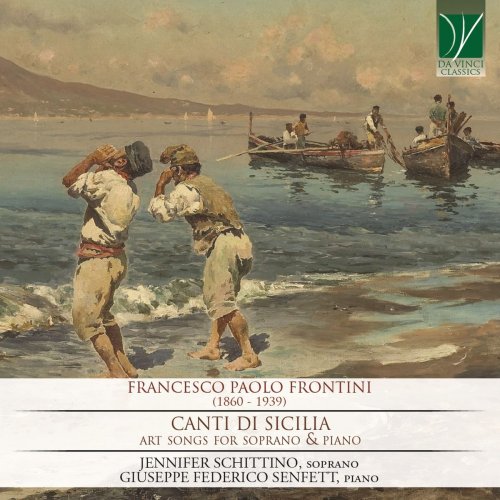

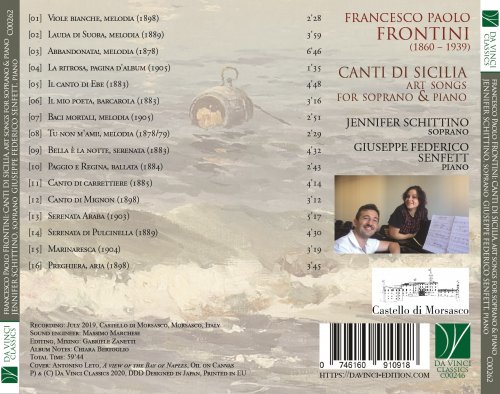

Jennifer Schittino - Giovanni Paolo Frontini: Canti di Sicilia (Art Songs for Soprano & Piano) (2020)

BAND/ARTIST: Jennifer Schittino

- Title: Giovanni Paolo Frontini: Canti di Sicilia (Art Songs for Soprano & Piano)

- Year Of Release: 2020

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 59:35 min

- Total Size: 204 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

01. Viole bianche

02. Lauda di Suora

03. Abbandonata!

04. La ritrosa

05. Canto Ebe

06. Il mio poeta

07. Baci mortali

08. Tu non m'ami!

09. Bella è la notte

10. Paggio e Regina

11. Canto di carrettiere (dal Don Joan)

12. Canto Mignon

13. Serenata Araba

14. Serenata di Pulcinella

15. Marinaresca

16. Preghiera, dall'opera Malìa atto II

Sicily is a self-contained world; a microcosm where breath-taking landscapes (from the sea to the Mount Etna, a spectacular volcano, from the fertile gardens to the steep hills) frame a culture boasting several millennia of glorious history; a place where virtually all of the Mediterranean cultures meet, bringing along their own history, their languages, their forms of art, their religions. Sicily is justly proud of a glorious past and of an identity like no other; it resists all attempts to be tamed, and while it welcomes the foreigners and visitors with cordiality, it also defies all stereotypes.

Due to its complex history, where the presence of the Greeks was followed by countless dominations (including such disparate cultures as the Arabs and the Normans), also the music of Sicily is encrusted with a variety of influences, which are not simply juxtaposed to each other in a forced or heterogeneous fashion, but rather enliven each other and confer to the invaders’ tunes some new qualities. The rich Sicilian heritage of orally transmitted music is thus almost the living memory of a mosaic of cultures, hiding itself in tunes which are quintessentially Mediterranean, and yet frequently impossible to define.

And along with the enrapturing beauty of the omnipresent popular singing, with its ancient roots and its always renewed appearance, there is the rich repertoire of “classical” music, the music of the urban medium and upper classes, who profited from their continuous contact with the aristocratic salons of the great rulers, and who enjoyed music-making as much as did their rural counterparts. Numerous operatic theatres blossomed throughout the island, ranging from the most imposing temples of the voice (such as the Teatro Massimo of Palermo) to the tiniest theatres in the small towns of the island’s interior.

This was the fertile ground in which the life and art of Francesco Paolo Frontino blossomed, and from which he drew the life and soul of his creative output. This loyal son of his homeland, born in the beautiful city of Catania in 1860, seems however slightly to betray his origins when one considers three of the numerous pen-names he adopted for his compositional activity: if “Onorato Piccini” still sounds very Italian (though not immediately recognizable as Sicilian), certainly the bizarre name of “Franz Gotthardmann” and the French-sounding “Oscar Fleuranges” will hardly suggest to the reader an association with the southernmost region of Italy. However, they do reveal that, while Frontini was keenly and proudly bound to his homeland and to its musical history, he was also very skilled in the European compositional techniques. He was a very cultivated man, both as concerns music proper and in other fields of the human knowledge; and the influence of the Northern traditions of “art songs” for voice and piano is clearly discernible in many of his own numerous songs. Their social setting was typically that of the bourgeois and aristocratic salons, where the long Sicilian evenings could be spent in leisurely activities and in a pleasurable music-making. Similar to the Sicilian folksongs, they speak of love in all of its forms (from the jokes of courtship to the tragedies of jealousy), of life, of the great emotions and of the trifling aspects of life.

Frontini’s first approaches to music were encouraged by his father, Martino, who had been the founder and the conductor of the Civic Band of Catania for thirty-seven years; Francesco Paolo studied violin and later composition at the Conservatories of Palermo and Naples. His first compositional attempts took place within the framework of sacred music (notably with a Requiem dedicated to the memory of Pietro Antonio Coppola, who had been the first to conduct one of Frontini’s youthful sacred works). Later, Frontini established a successful career as an operatic composer: his first opera, Nella, written when he was just twenty-one, was an immediate success, and it brought the young composer’s figure to the attention of the press. The following two operas, Sansone and Aleramo followed soon, in consecutive years, while the next one, Malia (1893), would definitively establish Frontini as a leading figure in the musical panorama. Malia, possibly Frontini’s masterpiece, was set to a libretto by Luigi Capuana, one of the greatest Sicilian authors of the nineteenth century, and one who was able to portray very faithfully, and yet very poetically, the complexity of Sicily’s society, of its traditions and also of its myths and fairy tales. Intriguingly, Malia was written by Capuana at first as the opera libretto, then as a comedy in Italian, and then (nearly ten years later) as a comedy in Sicilian (in spite of Giovanni Verga’s misgivings). From Malia, Frontini excerpted the touching Preghiera (Prayer), a typical example of the intertwining of the sacred with the theatrical in his oeuvre (as in that of many other Italian operatic composers of the era).

The beautiful collection of songs recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album is very representative of the composer’s felicitous melodic vein and of the variety of the moods he could evoke, as well as of the number of literary sources he drew from. His knowledge of the European trends is demonstrated by his setting of lyrics by Heinrich Heine, in Tu non m’ami (the original German poem is Du liebst mich nicht); and if Frontini was acquainted with the work of some of the leading authors of the era, several of them, in turn, were acquainted with his output. A musician such as Massenet admitted that he became “ecstatic” when he could listen to Frontini’s music; but among his many admirers were also Victor Hugo, Emile Zola and Giacomo Puccini. In Tu non m’ami, the playful style of the initial section is followed by a more expressive mood, whose lavish accompaniment is built on generous harmonic connections.

Curiously enough, a much more sensual style is found in Lauda di suora (“A Nun’s Song”): even though the general tone is religious, and the words evoke a contemplation of the Crucifix, the music is unmistakably earthly, with its complex chordal progressions and wide melodic range. These choices befit the lyrics, written by Mario Rapisardi, a controversial Sicilian poet who was openly at war with all kinds of authorities, including the religious ones; thus, it comes as no surprise that another of the songs recorded here, Il canto di Ebe, is excerpted from Rapisardi’s Lucifero (a work explicitly condemned by the Archbishop of Catania).

While he was deeply rooted in his Sicilian heritage, Frontini was also interested in musical exoticism, frequently imagined as the ideal setting for adventurous love stories. For example, one of his best-known songs is Serenata araba, about which it was written (in 1953, by Domenico Danzuso): “It represents a small jewel of unsurpassable value, and it demonstrates the genius of an artist who, even though he did not know the East, was still able to fully express its spirit, by writing the most beautiful Arabian music”. Another serenade recorded here is equally delightful, though with a very different style: La serenata di Pulcinella (“Punch’s serenade”) wavers between irony and tenderness, employing features genuinely excerpted from the spontaneous musicianship of Southern Italy, while also transforming them into a very refined musical work (through a knowledgeable use of harmony and onomatopoeias).

Similar traits are found also in other of his songs: for example, Canto di carrettiere and Marinaresca focus on particular human and social situations, as well as on special “landscapes” and natural contexts, and while they depict faithfully and effectively the lively scenes they promise, they never lack a touch of human sympathy and feeling.

These characteristics are possibly the most fascinating and frequently found in Frontini’s large output of songs: even when the lyrics are rather simple, and merely suggestive of love stories hinted at, rather than properly narrated, the music gives depth to the texts and it brings to life the human traits of the hidden protagonists.

In this perhaps lies Frontini’s genius, and the true worth of his music: by listening to it, the world he lived in and portrayed in his music comes to life once more, and we are brought, by the notes of his music, in another time and another place, tinged with nostalgia, magic and the enchantment of the unknown.

Album Notes by Chiara Bertoglio

Due to its complex history, where the presence of the Greeks was followed by countless dominations (including such disparate cultures as the Arabs and the Normans), also the music of Sicily is encrusted with a variety of influences, which are not simply juxtaposed to each other in a forced or heterogeneous fashion, but rather enliven each other and confer to the invaders’ tunes some new qualities. The rich Sicilian heritage of orally transmitted music is thus almost the living memory of a mosaic of cultures, hiding itself in tunes which are quintessentially Mediterranean, and yet frequently impossible to define.

And along with the enrapturing beauty of the omnipresent popular singing, with its ancient roots and its always renewed appearance, there is the rich repertoire of “classical” music, the music of the urban medium and upper classes, who profited from their continuous contact with the aristocratic salons of the great rulers, and who enjoyed music-making as much as did their rural counterparts. Numerous operatic theatres blossomed throughout the island, ranging from the most imposing temples of the voice (such as the Teatro Massimo of Palermo) to the tiniest theatres in the small towns of the island’s interior.

This was the fertile ground in which the life and art of Francesco Paolo Frontino blossomed, and from which he drew the life and soul of his creative output. This loyal son of his homeland, born in the beautiful city of Catania in 1860, seems however slightly to betray his origins when one considers three of the numerous pen-names he adopted for his compositional activity: if “Onorato Piccini” still sounds very Italian (though not immediately recognizable as Sicilian), certainly the bizarre name of “Franz Gotthardmann” and the French-sounding “Oscar Fleuranges” will hardly suggest to the reader an association with the southernmost region of Italy. However, they do reveal that, while Frontini was keenly and proudly bound to his homeland and to its musical history, he was also very skilled in the European compositional techniques. He was a very cultivated man, both as concerns music proper and in other fields of the human knowledge; and the influence of the Northern traditions of “art songs” for voice and piano is clearly discernible in many of his own numerous songs. Their social setting was typically that of the bourgeois and aristocratic salons, where the long Sicilian evenings could be spent in leisurely activities and in a pleasurable music-making. Similar to the Sicilian folksongs, they speak of love in all of its forms (from the jokes of courtship to the tragedies of jealousy), of life, of the great emotions and of the trifling aspects of life.

Frontini’s first approaches to music were encouraged by his father, Martino, who had been the founder and the conductor of the Civic Band of Catania for thirty-seven years; Francesco Paolo studied violin and later composition at the Conservatories of Palermo and Naples. His first compositional attempts took place within the framework of sacred music (notably with a Requiem dedicated to the memory of Pietro Antonio Coppola, who had been the first to conduct one of Frontini’s youthful sacred works). Later, Frontini established a successful career as an operatic composer: his first opera, Nella, written when he was just twenty-one, was an immediate success, and it brought the young composer’s figure to the attention of the press. The following two operas, Sansone and Aleramo followed soon, in consecutive years, while the next one, Malia (1893), would definitively establish Frontini as a leading figure in the musical panorama. Malia, possibly Frontini’s masterpiece, was set to a libretto by Luigi Capuana, one of the greatest Sicilian authors of the nineteenth century, and one who was able to portray very faithfully, and yet very poetically, the complexity of Sicily’s society, of its traditions and also of its myths and fairy tales. Intriguingly, Malia was written by Capuana at first as the opera libretto, then as a comedy in Italian, and then (nearly ten years later) as a comedy in Sicilian (in spite of Giovanni Verga’s misgivings). From Malia, Frontini excerpted the touching Preghiera (Prayer), a typical example of the intertwining of the sacred with the theatrical in his oeuvre (as in that of many other Italian operatic composers of the era).

The beautiful collection of songs recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album is very representative of the composer’s felicitous melodic vein and of the variety of the moods he could evoke, as well as of the number of literary sources he drew from. His knowledge of the European trends is demonstrated by his setting of lyrics by Heinrich Heine, in Tu non m’ami (the original German poem is Du liebst mich nicht); and if Frontini was acquainted with the work of some of the leading authors of the era, several of them, in turn, were acquainted with his output. A musician such as Massenet admitted that he became “ecstatic” when he could listen to Frontini’s music; but among his many admirers were also Victor Hugo, Emile Zola and Giacomo Puccini. In Tu non m’ami, the playful style of the initial section is followed by a more expressive mood, whose lavish accompaniment is built on generous harmonic connections.

Curiously enough, a much more sensual style is found in Lauda di suora (“A Nun’s Song”): even though the general tone is religious, and the words evoke a contemplation of the Crucifix, the music is unmistakably earthly, with its complex chordal progressions and wide melodic range. These choices befit the lyrics, written by Mario Rapisardi, a controversial Sicilian poet who was openly at war with all kinds of authorities, including the religious ones; thus, it comes as no surprise that another of the songs recorded here, Il canto di Ebe, is excerpted from Rapisardi’s Lucifero (a work explicitly condemned by the Archbishop of Catania).

While he was deeply rooted in his Sicilian heritage, Frontini was also interested in musical exoticism, frequently imagined as the ideal setting for adventurous love stories. For example, one of his best-known songs is Serenata araba, about which it was written (in 1953, by Domenico Danzuso): “It represents a small jewel of unsurpassable value, and it demonstrates the genius of an artist who, even though he did not know the East, was still able to fully express its spirit, by writing the most beautiful Arabian music”. Another serenade recorded here is equally delightful, though with a very different style: La serenata di Pulcinella (“Punch’s serenade”) wavers between irony and tenderness, employing features genuinely excerpted from the spontaneous musicianship of Southern Italy, while also transforming them into a very refined musical work (through a knowledgeable use of harmony and onomatopoeias).

Similar traits are found also in other of his songs: for example, Canto di carrettiere and Marinaresca focus on particular human and social situations, as well as on special “landscapes” and natural contexts, and while they depict faithfully and effectively the lively scenes they promise, they never lack a touch of human sympathy and feeling.

These characteristics are possibly the most fascinating and frequently found in Frontini’s large output of songs: even when the lyrics are rather simple, and merely suggestive of love stories hinted at, rather than properly narrated, the music gives depth to the texts and it brings to life the human traits of the hidden protagonists.

In this perhaps lies Frontini’s genius, and the true worth of his music: by listening to it, the world he lived in and portrayed in his music comes to life once more, and we are brought, by the notes of his music, in another time and another place, tinged with nostalgia, magic and the enchantment of the unknown.

Album Notes by Chiara Bertoglio

Year 2020 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads