Western Classical music has established an increasingly pronounced hiatus between “composition”, “performance” and “improvisation”. On the one hand, there is the “creator” of music, who writes down a score with instructions for performance; on the other, there is the player who realizes these instructions and actualizes the music. Improvisers share some features with composers and some with performers: they play their own music, but, generally speaking, this music is not written down beforehand, at least not with all details. However, this misleadingly simple scheme is highly deceptive. No composer, actually, writes down all details of a piece; no performer simply executes the instructions without a creative component; no improviser starts from scratch with no pre-established structure or reference. Thus, even in today’s very organized musical world, the boundaries between these three distinct figures are not as neat as one might imagine. Still, they are much clearer today than they were even in the recent past. For centuries, musicians in many “cultivated” and “popular” traditions around the world have intended the transmitted “music” (be it a tune, a harmonic or rhythmic scheme, or even a composed piece) as a creative stimulus rather than as a set of instructions. It was not just admissible, but rather necessary to intervene on that heritage with a carefully balanced mix of respect and innovation. A performer who simply played “the notes” received from tradition could be dismissed as unimaginative and arid; one who went too far from the established model could produce a music felt as unintelligible and nonsensical by his or her contemporaries.

Fantasy was prized as an appreciated value by listeners, as happens today with jazz improvisation and in many non-classical traditions. Not only it demonstrated the performer’s creative artistry; it also showed his or her technical accomplishment and knowledge of the structures of the musical language. Only those who master the finest nuances of a language can venture to create extemporaneous poetry in that language, and the same applies to music. Only those who are perfectly skilled in all of the trade secrets of instrumental technique, of harmony and counterpoint, may be really free to improvise without risking catastrophes.

Both performers and listeners, however, will feel on safer ground if there is a clear and known starting point, which may be – as said before – a known tune or harmonic scheme. For ages, the art of “diminution” grounded itself precisely on this principle: the notes of a tune were understood as markers of a musical space, and the space delimited by them could be “filled” in a variety of ways according to the performer/improviser’s skill and taste. This is the principle behind the Theme and Variations, but also behind many Fantasies and similar works.

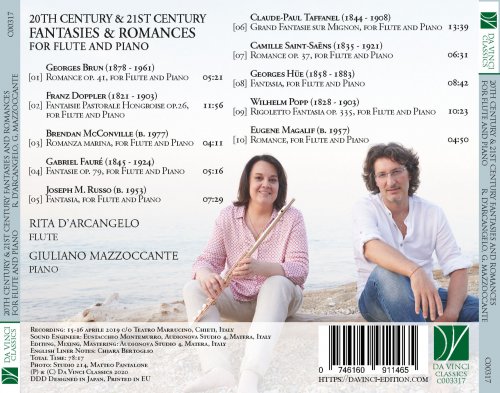

This Da Vinci Classics album leads the listeners in the discovery of a largely unknown repertoire, and, particularly, of a style of making music which may seem to have disappeared from today’s “classical” music world, but – as will be seen and heard – is instead very much alive. The twentieth century mainstream classical music school saw an increasing tendency by the composers to over-determine their works; performers were gradually relegated to a role of mere executants of scores which left very little to their own creativity and freedom. By way of contrast, numerous composers in that century – and also today – cultivated a more old-fashioned “alliance” between creator and performer. Instead of seeing the player as an enemy which had to be subjugated, they wrote pieces in which performers could display all of their musical and technical skills, but also their own fantasy and inspiration.

The flute repertoire could boast many such pieces dating mostly from the nineteenth century (even though, by its very nature, improvisation and ornamentation on the flute were two of the first and more lasting experiences of human musicianship). Frequently, the skeleton of these Fantasies was constituted by operatic themes, or other tunes often coming from the vocal repertoire. In this case, too, the reason is easily understood: both the flute and the human voice depend on breathing, and the flute can be seen as a “hyper voice” which may achieve levels of virtuosity unattainable by singers, and which therefore impress the listeners as “super human” results which however maintain a markedly “human” component. A typical example of this repertoire is Wilhelm Popp’s Rigoletto Fantasie. Popp, a composer who was also an appreciated flutist in the second half of the nineteenth century, was one of the first to select some of the best-known tunes from Verdi’s Rigoletto and to rework them in a brilliant pastiche weaving melodies in a web of virtuosity and expressivity. The success of this Fantasie was so impressive that Popp would continue drawing from Verdi’s operas also in the following years, confirming his standing as one of the masters of the flute repertoire. A similar attitude can be observed in the Fantaisie pastorale hongroise op. 26 by Franz Doppler, another famous flute player who was Popp’s contemporary. Doppler knew Hungarian music deeply, also due to his cooperation with the Budapest Opera for which he wrote many acclaimed works; moreover, thanks to his friendship with his former mentor Franz Liszt, he had orchestrated Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies. As happens with Liszt’s models, Doppler’s Fantaisie gracefully and imaginatively connects folk tunes (or tunes with a folk-like flavour), frequently employing them as pretexts for the most dazzling virtuosity.

No less complex to play is the Fantaisie op. 79 by Gabriel Fauré, who wrote it in 1898 upon a commission by legendary flutist Paul Taffanel , a leading performer at the Opéra and the driving force behind the Orchestre de la Société des Instruments à Vent. At that time, Taffanel was the Professor of flute at the Paris Conservatoire, where Fauré taught composition; that institution used to commission the final examination pieces to some of the greatest musicians of the era. This laudable habit has given us numerous among the finest examples of French music, particularly in the case of instruments with little solo tradition (of course, this cannot be said of the flute). Fauré’s Fantaisie was created as the Pièce de concours for the summer exams, and the composer took the task very seriously, to the point of relinquishing some of his earlier commitments. Writing to a student, Fauré stated: “I am drowned in the Taffanel and plunged up to my neck in scales, arpeggios, and staccati! I have already perpetrated 104 bars of this irksome torture”. As happens with many similar works, a slow and cantabile introduction is in fact followed by pyrotechnical technical passages; Fauré’s talent, however, never allows this dazzling virtuosity to decay into a mere display of difficulties. Not entirely sure of where the boundary was between very difficult and unplayable on the flute, Fauré asked Taffanel, the piece’s dedicatee, to modify the impossible passages; since the manuscript does not survive, we do not know how pronounced were Taffanel’s interventions. Certainly, however, they were approved by Fauré, and were enacted by someone who was a fine composer in his own right, as is demonstrated by Taffanel’s Mignon Fantasy also recorded here. The tunes on which this famous piece is based are excerpted from a very successful opera by Ambroise Thomas, and Taffanel managed not only to employ them in a consistent and well-knit fashion, but rather to evoke the opera’s overall atmospheres, style and colours in a work whose expressive dimension is not inferior to its technical aspects. Taffanel was the dedicatee also of Saint-Saëns’ Romance op. 37, which, like many other works sharing the same title, is more inclined to the lyrical aspect than to that of glittering virtuosity. A similarly singing and narrative style suffuses the Romance op. 41 by Georges Brun, dedicated to another great French flautist, Georges Barrère. It is a short but touching piece, which requires warmth of tone and an extended dynamic range. The same expressive qualities are necessary in the initial section of yet another Fantaisie, the one written by Georges Hüe. In this case, however, as in those of other Fantasies discussed above, the piece soon leaves this enchanted atmosphere, and, after a Modéré with an intense musicality, acquires decidedly virtuoso features.

Similar qualities are found also in the examples of these genres composed by contemporary musicians. This is the case, for example, with Eugene Magalif’s Romance, based on a song written by the same composer, and reworked as a flute piece for Rita D’Arcangelo. The composer’s familiarity with the world of the flute is revealed by the skill and ability with which the expressive features of the instrument are used. The same flutist also premiered the Fantasy for Flute and Piano by Joseph M. Russo, an American composer and double-bass player. In spite of the use of modern musical languages, this piece reveals its rootedness in the earlier tradition outlined throughout this musical itinerary. Analogously, and notwithstanding the obvious differences in style and personality, the Romanza marina by Brendan McConville evidently aims at a powerful narrative and evocative impact, and clearly achieves it. McConville is also an appreciated theorist of music, and the structural thought behind this seemingly effortless piece is an added value.

Over nearly two centuries, therefore, and notwithstanding innovations in the musical language and in flute technique, similar ends are pursued through different means, but a substantial continuity can be clearly observed. An album such as this can therefore lead us to appreciate how music can flexibly take new forms while maintaining similar poetic ideals.

Liner Notes by Chiara Bertoglio