The history of music is made of ebb and flow. One of the crucial currents of the twentieth century was Neoclassicism, through which composers such as Stravinsky or Prokof’ev distanced themselves from late-Romantic sentimentalism in order to recover a lost essentiality. The Neoclassical way, however, was just one aspect within a larger rediscovery of early music; for the sake of precision, we should also speak of Neo-Baroque, Neo-Renaissance, and even of Neo-Middle-Ages. Twentieth-century composed found their way by rediscovering the musical heritage predating the eighteenth-century Classicism, and managed to detach themselves from their nineteenth-century forebears, and to find a new way to modernity through the revival of a distant past. This new way included, among its most important elements, the retrieval of a harmonic system other than tonality (i.e. modality) and the adoption of a rhythm which tended to transcend bar lines as well as the metrical symmetry which had imposed itself in the eighteenth century.

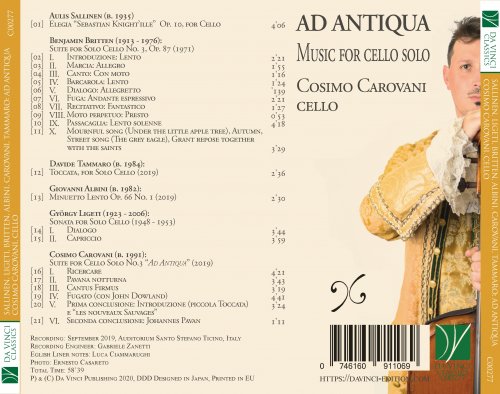

Benjamin Britten, who had an extraordinary musical culture, displays Neo-Renaissance and Neo-Baroque traits in his adoption of musical models from before Classicism, such as John Dowland, Henry Purcell, Georg Friedrich Händel or Johann Sebastian Bach. His fascination for such famous ancestors, however, did never translate into a derivative imitation of melodies or musical materials: rather, Britten took inspiration from compositional techniques. This is evident in his three Cello Suites, whose title immediately makes one think of Bach, but which, in fact, do not contain explicit citations from Bach’s Suites. Moreover, the way they are constructed alludes to the spezzato (“broken”) style of the seventeenth-century lutenists and harpsichordists (with a particular rhythmic freedom due to the habit of arpeggiating the chords) rather than to Bach’s continuous discourse. In the third Suite, the fascination for Russia merges with such models: “I wrote this suite in the early spring of 1971 and took it as a present to Slava Rostropovich when Peter Pears and I visited Moscow and Leningrad in April of that year”; “As a tribute to a great Russian musician and patriot I based this suite on Russian themes: the first three tunes were taken from Tchaikovsky’s volumes of folk-song arrangements; the fourth, the ‘Kontakion’ (Hymn to the Departed), from the English Hymnal [where Orthodox chant is also found] . […] The suite is played without a break and consists of variations on the four Russian tunes”.

The Suite, in nine movements, is a kind of a soul journal, mirroring a declaration of poetics uttered by Britten in a 1964 interview to BBC, whereby he maintained that he did not feel an inclination for the larger ensembles, but rather for the small-scale works, so that he could control the sound more precisely, fine-tune his works and listen in detail.

In this Suite, the cello is treated as an intimate voice, at times human, at time hellish or heavenly; the work opens with a Lento, a kind of solemn Overture grounded precisely on that funeral hymn called Kontakion. A solitary pizzicato, followed by silence, acts almost as an obsessive bourdon bass against a tune developed in the medium-low register, in an atmosphere which is both tortured and mystical at the same time. The March, on Tchaikovsky’s themes, begins as a kind of horse-ride, in a quick dotted rhythm. However, the style – rhapsodic and fragmented, full of meaningful rests – distances itself totally from its nineteenth-century models. Sudden oases of contemplation interrupt the harsh, at times purposefully violent character of this dance. The following Con moto reassumes the March’s closing motif, underpinning the organic nature of this Suite, which is interwoven of themes responding to each other from one dance to another. The character is legato, mellow, but never really calm: there is constantly a feeling of the Unheimlich (Freud’s “uncanny”), which Britten shared with Šostaković (for whom, not by chance, Britten had this Suite performed during his USSR tour). Arpeggio figurations reminiscent of those opening Bach’s First Suite inaugurate the fourth piece, a Barcarola whose reference to water (far from being a pictorial evocation of the Venetian landscape) seems to have an archetypal value: the Baroque style becomes therefore almost an amniotic fluid. But water, just as in Schubert (a fundamental composer for Britten) does not represent merely birth and life. The central climax, of an agitated and almost gasping nature, refers to the idea of danger and death. In the following Allegretto, a dialogue is built between the pizzicato phrases (soft, almost lute-like) and those played with the bow (more incisive and imposing). An unusual Fugue follows: rather than referring to the abstract and Pythagorean character of form, Britten creates a counterpoint imbibed by an effusive lyricism. The following recitativo (Fantastico) opens instead with short and impulsive gestures; the discourse is rhapsodic and unforeseeable: high-pitched outbursts alternate with pizzicatos, tremolos, arpeggios, flageolets and glissandos. Fragments from popular nursery tunes emerge in alternation with almost rabid moments. After a Moto perpetu (Perpetuum mobile) within which, in Bach’s style, a principal voice surfaces, the Passacaglia (Passecaille) gives life to a new dialogue between a medium voice (human-like, as if pleading) and a lower one (darker, infernal). The finale (Grant repose together with the Saints) seems to finally attain a placid, consonant serenity; however, after a cheerful popular tune, the instrument’s voice darkens once more. The Suite closes on an almost “white” sound, dumbfounded, with vanishing bichords which mark the steps of a modern Wanderer.

Written between 1948 and 1953, Ligeti’s Cello Sonata was initially scorned by the Soviet Union of the Composers, which forbade its performance deeming it to be “exceedingly modern”: only in the Eighties was it rediscovered, entering the cellists’ repertoire. The first movement, Dialogo, was written in 1948 for a female student of the Liszt Academy of Budapest, Annuss Virány, with whom Ligeti had secretly fallen in love. In 1953 another cellist, Vera Dénes, asked Ligeti for a solo cello piece: the composer thus had the idea of adding a Capriccio to the Dialogo, thus fashioning a short Sonata in two movements. Dialogo, in Ligeti’s own words, is “a dialogue. Because it’s like two people, a man and a woman, conversing. I used the C string, the G string and the A string separately… I had been writing much more ‘modern’ music in 1946 and 1947, and then in ’48 I began to feel that I should try to be more ‘popular’… I attempted in this piece to write a beautiful melody, with a typical Hungarian profile, but not a folksong… or only half, like in Bartók or in Kodály—actually, closer to Kodály”.

Adagio, rubato, cantabile: this movement opens with two double-stop pizzicatos separated by a glissando. A melody then surfaces, in alternation with pizzicato sequences. Ligeti alludes to harmonies from before the Classical era, in particular to the Dorian and Phrygian modes. A feeling of mystery hovers on the dialogue, which becomes increasingly rich in pathos, ending on an unexpected and serene Picardy third. The second movement, Capriccio, is (in the composer’s words), “a virtuoso piece in my later style that is closer to Bartók. I was 30 years old when I wrote it. I loved virtuosity and took the playing to the edge of virtuosity much like [Paganini]”. The shooting figurations, of a Toccata-like character (Presto con slancio) do not, however, form a traditional perpetuum mobile: the discourse is interspersed with rests, turning virtuosity almost to a metaphor of folly, rather than to a state of euphoric certainty. A general demonic inspiration is evident also in the use of tritones (Diabolus in musica). Ligeti takes inspiration from antiquity in the polyphonic figurations moulded on Bach, with a repeated note and another forming an internal melody, but he also uses new techniques, such as the “tremolo sul tasto”. Sudden lyrical openings are constantly interrupted by brusque and vehement gestures, in a discourse which gets increasingly feverish and agitated. The piece seems almost to close on an ambiguous sound rarefaction, but suddenly the Coda affirms with exuberance (“con tutta la forza”) an unexpected and triumphant G-major.

The Suite III “Ad Antiqua” by Cosimo Carovani renews the twentieth-century interest in the recourse to pre-Classical forms, while adapting it to today’s sensitivity. The evocation of Renaissance music is evident from the outset: the form of the Ricercare refers to the emancipation of instrumental music in the sixteenth century, while keeping in mind that it was modelled on pre-existing vocal music (motets and madrigals). The cello is almost a human voice but, as in Britten and Ligeti, it may also become something else. The beginning, in low-register double stops, is almost a kind of bourdon: in spite of the low pitches, the atmosphere is not dark, but rather mystical, as if in an Orthodox chant. The austere atmosphere is broken by a kind of Frescobaldi-like improvisation, with furious scales. The climax reaches its apex in the upper register; later it goes back to the lower, with a final episode which seems to allude to polyphonic Ricercari (Gabrieli’s first and foremost). With the Pavana notturna, we enter a world of sound refinement where the echoes of Marin Marais or Sainte-Colombe are found, along with the inquietudes of contemporaneity: without falling into hedonism, Carovani recovers the enjoyment of the present moment, free from any post-modern cynicism. The references to the past are affectionately spun, without parodying. A very low fundamental bass opens the Cantus firmus, on which a melodic line is rooted, starting with a glissando and portraying a climate of mystery and expectation. The use of unconventional, extended techniques, both on the strings and using the performer’s actual voice, seems to blend sound with singing. Music seems to evade the appointed tracks (de-lirium) and to express superhuman forces, between Eros and Thanatos, with episodes which appear to allude to extra-European and Eastern suggestions. The Fugato, inspired by John Downland, brings us back to a contemplative dimension, in which the challenge of performing polyphony on a usually monodic instrument seems to become the metaphor for an interior discipline. The beginning is austere and essential, and later the scoring thickens and conquers the high register. The impression of serenity and order is radically broken by a violent gesture. The finale’s title, Introduzione (Piccola Toccata) e Les Nouveaux Sauvages alludes to a famous movement of Rameau’s Les Indes Galantes. But, as in Britten’s case, Carovani carefully avoids all explicit citations. If Rameau’s Sauvages, though inspired by the Louisiana natives’ dances, were grounded on the French Baroque idiosyncrasies, these “new savages” bring the Dionysian aspect to an extreme, being fathered by the twentieth century, when the culture of the body exploded.

The Introduction opens with a wide gesture, almost in the style of a French Overture, and continues with a Toccata-like episode dominated by a feeling of wonder and improvisation. So, the Suite closes, or perhaps not: in fact, Carovani adds a second, aphorism-like ending, the Johannes Pavan, whose delicate pizzicatos transmit an atmosphere of intimism, as if we could hear the string’s light breathing.

The reconsideration of the eighteenth century is at the roots of the Minuetto lento op. 66 no. 1 by Giovanni Albini. Only the vestiges are left of what was the original dance: the song prevails, legato, with the instrument’s dark voice, which seems almost to overturn the gallant conventions of the eighteenth century, by putting its sensuousness into relief. Davide Iammaro’s Toccata opens with isolated pizzicatos and glissandos, separated by short rhythmical-melodic motifs; once more, the style of Toccata leads to a discursive freedom whereby melos alternates with episodes with a more pronounced rhythmic and virtuoso character.

The Elegia Sebastian Knigh’ille by the Finn Aulis Sallinen brings us back to a gloomy and mysterious climate, interspersed by silences which are no less important than the sounds. Among solitary pizzicatos, harsh bichords and throbbing tremolos, the music juxtaposes contemplation with an inexhaustible vitality. Among the various motifs-gestures, a sinuous melody affirms itself, becoming increasingly intense and flowing into vehement repeated notes. Pianissimo pizzicatos follow, gradually assuaging the mood, in a rarefaction which steadily leads to silence.

Liner notes by Luca Ciammarughi