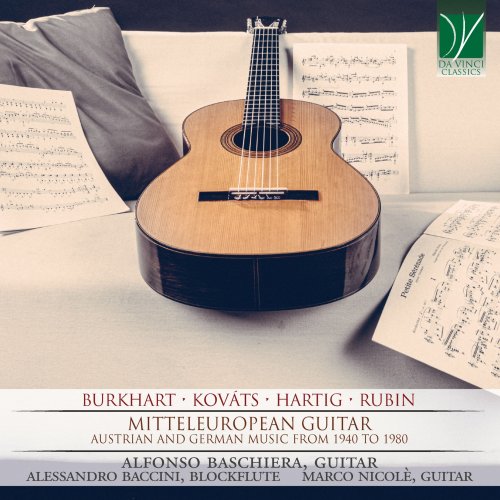

Alfonso Baschiera, Marco Nicolé, Alessandro Baccini - Burkhart, Kovats, Hartig, Rubin: Mitteleuropean Guitar (Austrian and German Music from 1940 to 1980) (2020)

BAND/ARTIST: Alfonso Baschiera, Marco Nicolé, Alessandro Baccini

- Title: Burkhart, Kovats, Hartig, Rubin: Mitteleuropean Guitar (Austrian and German Music from 1940 to 1980)

- Year Of Release: 2020

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical Guitar

- Quality: flac lossless

- Total Time: 00:53:17

- Total Size: 244 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Passacaglia (For Guitar)

02. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 1, Perfect Fifths

03. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 2, Three Chord Stops

04. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 3, Homage

05. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 4, Pendular Movement

06. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 5, Whistle

07. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 6, Octaves

08. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 7, Mini-Toccata

09. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 8, Waltz?

10. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 9, Estilo popular

11. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 10, Twilight

12. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 11, Study (For 2 Guitars)

13. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 12, Two Early Melodies (For 2 Guitars)

14. Fünf Stuke fur Blockflöte und Gitarre, Op. 25: No. 1, Andantino

15. Fünf Stuke fur Blockflöte und Gitarre, Op. 25: No. 2, Allegretto con moto e grazioso

16. Fünf Stuke fur Blockflöte und Gitarre, Op. 25: No. 3, Allegro

17. Fünf Stuke fur Blockflöte und Gitarre, Op. 25: No. 4, Andante

18. Fünf Stuke fur Blockflöte und Gitarre, Op. 25: No. 5, Vivace

19. Drei Stücke, Op. 26: No. 1, Capriccio

20. Drei Stücke, Op. 26: No. 2, Thema mit Variationen

21. Drei Stücke, Op. 26: No. 3, Alla Danza

22. Minutenstüke: No. 1, Moderato, un poco agitato

23. Minutenstüke: No. 2, Leggiero, molto legando

24. Minutenstüke: No. 3, Andantino

25. Minutenstüke: No. 4, Vivo, ritmico

26. Minutenstüke: No. 5, Tranquillamente scorrendo

27. Minutenstüke: No. 6, Non troppo allegro

28. Petite Sérénade pour Guitare: I. Andante

29. Petite Sérénade pour Guitare: II. Allegro con brio

From the Classical era until the early twentieth century, Vienna, Salzburg and Berlin have represented the throbbing heart of art music. Within little more than a century, in their famous theatres, a listener could have witnessed the solidification of the tonal system and its later disintegration. By the late Twenties, that same listener – already stunned by such changes – could have heard the most disparate languages: from the rigorous choices of dodecaphony to those of the epigones of Impressionism, from the most reassuring late-Romantic Symphonies to the subtle elaborations of the popular fabric of the East-European countries’ music. So varied was the supply available to our listener that it was difficult to choose a clear direction, and this applied to both the young composers and the performers, who had to select their repertoire with an eye to the audience’s reception.

In this very unstable and uncertain context, the great Andrés Segovia began to perform in the most important concert halls worldwide, leading to success a whole series of composers (Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Ponce, Turina, Moreno-Torroba, Rodrigo, Tansman) whose works are frequently defined as “the Segovian repertoire”. Most guitarists were later educated on these same works, neglecting other composers of a non-secondary importance, who, until present-day, have not reached a comparable fame.

This is the case with Franz Burkhart, who wrote Passacaglia, one of his most important works for solo guitar, in the midst of the Second World War. Just a few years before, in 1935, he had received an important Prize of Composition at the World Fair of Brussels, followed, a few years later, by the Prize of the Vienna Musikfreunde. Following a scheme which had become common fare in the Baroque era, the piece opens with a theme (made of the typical eight bars) which is reiterated throughout the eighteen variations following it. After an initial process of rhythmic accumulation, the composer abandons himself to variations (at times lyrical, at times passionate, at times rough), in a pressing sequence of fragments leading to the well-deserved final repose. The composer’s scoring does not distance itself from the usual tonal formulae, whereas later, in works such as Suite I, Suite II and some works for guitar duet, he would constantly recur to dissonances and cromaticism.

Just a few years before, in 1937, a young student by the name of Barna Kovats, who was seventeen at the time, was deeply impressed by a recital by Segovia, and decided, without further delay, to dedicate his entire activity as a composer, performer and teacher to the guitar. The catalogue of his works for and with guitar is abundant and varied, comprising a Concerto for guitar and strings as well as important pedagogical collections, along with chamber music. Compelled to emigrate to South America in 1956, Kovats came back to Europe a few years later, choosing Salzburg as his place of residence and settling there, where he would remain as a Professor of guitar at the Mozarteum. His activity in favour of the appreciation of the folk repertoire, elaborated and digested through a very personal use of technique, points out the fact that Kovats was for guitar what Bartók was for the piano. It is particularly in the small-scale endeavours, or, rather, on the so-called “perfect miniatures” (i.e. musical inventions condensed in the smallest possible space) that Kovats left his most clear imprint, so as to earn the well-known praise by Frank Martin, who wrote: “How can you say so much in so short a time?” (letter from Martin to Kovats). As happens in a short Sonata-form development, in the Minutenstücke a small fragment suffices for letting the material needed for a piece’s elaboration flow. Frequently the open strings are knowledgeably inserted within the harmonic fabric, generating particular sonorities known only to those who possess a deep knowledge of guitar technique and scoring. Otherwise, in the beautiful Short Studies Vol. II, the folkloric element at times generates the thematic cells, at times inserts itself between the phrases, leading the listener back to the essence of Hungarian music: i.e. singing.

A harpsichordist and composer, who was best known for his choral works, Heinz Friedrich Hartig taught since 1948 at the Berliner Hochschule für Musik; among his students was also the Italian Carlo Domeniconi. Hartig is represented, along with Bussotti and Castelnuovo-Tedesco, in a Deutsche-Grammophon production of 1971, which was as important as it was innovative; here, Siegfried Behrend recorded his Perché op. 28 for guitar and choir. His most important work is the Suite concertante op. 19, one of the few works scored for guitar and winds, where the composer was able to maintain a seldom-found balance of sound between guitar, winds and brass.

The Fünf Stücke für Blockflöte und Gitarre op. 25, written in 1956, are an experiment in the felicitous pairing of guitar and recorder, making a fascinating though delicate combination; the two instruments enter into a dialogue of peers, without needing to force their volume of sound. The most interesting element is rhythm, with ternary figurations over binary structures, creating particular movements, typical for Prokofjev’s music.

In the Drei Stücke für Gitarre op. 26 Hartig offers us a Suite with a perfect guitar scoring. It is an itinerary where the composer goes from the affirmation of the tonal chromaticism in the initial Capriccio, up to the explicit adhesion to the serial forms in the Thema mit Variationen (where, though, serialism is denied in the final consonant chords) and in the following Alla Danza. We have the impression of a translation toward a language which is never entirely embraced, an acceptance of serialism which is not entirely accomplished.

Having composed no less than ten Symphonies written between 1928 and 1986, the Viennese Marcel Rubin (a former student of Darius Milhaud) wrote a single piece for the guitar, as happened to many other composers of this time. In his Petite Sérénade, the dense and thoughtful traits of the first movement emerge in contrast with the joking whim of the successive Allegro con brio, where Rubin successfully experiments with all registers of the guitar, while painting a colourful sketch characterized by sudden mood swings.

The composers presented in this album will possibly never achieve, among the guitarists, a fame comparable to that of Castelnuovo-Tedesco or Rodrigo; however, their music deserves an adequate (re)positioning within the twentieth-century repertoire; in particular, a careful study of the entire corpus of the works with guitar by Barna Kovats and Franz Burkhart (which are still largely unexplored) could highlight these important composers afresh.

01. Passacaglia (For Guitar)

02. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 1, Perfect Fifths

03. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 2, Three Chord Stops

04. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 3, Homage

05. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 4, Pendular Movement

06. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 5, Whistle

07. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 6, Octaves

08. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 7, Mini-Toccata

09. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 8, Waltz?

10. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 9, Estilo popular

11. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 10, Twilight

12. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 11, Study (For 2 Guitars)

13. Short Studies Vol. II: No. 12, Two Early Melodies (For 2 Guitars)

14. Fünf Stuke fur Blockflöte und Gitarre, Op. 25: No. 1, Andantino

15. Fünf Stuke fur Blockflöte und Gitarre, Op. 25: No. 2, Allegretto con moto e grazioso

16. Fünf Stuke fur Blockflöte und Gitarre, Op. 25: No. 3, Allegro

17. Fünf Stuke fur Blockflöte und Gitarre, Op. 25: No. 4, Andante

18. Fünf Stuke fur Blockflöte und Gitarre, Op. 25: No. 5, Vivace

19. Drei Stücke, Op. 26: No. 1, Capriccio

20. Drei Stücke, Op. 26: No. 2, Thema mit Variationen

21. Drei Stücke, Op. 26: No. 3, Alla Danza

22. Minutenstüke: No. 1, Moderato, un poco agitato

23. Minutenstüke: No. 2, Leggiero, molto legando

24. Minutenstüke: No. 3, Andantino

25. Minutenstüke: No. 4, Vivo, ritmico

26. Minutenstüke: No. 5, Tranquillamente scorrendo

27. Minutenstüke: No. 6, Non troppo allegro

28. Petite Sérénade pour Guitare: I. Andante

29. Petite Sérénade pour Guitare: II. Allegro con brio

From the Classical era until the early twentieth century, Vienna, Salzburg and Berlin have represented the throbbing heart of art music. Within little more than a century, in their famous theatres, a listener could have witnessed the solidification of the tonal system and its later disintegration. By the late Twenties, that same listener – already stunned by such changes – could have heard the most disparate languages: from the rigorous choices of dodecaphony to those of the epigones of Impressionism, from the most reassuring late-Romantic Symphonies to the subtle elaborations of the popular fabric of the East-European countries’ music. So varied was the supply available to our listener that it was difficult to choose a clear direction, and this applied to both the young composers and the performers, who had to select their repertoire with an eye to the audience’s reception.

In this very unstable and uncertain context, the great Andrés Segovia began to perform in the most important concert halls worldwide, leading to success a whole series of composers (Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Ponce, Turina, Moreno-Torroba, Rodrigo, Tansman) whose works are frequently defined as “the Segovian repertoire”. Most guitarists were later educated on these same works, neglecting other composers of a non-secondary importance, who, until present-day, have not reached a comparable fame.

This is the case with Franz Burkhart, who wrote Passacaglia, one of his most important works for solo guitar, in the midst of the Second World War. Just a few years before, in 1935, he had received an important Prize of Composition at the World Fair of Brussels, followed, a few years later, by the Prize of the Vienna Musikfreunde. Following a scheme which had become common fare in the Baroque era, the piece opens with a theme (made of the typical eight bars) which is reiterated throughout the eighteen variations following it. After an initial process of rhythmic accumulation, the composer abandons himself to variations (at times lyrical, at times passionate, at times rough), in a pressing sequence of fragments leading to the well-deserved final repose. The composer’s scoring does not distance itself from the usual tonal formulae, whereas later, in works such as Suite I, Suite II and some works for guitar duet, he would constantly recur to dissonances and cromaticism.

Just a few years before, in 1937, a young student by the name of Barna Kovats, who was seventeen at the time, was deeply impressed by a recital by Segovia, and decided, without further delay, to dedicate his entire activity as a composer, performer and teacher to the guitar. The catalogue of his works for and with guitar is abundant and varied, comprising a Concerto for guitar and strings as well as important pedagogical collections, along with chamber music. Compelled to emigrate to South America in 1956, Kovats came back to Europe a few years later, choosing Salzburg as his place of residence and settling there, where he would remain as a Professor of guitar at the Mozarteum. His activity in favour of the appreciation of the folk repertoire, elaborated and digested through a very personal use of technique, points out the fact that Kovats was for guitar what Bartók was for the piano. It is particularly in the small-scale endeavours, or, rather, on the so-called “perfect miniatures” (i.e. musical inventions condensed in the smallest possible space) that Kovats left his most clear imprint, so as to earn the well-known praise by Frank Martin, who wrote: “How can you say so much in so short a time?” (letter from Martin to Kovats). As happens in a short Sonata-form development, in the Minutenstücke a small fragment suffices for letting the material needed for a piece’s elaboration flow. Frequently the open strings are knowledgeably inserted within the harmonic fabric, generating particular sonorities known only to those who possess a deep knowledge of guitar technique and scoring. Otherwise, in the beautiful Short Studies Vol. II, the folkloric element at times generates the thematic cells, at times inserts itself between the phrases, leading the listener back to the essence of Hungarian music: i.e. singing.

A harpsichordist and composer, who was best known for his choral works, Heinz Friedrich Hartig taught since 1948 at the Berliner Hochschule für Musik; among his students was also the Italian Carlo Domeniconi. Hartig is represented, along with Bussotti and Castelnuovo-Tedesco, in a Deutsche-Grammophon production of 1971, which was as important as it was innovative; here, Siegfried Behrend recorded his Perché op. 28 for guitar and choir. His most important work is the Suite concertante op. 19, one of the few works scored for guitar and winds, where the composer was able to maintain a seldom-found balance of sound between guitar, winds and brass.

The Fünf Stücke für Blockflöte und Gitarre op. 25, written in 1956, are an experiment in the felicitous pairing of guitar and recorder, making a fascinating though delicate combination; the two instruments enter into a dialogue of peers, without needing to force their volume of sound. The most interesting element is rhythm, with ternary figurations over binary structures, creating particular movements, typical for Prokofjev’s music.

In the Drei Stücke für Gitarre op. 26 Hartig offers us a Suite with a perfect guitar scoring. It is an itinerary where the composer goes from the affirmation of the tonal chromaticism in the initial Capriccio, up to the explicit adhesion to the serial forms in the Thema mit Variationen (where, though, serialism is denied in the final consonant chords) and in the following Alla Danza. We have the impression of a translation toward a language which is never entirely embraced, an acceptance of serialism which is not entirely accomplished.

Having composed no less than ten Symphonies written between 1928 and 1986, the Viennese Marcel Rubin (a former student of Darius Milhaud) wrote a single piece for the guitar, as happened to many other composers of this time. In his Petite Sérénade, the dense and thoughtful traits of the first movement emerge in contrast with the joking whim of the successive Allegro con brio, where Rubin successfully experiments with all registers of the guitar, while painting a colourful sketch characterized by sudden mood swings.

The composers presented in this album will possibly never achieve, among the guitarists, a fame comparable to that of Castelnuovo-Tedesco or Rodrigo; however, their music deserves an adequate (re)positioning within the twentieth-century repertoire; in particular, a careful study of the entire corpus of the works with guitar by Barna Kovats and Franz Burkhart (which are still largely unexplored) could highlight these important composers afresh.

Year 2020 | Classical | Instrumental | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads