, which starts conventionally enough with copious double-stopping, then brings a hint of the main theme of the first movement before indulging in a curious atonal passage with quarter-tones. Glenn Gould, one remembers, had his atonal cadenza for the Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 1, and it struck me that Kennedy might be aiming to become the Glenn Gould of the violin. There are worse fates. The Bach encores are lively and expressive but next to the concerto unremarkable. The recording of the violin is excellent, though orchestral textures in tuttis tend to sound a little muddy. -- Edward Greenfield

Classical | FLAC / APE | CD-Rip

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads