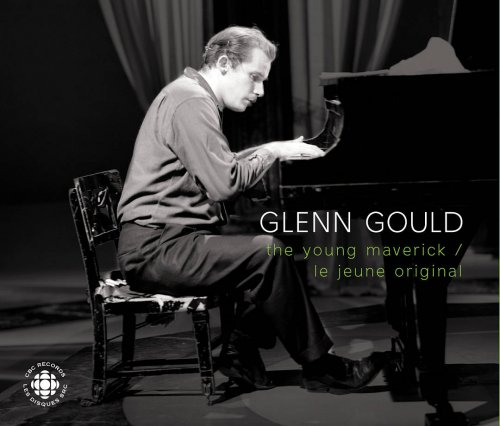

Glenn Gould - The Young Maverick (2007)

BAND/ARTIST: Glenn Gould

- Title: The Young Maverick / Le Jeune Original

- Year Of Release: 2007

- Label: CBC Records

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (image + .cue, log, booklet)

- Total Time: 6:51:05

- Total Size: 1.13 GB

- WebSite: Album Preview

This remarkable set, culled from the archives of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation during the early years in which Glenn Gould emerged as a major classical pianist (1951–55), packages together five discs previously issued singly between 1994 and 1999. The only new CD in the collection is the second Bach disc, which features typically scintillating performances of the Partita No. 5, Three-Part Inventions, Italian Concerto , and the Concerto in D Minor. Of the various discs here, the only one to contain works not issued commercially by Columbia-CBS-Sony is the second Beethoven CD (originally released in 1997 as CBC 2013). Only the op. 126 Bagatelles were recorded later by Gould. Of special interest are the Piano Sonata No. 28 and the “Ghost” Trio with violinist Alexander Schneider and cellist Zara Nelsova. It was partly as a result of this concert that Schneider, under contract to Columbia as the lead violinist of the legendary Budapest String Quartet, told Goddard Lieberson about this young phenomenon, which led to Gould’s exclusive contract signing with the label the following year.

Listening to seven hours (!) of Gould playing is a bit of an overload. This was a pianist who completely submerged himself in his work or, more accurately, merged his own personality with that of the composers he performed. His vision was a shifting one, and his constant emphasis on the skeletal structure of a composition—sort of a hyper-Artur Schnabel approach—made tremendous demands on the listener in terms of detail. He used little or no sustain pedal, yet for the most part was able to create a singing tone. His one failure in this respect, in my view a serious one, was in his playing of the atonal composers. His Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern have no flow, no lyricism, no line. It is all stark, ugly, and off-putting, at least to me, though to be fair I don’t much like these works to begin with, so my views may not be yours.

Little differences abound between these radio broadcasts and the studio recordings that followed, sometimes by more than a decade. Typically, Gould was more scintillating, more impetuous, less reflective in live performance than in studio settings, and it shows. Andantes are generally quicker here than in their studio counterparts, whereas allegros and prestos are about the same, though little touches which he added later, or sometimes removed, add piquant interest. Good examples of what I mean are in the Sinfonias or Three-Part Inventions. No. 2 is much slower and more reflective in the commercial recording. No. 5, same thing, but the CBC broadcast actually sounds too glib. No. 14 is more exciting in the broadcast, also more “regular” in tempo, whereas in the studio recording there is an effective use of rubato, especially towards the end. On the other hand, Sinfonia No. 15 is a quickly moving filigree of sound in the 1964 studio recording, while the radio broadcast reveals a more highly detailed, coruscating reading. In the studio album, Gould interspersed the three-part inventions with the two-part inventions, yet it’s interesting that he kept almost the same order with one exception, Nos. 12 and 13 being reversed in the studio version. Personally, I found his “live” June 1954 performance of the Goldberg Variations, and the October 1952 broadcast of Beethoven’s “Eroica” Variations, far more exciting, and valid, than their celebrated studio counterparts, but you are free to disagree.

Perhaps the one performance that contrasts most strongly with its studio counterpart is the Bach D-Minor Concerto. In this 1955 broadcast, MacMillan leads a fairly large sized orchestra playing with what we now recognize as “Romantic” rather than Baroque accents, though Gould’s performance, surprisingly, is introspective and delicately chiseled, especially in the first movement. In the studio recording with Leonard Bernstein, despite slower tempos and an equally full-sized orchestra, Gould sprinkles the line liberally with little dramatic accents, and Bernstein phrases the music more appropriately for its period (though certainly not as sharply as we hear it today). As a result, I found the broadcast an interesting curio, but not particularly gripping in accent or phrasing, and unable to sustain as much interest.

I shall not give detailed comparisons of the first three Beethoven concertos to his studio recordings, all with the “Columbia Symphony Orchestra” (the first conducted by Vladimir Golschmann, the second and third by Bernstein), except that I never liked Bernstein’s Beethoven in any circumstances. As auditory experiences, I enjoyed these performances tremendously. MacMillan, who truly was a fine conductor, is more at home in Beethoven than in Bach, and his support for the soloist is remarkable for its combined drama and suppleness. The Toronto Symphony plays extremely well. Comparisons with Schnabel are particularly apt in this music, especially the slow movements, which are more sustained and singing than with Bernstein (Bernstein’s conducting of the Second Concerto is particularly brutal). Here, at least in the first two concertos, Gould indeed uses the sustain pedal, and quite effectively, to create mood. The only difference between the last movement of the Second Concerto and the stand-alone last movement performed eight months earlier is the boxier studio sound and the less incisive conducting of Paul Scherman. Heinz Unger, apparently a fan of Toscanini’s quick tempos, couldn’t sustain a legato flow as well as either Toscanini or MacMillan. Nevertheless, Gould is superb here, Unger is still better than Bernstein, and the dynamic range of this recording (made February 21, 1955) is much more vivid than the earlier Beethoven broadcasts with MacMillan.

Oddly enough, the accompanying booklet does not give the performance dates of the first two Beethoven concertos or the 12-tone works. For those who choose to acquire this set, and not the individual discs, they are as follows. Beethoven Concerto No. 1, January 23, 1951; Concerto No. 2, December 12, 1951; the stand-alone last movement of the Second Concerto, April 1, 1951. The Schoenberg Concerto was broadcast December 21, 1953; the Webern Piano Variations were given January 9, 1954; the others come from the concert of October 14, 1952.

The CBC, apparently, was still using acetate discs to record their radio programs at a time when both NBC and BBC were using magnetic tape. As a result, there is less frequency range in these discs than in contemporary NBC and BBC broadcasts, as well as occasional “disc swish.” The CBC has cleaned up the sound somewhat, but certain sides (i.e., the slow movement of the Italian Concerto) remain particularly noisy in the background. Gould’s crystal tone is captured with decently realistic sound. But what really makes this entire set so treasurable is to hear Gould happily making music in the confines of a radio studio, live and in person (though usually not with an audience after 1951). I never quite understood why CBS didn’t take advantage of its network facilities to offer U.S. viewers Gould concerts, on radio or television, during the 1960s. Your proclivity to obtain this set will, of course, depend on how well you respond to Gould’s slight eccentricities of interpretation, which here were still in an embryonic and relatively traditional state. As George Szell said when he resigned from performing Beethoven’s “Emperor” Concerto with Gould, “That man is a nut!” But then, when he heard the performance (with Stokowski conducting), he made his even more famous remark: “That nut is a genius!” Listeners have been alternately thrilled, angered, laudatory, and dismissive of Gould for nearly 60 years. Come on, buy this set and join the club. ~ FANFARE: Lynn René Bayley

Listening to seven hours (!) of Gould playing is a bit of an overload. This was a pianist who completely submerged himself in his work or, more accurately, merged his own personality with that of the composers he performed. His vision was a shifting one, and his constant emphasis on the skeletal structure of a composition—sort of a hyper-Artur Schnabel approach—made tremendous demands on the listener in terms of detail. He used little or no sustain pedal, yet for the most part was able to create a singing tone. His one failure in this respect, in my view a serious one, was in his playing of the atonal composers. His Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern have no flow, no lyricism, no line. It is all stark, ugly, and off-putting, at least to me, though to be fair I don’t much like these works to begin with, so my views may not be yours.

Little differences abound between these radio broadcasts and the studio recordings that followed, sometimes by more than a decade. Typically, Gould was more scintillating, more impetuous, less reflective in live performance than in studio settings, and it shows. Andantes are generally quicker here than in their studio counterparts, whereas allegros and prestos are about the same, though little touches which he added later, or sometimes removed, add piquant interest. Good examples of what I mean are in the Sinfonias or Three-Part Inventions. No. 2 is much slower and more reflective in the commercial recording. No. 5, same thing, but the CBC broadcast actually sounds too glib. No. 14 is more exciting in the broadcast, also more “regular” in tempo, whereas in the studio recording there is an effective use of rubato, especially towards the end. On the other hand, Sinfonia No. 15 is a quickly moving filigree of sound in the 1964 studio recording, while the radio broadcast reveals a more highly detailed, coruscating reading. In the studio album, Gould interspersed the three-part inventions with the two-part inventions, yet it’s interesting that he kept almost the same order with one exception, Nos. 12 and 13 being reversed in the studio version. Personally, I found his “live” June 1954 performance of the Goldberg Variations, and the October 1952 broadcast of Beethoven’s “Eroica” Variations, far more exciting, and valid, than their celebrated studio counterparts, but you are free to disagree.

Perhaps the one performance that contrasts most strongly with its studio counterpart is the Bach D-Minor Concerto. In this 1955 broadcast, MacMillan leads a fairly large sized orchestra playing with what we now recognize as “Romantic” rather than Baroque accents, though Gould’s performance, surprisingly, is introspective and delicately chiseled, especially in the first movement. In the studio recording with Leonard Bernstein, despite slower tempos and an equally full-sized orchestra, Gould sprinkles the line liberally with little dramatic accents, and Bernstein phrases the music more appropriately for its period (though certainly not as sharply as we hear it today). As a result, I found the broadcast an interesting curio, but not particularly gripping in accent or phrasing, and unable to sustain as much interest.

I shall not give detailed comparisons of the first three Beethoven concertos to his studio recordings, all with the “Columbia Symphony Orchestra” (the first conducted by Vladimir Golschmann, the second and third by Bernstein), except that I never liked Bernstein’s Beethoven in any circumstances. As auditory experiences, I enjoyed these performances tremendously. MacMillan, who truly was a fine conductor, is more at home in Beethoven than in Bach, and his support for the soloist is remarkable for its combined drama and suppleness. The Toronto Symphony plays extremely well. Comparisons with Schnabel are particularly apt in this music, especially the slow movements, which are more sustained and singing than with Bernstein (Bernstein’s conducting of the Second Concerto is particularly brutal). Here, at least in the first two concertos, Gould indeed uses the sustain pedal, and quite effectively, to create mood. The only difference between the last movement of the Second Concerto and the stand-alone last movement performed eight months earlier is the boxier studio sound and the less incisive conducting of Paul Scherman. Heinz Unger, apparently a fan of Toscanini’s quick tempos, couldn’t sustain a legato flow as well as either Toscanini or MacMillan. Nevertheless, Gould is superb here, Unger is still better than Bernstein, and the dynamic range of this recording (made February 21, 1955) is much more vivid than the earlier Beethoven broadcasts with MacMillan.

Oddly enough, the accompanying booklet does not give the performance dates of the first two Beethoven concertos or the 12-tone works. For those who choose to acquire this set, and not the individual discs, they are as follows. Beethoven Concerto No. 1, January 23, 1951; Concerto No. 2, December 12, 1951; the stand-alone last movement of the Second Concerto, April 1, 1951. The Schoenberg Concerto was broadcast December 21, 1953; the Webern Piano Variations were given January 9, 1954; the others come from the concert of October 14, 1952.

The CBC, apparently, was still using acetate discs to record their radio programs at a time when both NBC and BBC were using magnetic tape. As a result, there is less frequency range in these discs than in contemporary NBC and BBC broadcasts, as well as occasional “disc swish.” The CBC has cleaned up the sound somewhat, but certain sides (i.e., the slow movement of the Italian Concerto) remain particularly noisy in the background. Gould’s crystal tone is captured with decently realistic sound. But what really makes this entire set so treasurable is to hear Gould happily making music in the confines of a radio studio, live and in person (though usually not with an audience after 1951). I never quite understood why CBS didn’t take advantage of its network facilities to offer U.S. viewers Gould concerts, on radio or television, during the 1960s. Your proclivity to obtain this set will, of course, depend on how well you respond to Gould’s slight eccentricities of interpretation, which here were still in an embryonic and relatively traditional state. As George Szell said when he resigned from performing Beethoven’s “Emperor” Concerto with Gould, “That man is a nut!” But then, when he heard the performance (with Stokowski conducting), he made his even more famous remark: “That nut is a genius!” Listeners have been alternately thrilled, angered, laudatory, and dismissive of Gould for nearly 60 years. Come on, buy this set and join the club. ~ FANFARE: Lynn René Bayley

Related Release:

Classical | FLAC / APE | CD-Rip

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads