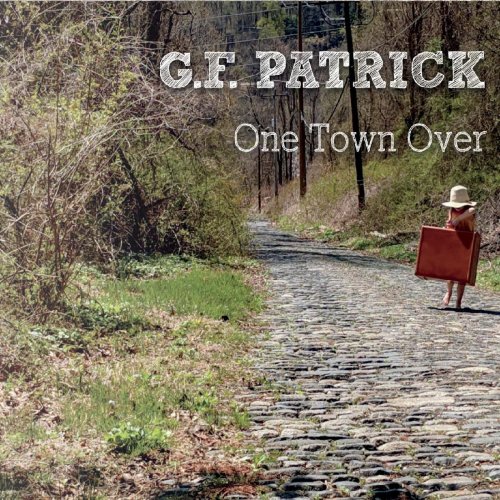

G.F. Patrick - One Town Over (2020)

BAND/ARTIST: G.F. Patrick

- Title: One Town Over

- Year Of Release: 2020

- Label: Need To Know Music/Skunkworks

- Genre: Alt-Country, Folk, Singer/Songwriter

- Quality: 320 / FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 58:03

- Total Size: 141 / 379 Mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

01. Mud (4:48)

02. Trucker's Song (4:18)

03. Refugee's Plea (Jungle Prayer) (4:22)

04. One Town Over (4:02)

05. Tennessee (3:10)

06. Anger of Magdalene (Ain't No Future Workin' 9 to 5) (3:01)

07. Butterfly Effect (3:33)

08. James McGovern (3:23)

09. Blood on the Bottle (3:39)

10. Six-String Directions (4:06)

11. Like Father (4:40)

12. Till the Day We Die (3:54)

13. Beauty Fades (3:24)

14. Water Rising Up (7:43)

01. Mud (4:48)

02. Trucker's Song (4:18)

03. Refugee's Plea (Jungle Prayer) (4:22)

04. One Town Over (4:02)

05. Tennessee (3:10)

06. Anger of Magdalene (Ain't No Future Workin' 9 to 5) (3:01)

07. Butterfly Effect (3:33)

08. James McGovern (3:23)

09. Blood on the Bottle (3:39)

10. Six-String Directions (4:06)

11. Like Father (4:40)

12. Till the Day We Die (3:54)

13. Beauty Fades (3:24)

14. Water Rising Up (7:43)

Born in Georgia and based in Philadelphia, formerly part of Black Horse Motel, G.F. Patrick has a classic Americana twang and drawl to the voice, the music a balance of big guitar swagger and more restrained, softer balladry on songs about everyday people coping with today’s troubled times.

Backed by drummer Billy Conway, Frank Swart on bass and Mark Blasquez on guitars, one of the punchier numbers, Mud, kicks off his debut album with a song about the weight of our dreams and how the pursuit and acquisition of them can sometimes crush us as, in the voice of a man reflecting on his life and marriage, he sings “this town dragged us down, and it made us hurt/And it filled our lives with work/Till this roof weighed like an anchor/And this ring cut like a flint” where “our dreams are mired in the mud” and going off to work is “just a way not to be home”.

Taken at a slower, moodier pace, using imagery of the road, Trucker’s Song recalls how, during his Kindergarten year, the family relocated to Pennsylvania and how the two or three trips back each year made him aware of how distant from home some people lived their lives, the song again reflecting on a growing apart (“wondering when this house stopped feeling home”) and “a love that’s gone before grown old”, with all the loneliness and regret and “the only number/I can’t bring myself to call”.

The first of the acoustic strums, infused with the spirit of Guthrie, Refugee’s Plea (Jungle Prayer) takes a wider perspective as, sung in the voice of a Muslim mother, it sketches the horrors the persecuted endure (“they dogged my freedom down and slaughtered it in the center of town/For all my neighbors to come and see it could happen to them if to me”), losing her children to keep them safe (“lifted my infant up over the wire and lost her into hungry arms”), both in the land they’re forced flee and in the land where they seek shelter. As he puts it in the notes, “The idea that people living in a land of plenty have the right to tell someone else to stay in the hell we’ve helped build for them is infuriating. If we wouldn’t trade places with someone, we shouldn’t be so quick to send them back.”

The title track keeps it reined in and soulful, channelling the likes of Prine and the balladry of Earle on a song about extending the hand of friendship when someone’s in need, finding out what the problem is rather than just standing back and watching. Again, while autobiographically rooted, it plays to Patrick’s storytelling strengths with lyrics like:

You ran from yourself and you ran from me

You ran from your home and from your family

And the last time I saw you there was nothing to say

You moved one town over, and a lifetime away

And I know I judged you,

and I had no place to,

When I didn’t help you.

as he ends with “I’m just one town over, and forgiveness away”.

Picking the tempo back up, the fingerpicked Tennessee jaunts along as the drums and electric guitar kick in, the titular town serving as a metaphor for those dreams we seek but then sometimes settle for those closer to hand (“I turned the car around when you got the mind/Saying one more dream wasn’t what you need/And Philly was close enough to Tennessee”) in order to find happiness.

Adopting a Subterranean Homesick Blues style drive of tumbling lyrics and bustling rhythms, Anger of Magdalene marries social commentary (“Ain’t no future working 9-5 minimum wage in a dead-end job/30 at 15, pregnant at 16, high school dropout could have been the prom queen”) with a murder ballad as our hacked off heroine gets a gun and serves payback on the cop who molested her and a drive-through jerk of a manager.

Returning to a personal note, the Southern bluesy Butterfly Effect relates to the birth of his eldest daughter and wondering what wisdom he could pass on to prepare her for the struggle that lay ahead just for being a woman as “Caught and captured, gussied up and pinned to the wall/They like to come and look at you; compare you all” and how “it’s time to step out of this frame bring forth the hurricane”, a reminder that “it’s the ones who never fought back who are indexed and catalogued/A butterfly with broken wings Is never on display/It’s worth risking your wings to flap them”.

It’s back to storytelling for James McGovern, as, set to rolling Southern blues country, the narrative’s unfolded by an old, former miner who, like his own children, recalls following his father “down into those caves, thought there that I might prove/That I was made of harder stuff than skin and flesh and bone” and how “the first time that I breathed the dark I knew that I was home”, celebrating the “solemn brotherhood among those who dig so deep” while also acknowledging the price paid in the “black lung” to heat others’ homes.

Alcohol-fuelled domestic abuse underpins the deceptively lightly melodic Blood On The Bottle (“when she’s pressed she says she’s clumsy/we both know that weren’t no fall”), sung in the voice of the abuser as they accept what they’ve done (“ I can’t keep her safe/when the booze takes me away”), then, backed by Blasquez’s keys, Six-String Directions again picks up the theme of relationships from the perspective of a lost and beaten down musician (“ you can’t afford to buy new strings/Hell, you can’t afford your beer/And the manager says you ain’t drawn enough to get paid here”) where, back in the motel, it’s a guitar rather than a woman who “always moans on key”.

He hits the final stretch with the echoing twanged guitar rasped delivery of Like Father, a song about battling depression (“the beasts come on you quiet as the grave while you’re speaking/They whisper all those doubts into the places where you fear/ And they steal your joys away, and make it harder every day”), following on with the shuffling brushed snare rhythm and guitar jangle of Till The Day We Die, a song written for a friend suffering a rough patch that, basically, says you can’t know what someone’s going through (“How dare you claim to know me/When I don’t know myself/My reflection is the devil and the mirror is my hell”).

Despite the title, the penultimate Beauty Fades isn’t weighed down with negativity, rather, buoyed by an upbeat melody, its about how, as you grow older (albeit here only 31!), relationships can grow stronger rather than diminish and, if beauty fades, love grows and “the sun still rises and the sun still sets/The flowers still bloom when the snow melts”.

It ends with the gutsy Young-like Water Rising Up, a call for an awakening in a time of environmental crisis and to act while there’s still time, only to then reveal a hidden bonus number, Weep, an aching slow waltz of loss and mortality where he sings “there’s nothing in this heart of mine but hurt and regret” and that “Ain’t nothing in my stomach but whisky and death/And the cancer that eats me, it has a name that’s the same as yours… Call the hurt Matthew a face for the dark when the pain comes/Ask yourself why he is nowhere at all where he used to run”. As that and the others songs suggest, this isn’t an album to fill you with the joys of life, but, between the masterfully crafted and insightful, emotionally resonant lyrics and melodies that linger in your head, it might just well be one that makes you connect with that it means to be human, to have friends, lovers, children, dreams and a heart that can beat as well as be bruised.

Backed by drummer Billy Conway, Frank Swart on bass and Mark Blasquez on guitars, one of the punchier numbers, Mud, kicks off his debut album with a song about the weight of our dreams and how the pursuit and acquisition of them can sometimes crush us as, in the voice of a man reflecting on his life and marriage, he sings “this town dragged us down, and it made us hurt/And it filled our lives with work/Till this roof weighed like an anchor/And this ring cut like a flint” where “our dreams are mired in the mud” and going off to work is “just a way not to be home”.

Taken at a slower, moodier pace, using imagery of the road, Trucker’s Song recalls how, during his Kindergarten year, the family relocated to Pennsylvania and how the two or three trips back each year made him aware of how distant from home some people lived their lives, the song again reflecting on a growing apart (“wondering when this house stopped feeling home”) and “a love that’s gone before grown old”, with all the loneliness and regret and “the only number/I can’t bring myself to call”.

The first of the acoustic strums, infused with the spirit of Guthrie, Refugee’s Plea (Jungle Prayer) takes a wider perspective as, sung in the voice of a Muslim mother, it sketches the horrors the persecuted endure (“they dogged my freedom down and slaughtered it in the center of town/For all my neighbors to come and see it could happen to them if to me”), losing her children to keep them safe (“lifted my infant up over the wire and lost her into hungry arms”), both in the land they’re forced flee and in the land where they seek shelter. As he puts it in the notes, “The idea that people living in a land of plenty have the right to tell someone else to stay in the hell we’ve helped build for them is infuriating. If we wouldn’t trade places with someone, we shouldn’t be so quick to send them back.”

The title track keeps it reined in and soulful, channelling the likes of Prine and the balladry of Earle on a song about extending the hand of friendship when someone’s in need, finding out what the problem is rather than just standing back and watching. Again, while autobiographically rooted, it plays to Patrick’s storytelling strengths with lyrics like:

You ran from yourself and you ran from me

You ran from your home and from your family

And the last time I saw you there was nothing to say

You moved one town over, and a lifetime away

And I know I judged you,

and I had no place to,

When I didn’t help you.

as he ends with “I’m just one town over, and forgiveness away”.

Picking the tempo back up, the fingerpicked Tennessee jaunts along as the drums and electric guitar kick in, the titular town serving as a metaphor for those dreams we seek but then sometimes settle for those closer to hand (“I turned the car around when you got the mind/Saying one more dream wasn’t what you need/And Philly was close enough to Tennessee”) in order to find happiness.

Adopting a Subterranean Homesick Blues style drive of tumbling lyrics and bustling rhythms, Anger of Magdalene marries social commentary (“Ain’t no future working 9-5 minimum wage in a dead-end job/30 at 15, pregnant at 16, high school dropout could have been the prom queen”) with a murder ballad as our hacked off heroine gets a gun and serves payback on the cop who molested her and a drive-through jerk of a manager.

Returning to a personal note, the Southern bluesy Butterfly Effect relates to the birth of his eldest daughter and wondering what wisdom he could pass on to prepare her for the struggle that lay ahead just for being a woman as “Caught and captured, gussied up and pinned to the wall/They like to come and look at you; compare you all” and how “it’s time to step out of this frame bring forth the hurricane”, a reminder that “it’s the ones who never fought back who are indexed and catalogued/A butterfly with broken wings Is never on display/It’s worth risking your wings to flap them”.

It’s back to storytelling for James McGovern, as, set to rolling Southern blues country, the narrative’s unfolded by an old, former miner who, like his own children, recalls following his father “down into those caves, thought there that I might prove/That I was made of harder stuff than skin and flesh and bone” and how “the first time that I breathed the dark I knew that I was home”, celebrating the “solemn brotherhood among those who dig so deep” while also acknowledging the price paid in the “black lung” to heat others’ homes.

Alcohol-fuelled domestic abuse underpins the deceptively lightly melodic Blood On The Bottle (“when she’s pressed she says she’s clumsy/we both know that weren’t no fall”), sung in the voice of the abuser as they accept what they’ve done (“ I can’t keep her safe/when the booze takes me away”), then, backed by Blasquez’s keys, Six-String Directions again picks up the theme of relationships from the perspective of a lost and beaten down musician (“ you can’t afford to buy new strings/Hell, you can’t afford your beer/And the manager says you ain’t drawn enough to get paid here”) where, back in the motel, it’s a guitar rather than a woman who “always moans on key”.

He hits the final stretch with the echoing twanged guitar rasped delivery of Like Father, a song about battling depression (“the beasts come on you quiet as the grave while you’re speaking/They whisper all those doubts into the places where you fear/ And they steal your joys away, and make it harder every day”), following on with the shuffling brushed snare rhythm and guitar jangle of Till The Day We Die, a song written for a friend suffering a rough patch that, basically, says you can’t know what someone’s going through (“How dare you claim to know me/When I don’t know myself/My reflection is the devil and the mirror is my hell”).

Despite the title, the penultimate Beauty Fades isn’t weighed down with negativity, rather, buoyed by an upbeat melody, its about how, as you grow older (albeit here only 31!), relationships can grow stronger rather than diminish and, if beauty fades, love grows and “the sun still rises and the sun still sets/The flowers still bloom when the snow melts”.

It ends with the gutsy Young-like Water Rising Up, a call for an awakening in a time of environmental crisis and to act while there’s still time, only to then reveal a hidden bonus number, Weep, an aching slow waltz of loss and mortality where he sings “there’s nothing in this heart of mine but hurt and regret” and that “Ain’t nothing in my stomach but whisky and death/And the cancer that eats me, it has a name that’s the same as yours… Call the hurt Matthew a face for the dark when the pain comes/Ask yourself why he is nowhere at all where he used to run”. As that and the others songs suggest, this isn’t an album to fill you with the joys of life, but, between the masterfully crafted and insightful, emotionally resonant lyrics and melodies that linger in your head, it might just well be one that makes you connect with that it means to be human, to have friends, lovers, children, dreams and a heart that can beat as well as be bruised.

Year 2020 | Country | Folk | FLAC / APE | Mp3

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads