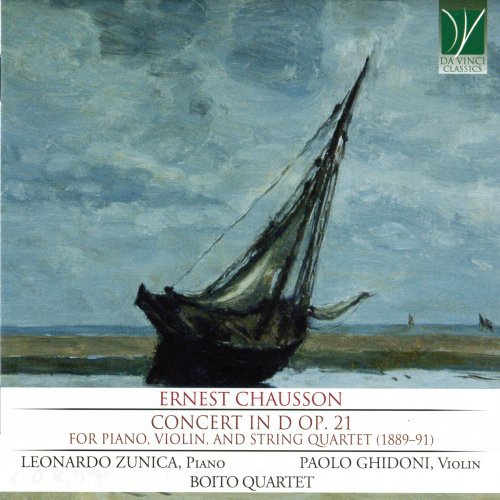

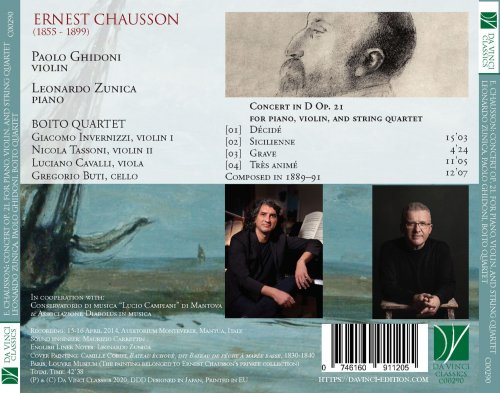

Boito Quartet, Leonardo Zunica, Paolo Ghidoni - Ernest Chausson: Concert in D Major Op. 21 (2020)

BAND/ARTIST: Boito Quartet, Leonardo Zunica, Paolo Ghidoni

- Title: Ernest Chausson: Concert in D Major Op. 21

- Year Of Release: 2020

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless

- Total Time: 00:42:40

- Total Size: 213 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Concert pour piano, violon et quatuor à cordes in D Major, Op. 21: I. Décidé

02. Concert pour piano, violon et quatuor à cordes in D Major, Op. 21: II. Sicilienne

03. Concert pour piano, violon et quatuor à cordes in D Major, Op. 21: III. Grave

04. Concert pour piano, violon et quatuor à cordes in D Major, Op. 21: IV. Très animé

Ernest Chausson (Paris, 1855 – Limay, 1899) has now abandoned, for good, the ranks of those lesser known secondary composers who, due to circumstances of reception, of fortune or to the audiences’ capricious taste, sometimes resurface from the pages of the history of music.

Being fully aware of these facts, Chausson himself cared obsessively for his position as a composer. Step by step, and with implacable rigor, the French composer examined the authenticity and value of his works; during his entire life, he had deep doubts about his professional stature, fearing the stigma of amateurishness, ruthlessly described, in those same years, by Gustave Flaubert in his unfinished novel Bouvard et Pécuchet.

Born to a wealthy and cultivated family, and precociously sensitive to every form of art (we may recall that the composer owned a very rich collection of works by French and Japanese painters), Chausson came to music relatively late, thus leaving only a few dozens of opus numbers in his catalogue. His Concerto for violin, piano and string quartet op. 21 should be numbered among the greatest masterpieces of the late-nineteenth century chamber music, among the monuments of a musical language which would shortly be shattered by the novelties introduced by composers of the new generations, such as Satie, Ravel and Debussy.

The Concert, which is to be considered neither as a Sextet nor as a properly soloistic work, given its marked concertante features, had a very tortured genesis, and absorbed the composer for almost three years. Its first drafts were presented by Chausson to his teacher, César Franck, in 1889 (the great composer would die in 1890); their correspondence allows us to acquire a precise idea of the difficulties he experienced in the process of finishing his work. In November 1890, in a letter to his friend Henry Lerolle (a painter and collector, who was the patron of Degas, Monet and Renoir, a friend to many composer and the author of a painting in which Chausson himself is portrayed), Chausson complained that the Concerto “was not progressing at all” (“ne marche pas du tout”). The following month, he was annoyed by the pressure his friend Vincent d’Indy was making on him. D’Indy, a composer who shared with Chausson the management of the Société Nationale de Musique, encouraged him to send part of the manuscript to the great Belgian violinist Eugène Ysaÿe, to whom the Concert would later be dedicated. In the same year, at Ayzac, during one of his frequent holidays, Chausson performed the Sicilienne (second movement) for Henry Duparc (today counted among the greatest French composers of Mélodies); Duparc was enthused.

However, in June 1891, Chausson wrote once more to Lerolle, asking him to wish “une bonne fin de Concert”, since the matter was leading him to “lose his head”. “One must wait with patience”, he confessed in another letter, “stop despairing and just work. Work: but it is manual work what I would need. Spinoza made eyeglasses; Tolstoy imagined himself as a shoemaker. Music does not give peace to me; rather, it is quite the opposite”.

In the autumn of 1891, the composer undertook his second, long Italian journey; he was going to stay prevailingly in Rome, where he would listen to live performances of Palestrina’s music and was enthralled, once more, by the Sistine Chapel, by Michelangelo’s Moses, by the Roman Forum. In 1892, Chausson’s life had a positive turn, both creatively and psychologically, partly thanks to the great success of the performance of the stage music for La Legènde de Sainte Cécile. In that same year, the composer finished the Concerto, whose premiere was highly acclaimed by both audience and critics. Starting from that same year, he began writing his second diary (journal intime), in which he was to write down some of his most interesting aesthetical reflections, and in which we find detailed information about the facts surrounding the Concerto’s premiere (what concerns us most here).

On February 18th, 1892, Chausson was in Brussels, listening to the rehearsals of his work, which had eventually been accomplished, and whose debut was scheduled to take place on February 26th. The extreme difficulty of the piano part had terrified young Paul Litta who, just three weeks before the premiere, gave back the manuscript. D’Indy, aware of the consequences which such a surrender could cause on Chausson’s fragile morale, asked Louis Diémer, a famous professor of piano at the Conservatory of Paris, who eventually suggested Auguste Pierret, a seventeen-years old who had been awarded a Premier Prix. On February 20th, two days before the beginning of the rehearsals, Chausson confessed his interior malaise to his diary: “[I have] always to fight, and to be vanquished, so often. How far I am from what I would like to be. The whole effort of life is to create oneself”. On the 21, Ysaÿe, who at first had aired the possibility of declining the engagement in turn, accepted to perform the Concert after receiving a heartfelt letter sent by Chausson. On February 22nd, at 10 in the morning, the first rehearsal took place:

“Everything works perfectly. All [the performers] are amiable and friendly, and very talented. Ysaÿe amazes me with his understanding. And he finds the Concerto beautiful. Am glad”. “Tuesday, February 23rd; another full day of rehearsals, this time with Pierret [who would become Chausson’s student the following year]. Everybody is enthusiastic. I feel as if I were prodigiously loving everybody”. And, on the following Thursday: “Decidedly, the success increases. I clearly see that nobody expected something that good. I am very happy”. Finally, on the 26th, the premiere took place at the Groupe des XX, an avant-garde artistic club in Brussels: “One is led to think that my music is particularly suited to the Belgians. […] All seem to find the Concerto beautiful. The performance was very good, occasionally admirable, and always very artistic. I feel light and joyful, such as I had not been feeling for a long time. This benefit and encourages me”.

This enthusiasm and this newly found trust would be crucial for the final redaction of another of the great masterpieces by Chausson, Le Poème de l’Amour et de la Mer op. 19, and for the completion of the opera in three acts Le Roi Arthus op. 23, the ultimate benchmark for the composer’s ability. Chausson, however, could never see it performed: as is well known, on June 10th, 1899, he lost his life in a dreadful bicycle accident.

Decidé

The first movement of the Concert freely follows the precepts of the Sonata Form. Chausson widens the tonal interplay, shaping at will the proportions of the sections. The result is a large-scale movement, with unceasing coups de théâtre, intensifications and lyrical openings: for their cohesion, undoubtedly, they owe much to the teachings of César Franck, while, for their unmistakable immediacy, they owe much to Jules Massenet, who had been Chausson’s first piano teacher. A fragment of the first theme is suddenly introduced by the piano. This element, made of just three notes, and with an extremely affirmative character, appears as a motto, and is, in fact, the generative principle of the Concert. Some have rightfully pointed out its similarity to the opening bars of Beethoven’s last Quartet, op. 135. From this initial cell, in fact, springs an extraordinary abundance of musical narratives, whose main protagonists are the violin (to whom the real first theme is entrusted) and the piano, whose texture comes to light in the principal narrative.

Sicilienne

The second movement should originally have borne the subtitle of Île heureuse (“Island of happiness”), similar to a song by Chabrier: this perhaps helps us to get an idea of the piece. Within the work, this movement embodies a moment of pacification. The two melodic elements entrusted to the violin articulate, with a carefully constructed melancholy, the 6/8 rhythm of the Siciliano, with its pleasurable enchantment and with a clearly modal flavour. Here too, as had happened in the first movement, Chausson seems to be attracted by processes of emotional widening, which reach their apex, in the movement’s concluding section, in a moment of great intensity, where the Sextet is employed as a miniature orchestra.

Grave

It constitutes the work’s expressive core, and can be rightfully considered among the most successful Adagios in the fin-de-siècle chamber music repertoire, thanks to its intensity and architectural mastery. Grave is not just an agogic indication: rather, it immediately projects the listener into a narrative situation of extreme and tragical intensity. The piano’s anguished initial ostinato (an element to be found throughout the piece) underscores a kind of a lamentation, played by the violin. The resulting atmosphere is clothed in a cloak of inexorability: a musical pendant to the deep meditations left by Chausson in his diaries – confessions about the man, the artist, and the central role of art (and in particular of music) in his life.

Finale – Très animé

The contrasts, which succeeded each other so variedly, and the accumulation of tension which derived from those contrasts until now, seem to precipitate in the fourth movement, but towards a positive solution: as if recovering, little by little, the trust which seemed to have disappeared in the sudden darkness of the Grave. In a concentration of vitality, this movement bears witness to the debt owed by Chausson to his apprenticeship with Franck, and to the latter’s ideas about cyclical forms. All of the melodic elements which have hitherto been heard are represented here, revealing their common kinship, and creating a kind of grandiose recapitulation culminating in an equally grandiose finale: a sumptuous conclusion for a masterpiece which had been conceived at a time soon going to be swept away by a deep renewal of the musical thought.

01. Concert pour piano, violon et quatuor à cordes in D Major, Op. 21: I. Décidé

02. Concert pour piano, violon et quatuor à cordes in D Major, Op. 21: II. Sicilienne

03. Concert pour piano, violon et quatuor à cordes in D Major, Op. 21: III. Grave

04. Concert pour piano, violon et quatuor à cordes in D Major, Op. 21: IV. Très animé

Ernest Chausson (Paris, 1855 – Limay, 1899) has now abandoned, for good, the ranks of those lesser known secondary composers who, due to circumstances of reception, of fortune or to the audiences’ capricious taste, sometimes resurface from the pages of the history of music.

Being fully aware of these facts, Chausson himself cared obsessively for his position as a composer. Step by step, and with implacable rigor, the French composer examined the authenticity and value of his works; during his entire life, he had deep doubts about his professional stature, fearing the stigma of amateurishness, ruthlessly described, in those same years, by Gustave Flaubert in his unfinished novel Bouvard et Pécuchet.

Born to a wealthy and cultivated family, and precociously sensitive to every form of art (we may recall that the composer owned a very rich collection of works by French and Japanese painters), Chausson came to music relatively late, thus leaving only a few dozens of opus numbers in his catalogue. His Concerto for violin, piano and string quartet op. 21 should be numbered among the greatest masterpieces of the late-nineteenth century chamber music, among the monuments of a musical language which would shortly be shattered by the novelties introduced by composers of the new generations, such as Satie, Ravel and Debussy.

The Concert, which is to be considered neither as a Sextet nor as a properly soloistic work, given its marked concertante features, had a very tortured genesis, and absorbed the composer for almost three years. Its first drafts were presented by Chausson to his teacher, César Franck, in 1889 (the great composer would die in 1890); their correspondence allows us to acquire a precise idea of the difficulties he experienced in the process of finishing his work. In November 1890, in a letter to his friend Henry Lerolle (a painter and collector, who was the patron of Degas, Monet and Renoir, a friend to many composer and the author of a painting in which Chausson himself is portrayed), Chausson complained that the Concerto “was not progressing at all” (“ne marche pas du tout”). The following month, he was annoyed by the pressure his friend Vincent d’Indy was making on him. D’Indy, a composer who shared with Chausson the management of the Société Nationale de Musique, encouraged him to send part of the manuscript to the great Belgian violinist Eugène Ysaÿe, to whom the Concert would later be dedicated. In the same year, at Ayzac, during one of his frequent holidays, Chausson performed the Sicilienne (second movement) for Henry Duparc (today counted among the greatest French composers of Mélodies); Duparc was enthused.

However, in June 1891, Chausson wrote once more to Lerolle, asking him to wish “une bonne fin de Concert”, since the matter was leading him to “lose his head”. “One must wait with patience”, he confessed in another letter, “stop despairing and just work. Work: but it is manual work what I would need. Spinoza made eyeglasses; Tolstoy imagined himself as a shoemaker. Music does not give peace to me; rather, it is quite the opposite”.

In the autumn of 1891, the composer undertook his second, long Italian journey; he was going to stay prevailingly in Rome, where he would listen to live performances of Palestrina’s music and was enthralled, once more, by the Sistine Chapel, by Michelangelo’s Moses, by the Roman Forum. In 1892, Chausson’s life had a positive turn, both creatively and psychologically, partly thanks to the great success of the performance of the stage music for La Legènde de Sainte Cécile. In that same year, the composer finished the Concerto, whose premiere was highly acclaimed by both audience and critics. Starting from that same year, he began writing his second diary (journal intime), in which he was to write down some of his most interesting aesthetical reflections, and in which we find detailed information about the facts surrounding the Concerto’s premiere (what concerns us most here).

On February 18th, 1892, Chausson was in Brussels, listening to the rehearsals of his work, which had eventually been accomplished, and whose debut was scheduled to take place on February 26th. The extreme difficulty of the piano part had terrified young Paul Litta who, just three weeks before the premiere, gave back the manuscript. D’Indy, aware of the consequences which such a surrender could cause on Chausson’s fragile morale, asked Louis Diémer, a famous professor of piano at the Conservatory of Paris, who eventually suggested Auguste Pierret, a seventeen-years old who had been awarded a Premier Prix. On February 20th, two days before the beginning of the rehearsals, Chausson confessed his interior malaise to his diary: “[I have] always to fight, and to be vanquished, so often. How far I am from what I would like to be. The whole effort of life is to create oneself”. On the 21, Ysaÿe, who at first had aired the possibility of declining the engagement in turn, accepted to perform the Concert after receiving a heartfelt letter sent by Chausson. On February 22nd, at 10 in the morning, the first rehearsal took place:

“Everything works perfectly. All [the performers] are amiable and friendly, and very talented. Ysaÿe amazes me with his understanding. And he finds the Concerto beautiful. Am glad”. “Tuesday, February 23rd; another full day of rehearsals, this time with Pierret [who would become Chausson’s student the following year]. Everybody is enthusiastic. I feel as if I were prodigiously loving everybody”. And, on the following Thursday: “Decidedly, the success increases. I clearly see that nobody expected something that good. I am very happy”. Finally, on the 26th, the premiere took place at the Groupe des XX, an avant-garde artistic club in Brussels: “One is led to think that my music is particularly suited to the Belgians. […] All seem to find the Concerto beautiful. The performance was very good, occasionally admirable, and always very artistic. I feel light and joyful, such as I had not been feeling for a long time. This benefit and encourages me”.

This enthusiasm and this newly found trust would be crucial for the final redaction of another of the great masterpieces by Chausson, Le Poème de l’Amour et de la Mer op. 19, and for the completion of the opera in three acts Le Roi Arthus op. 23, the ultimate benchmark for the composer’s ability. Chausson, however, could never see it performed: as is well known, on June 10th, 1899, he lost his life in a dreadful bicycle accident.

Decidé

The first movement of the Concert freely follows the precepts of the Sonata Form. Chausson widens the tonal interplay, shaping at will the proportions of the sections. The result is a large-scale movement, with unceasing coups de théâtre, intensifications and lyrical openings: for their cohesion, undoubtedly, they owe much to the teachings of César Franck, while, for their unmistakable immediacy, they owe much to Jules Massenet, who had been Chausson’s first piano teacher. A fragment of the first theme is suddenly introduced by the piano. This element, made of just three notes, and with an extremely affirmative character, appears as a motto, and is, in fact, the generative principle of the Concert. Some have rightfully pointed out its similarity to the opening bars of Beethoven’s last Quartet, op. 135. From this initial cell, in fact, springs an extraordinary abundance of musical narratives, whose main protagonists are the violin (to whom the real first theme is entrusted) and the piano, whose texture comes to light in the principal narrative.

Sicilienne

The second movement should originally have borne the subtitle of Île heureuse (“Island of happiness”), similar to a song by Chabrier: this perhaps helps us to get an idea of the piece. Within the work, this movement embodies a moment of pacification. The two melodic elements entrusted to the violin articulate, with a carefully constructed melancholy, the 6/8 rhythm of the Siciliano, with its pleasurable enchantment and with a clearly modal flavour. Here too, as had happened in the first movement, Chausson seems to be attracted by processes of emotional widening, which reach their apex, in the movement’s concluding section, in a moment of great intensity, where the Sextet is employed as a miniature orchestra.

Grave

It constitutes the work’s expressive core, and can be rightfully considered among the most successful Adagios in the fin-de-siècle chamber music repertoire, thanks to its intensity and architectural mastery. Grave is not just an agogic indication: rather, it immediately projects the listener into a narrative situation of extreme and tragical intensity. The piano’s anguished initial ostinato (an element to be found throughout the piece) underscores a kind of a lamentation, played by the violin. The resulting atmosphere is clothed in a cloak of inexorability: a musical pendant to the deep meditations left by Chausson in his diaries – confessions about the man, the artist, and the central role of art (and in particular of music) in his life.

Finale – Très animé

The contrasts, which succeeded each other so variedly, and the accumulation of tension which derived from those contrasts until now, seem to precipitate in the fourth movement, but towards a positive solution: as if recovering, little by little, the trust which seemed to have disappeared in the sudden darkness of the Grave. In a concentration of vitality, this movement bears witness to the debt owed by Chausson to his apprenticeship with Franck, and to the latter’s ideas about cyclical forms. All of the melodic elements which have hitherto been heard are represented here, revealing their common kinship, and creating a kind of grandiose recapitulation culminating in an equally grandiose finale: a sumptuous conclusion for a masterpiece which had been conceived at a time soon going to be swept away by a deep renewal of the musical thought.

Year 2020 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads