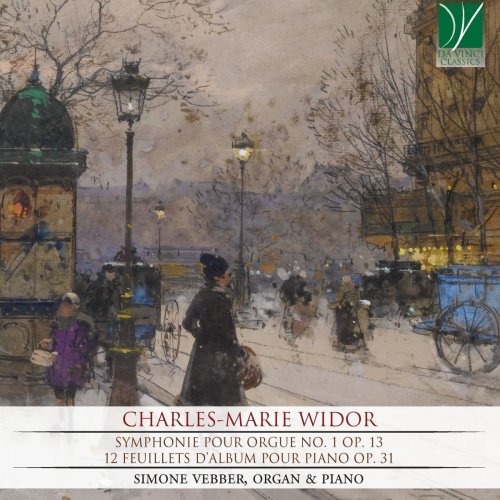

Simone Vebber - Charles-Marie Widor - Symphonie pour orgue No. 1 Op. 13 - 12 Feuillets d'album pour piano Op. 31 (2019)

BAND/ARTIST: Simone Vebber

- Title: Charles-Marie Widor - Symphonie pour orgue No. 1 Op. 13 - 12 Feuillets d'album pour piano Op. 31

- Year Of Release: 2019

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 64:10 min

- Total Size: 249 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

01. Organ Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 13 No.1: I. Prélude

02. Organ Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 13 No.1: II. Allegretto

03. Organ Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 13 No.1: III. Adagio

04. Organ Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 13 No.1: IV. Intermezzo

05. Organ Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 13 No.1: V. Marche Pontificale

06. Organ Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 13 No.1: VI. Méditation

07. Organ Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 13 No.1: VII. Finale

08. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 1, Op. 31: No. 1, Lilas

09. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 1, Op. 31: No. 2, Papillons bleus

10. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 1, Op. 31: No. 3, Chanson matinale

11. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 1, Op. 31: No. 4, Drame

12. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 1, Op. 31: No. 5, Nuit sereine

13. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 1, Op. 31: No. 6, Valse lente

14. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 2, Op. 31: No. 1, Solitude

15. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 2, Op. 31: No. 2, Bruits d'aîles

16. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 2, Op. 31: No. 3, Pensée

17. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 2, Op. 31: No. 4, Ciel gris

18. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 2, Op. 31: No. 5, Marche américaine

19. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 2, Op. 31: No. 6, Myosotis

01. Organ Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 13 No.1: I. Prélude

02. Organ Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 13 No.1: II. Allegretto

03. Organ Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 13 No.1: III. Adagio

04. Organ Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 13 No.1: IV. Intermezzo

05. Organ Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 13 No.1: V. Marche Pontificale

06. Organ Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 13 No.1: VI. Méditation

07. Organ Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 13 No.1: VII. Finale

08. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 1, Op. 31: No. 1, Lilas

09. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 1, Op. 31: No. 2, Papillons bleus

10. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 1, Op. 31: No. 3, Chanson matinale

11. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 1, Op. 31: No. 4, Drame

12. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 1, Op. 31: No. 5, Nuit sereine

13. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 1, Op. 31: No. 6, Valse lente

14. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 2, Op. 31: No. 1, Solitude

15. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 2, Op. 31: No. 2, Bruits d'aîles

16. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 2, Op. 31: No. 3, Pensée

17. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 2, Op. 31: No. 4, Ciel gris

18. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 2, Op. 31: No. 5, Marche américaine

19. 12 Feuillets d'album - Book 2, Op. 31: No. 6, Myosotis

Organists are frequently asked a question by curious listeners and by church-goers who have only a shallow knowledge of music: “What difference is there between a piano and an organ?”. Indeed, the contrary question is much more easily answered: what the piano and the organ do have in common is little more than the sequence of white and black keys. Everything else, including the means by which sound is produced and how it is regulated in volume, timbre and articulation, is entirely and dramatically different.

Therefore, even though many pianists can play the organ and vice-versa, a performer who can master both instruments at a truly professional level is very rarely found. Using one’s ten fingers to press the keys represents just the basics of both instruments. The mark of accomplished pianists is their touch, i.e. their capability to fine-tune the attack of the fingers on the key in order to modify both the intensity and the quality of the sound. To these ends, pianists also make use of the pedals, which can be used, in turn, in various degrees and combinations. On the other hand, the organ’s pedalboard is, to all purposes, one further keyboard on which the organist’s feet play adroitly; a variety of devices – first and foremost the organ’s stops – are employed in order to intervene on the quality and quantity of sound. If pianists frequently complain about the quasi-impossibility of playing on their own instrument in concert halls, and about the consequent necessity of acquainting themselves with new pianos on every occasion, organists need to carefully study each new instrument they need to play, since the differences between two given organs can match those between a Baroque string orchestra on period instruments and a modern symphony orchestra.

Indeed, Charles-Marie Widor (Lyons, 1845 – Paris, 1937) saw the organ precisely in this way: as a full orchestra whose immense variety of sounds was only waiting for a skilled organist to awaken it. Widor came from a family of organists and organ builders, and therefore was deeply acquainted with the secrets of the organ and of organ-making since a very young age. The Widor family numbered, among its friends, Aristide Cavaillé-Coll (1811-1899), one of the greatest organ-builders of all times and the creator of the French Romantic organ – a new variety of instruments with a previously unimaginable power, flexibility, personality. Some of the most imposing organs in the French cathedrals and basilicas were created or improved by him, including that of Notre Dame in Paris (which rather miraculously survived the devastating fire destroying the cathedral’s roof in April 2019).

Cavaillé-Coll acted as a mentor for young Widor, advising him to move to Brussels in order to study with Jaak Lemmens and with François-Joseph Fétis; later, Cavaillé-Coll actively supported Widor and succeeded in obtaining for him, in 1870, an appointment at the church of Saint-Sulpice. That same church was home to one of Cavaillé-Coll’s masterpieces, which had been inaugurated only a few years earlier, in 1862. It was (and still is) a monumental instrument, practically unmatched at the time of its building, and which was furnished with more than a hundred stops and almost seven thousand pipes (among its many features). Widor’s provisional appointment at Saint-Sulpice (where he was initially employed for one year) led him to a six-decades-long job in that church: it can be said, therefore, that the Saint-Sulpice organ was the source of inspiration, the working tool and the ideal setting for all of Widor’s numerous organ compositions.

It was, in short, Widor’s own, and almost always available orchestra. This magnificent instrument stimulated his imagination and suited it perfectly; it provided him with an almost limitless palette of colours, shades and combinations. Significantly, Widor explicitly acknowledged the role of the Cavaillé-Coll organs in the preface to his collected Organ Symphonies, praising enthusiastically the numerous innovations their builder brought to the instrument and stating:

From this result: the possibility of confining an entire division in a sonorous prison – opened or closed at will –, the freedom of mixing timbres, the means of intensifying them or gradually tempering them, the freedom of tempos, the sureness of attacks, the balance of contrasts, and, finally, a whole blossoming of wonderful colours – a rich palette of the most diverse shades: harmonic flutes, gambas, bassoons, English horns, trumpets, celestes, flute stops and reed stops of a quality and variety unknown before. The modern organ is essentially symphonic. The new instrument requires a new language, an ideal other than scholastic polyphony. It is no longer the Bach of the Fugue whom we invoke, but the heard-rending melodist, the pre-eminently expressive master of the Prelude, the Magnificat, the B-minor Mass, the Cantatas, and the St. Matthew Passion. […] Henceforth one will have to exercise the same care with the combination of timbres in an organ composition as in an orchestral work [transl. John R. Near].

Baroque organs, in Widor’s view, had just a “black and white” quality; modern organs had infinite nuances. By reading his words, one perceives clearly the feeling of quasi-intoxication he enjoyed when playing on, and writing for, his great organ. Thus, his Organ Symphonies bear this unusual name not by virtue of their formal structure (particularly the first ones are akin to Suites rather than to Sonata forms), but rather in consideration of their rich, gorgeous and generous instrumentation. Indeed, as Widor himself seemed to state in the same Preface, the organ has the orchestra’s advantages without its limitations: it has a similar variety of sound but without the risk of imprecision (“promiscuity”, in Widor’s words) produced by the high number of performers.

His First Symphony, recorded here (written in 1872 and frequently revised in the following years), seems to thoroughly relish the inebriating resources of Widor’s organ. It comprises seven movements: most of them have a well-defined style (which undergoes developments and modifications but normally remains rather homogeneous within a single movement), and together they seem to compose a rainbow of contrasting colours. The opening Prélude is a majestic piece with evident reminiscences of Baroque features, with its refined counterpoint and its legato/staccato articulation. By contrast, the following Allegro has a more virtuoso and complex structure, in an A-B-A form and in a brisk triple meter. The Intermezzo suggests Mendelssohnian atmospheres; the organ’s gigantic power is bended here to an extreme delicacy, brilliancy and lightness, occasionally interrupted by stormy forte passages, in a whirling perpetuum mobile. The Adagio, instead, is a more intimate and lyrical piece, alluding to the Pastorale style in spite of its complex chromatic wanderings. A still different mood is that of the fifth movement, Marche Pontificale, where the organ displays its fullest sonorities and the solemn grandiosity of its enthralling sound; this is juxtaposed, however, with contrasting sections weaving a complex fabric of styles. Once more, the following Méditation opens an entirely different perspective: this piece, vaguely reminiscent of Bach’s Prelude n. 8 in the Well-Tempered Clavier, vol. I, is a slow and touching piece in a compound metre. The closing Finale is a quick-paced and self-assured allegro whose heavily chromatic subject touches almost all the twelve semitones; its extremely complex harmonic and polyphonic treatment gives way, in the conclusion, to the certainty of a stately C-major chord.

By way of contrast, the 12 Feuillets d’album – a collection of twelve miniature pieces for the piano – display this instrument in one of the social functions it had in the nineteenth century: while the organ was essentially a public instrument, and was almost exclusively played by men, the piano was the favourite domestic instrument, and it was a favourite pastime of the well-educated girls and women. It is indeed to a female friend, Miss Leila Morse, that these delightful short pieces are dedicated; and even though they display, in turn, an ample variety of moods and styles, both their titles and their content are more subdued and more intimate than those found in the massive Organ Symphony. Lilas is a tender Andantino, whose skilful polyphonic writing is almost hidden beneath its deceivingly simple façade. Papillons bleus is a joyful and brilliant piece, whose title and style allude to the eponymous pieces by Robert Schumann. Chanson matinale features an exquisite melody, accompanied by a rocking syncopated rhythm, while Drame is one of the most technically demanding and effective pieces, with bold octave passages and large chords. Nuit sereine is reminiscent of Liszt’s masterful treatment of the arpeggios and of the melodies revealed behind their cascades; Valse lente is a composed, noble and majestic dance, full of nobility and slightly supercilious. In the second volume, Solitude has a delicate feeling of nostalgia over an idiomatic and interesting rhythmical ostinato; Bruits d’ailes is an etude-like piece, evoking fluttering wings and enchanted atmospheres. Pensée displays the expressive value of rubato, here prescribed in detail through the use of continuing and slightly anxious syncopations; Ciel gris is a rather slow and despondent piece, suggesting a feeling of ennui and an almost Baudelairian spleen. Marche américaine, one of the best-known pieces in the series, is another march: by comparing it with Marche pontificale in the Organ Symphony it is possible to observe Widor’s skill in subtly differentiating between the military and excited atmosphere of the piano piece and the religious solemnity of its organistic counterpart. Finally, Myosotis closes the cycle on a note similar to that of the opening piece: two flowers, with their beautiful simplicity and their delicate elegance, encase this refined collection.

On the one hand, then, this CD is one of the most complete and concise demonstrations of “what is the difference between a piano and an organ”; on the other, however, the pairing of the “symphonic organ work” with the “domestic piano cycle” shows the versatility and accomplishment of both the composer and the performer of these complementary and drastically different works.

Album Notes by Chiara Bertoglio

Therefore, even though many pianists can play the organ and vice-versa, a performer who can master both instruments at a truly professional level is very rarely found. Using one’s ten fingers to press the keys represents just the basics of both instruments. The mark of accomplished pianists is their touch, i.e. their capability to fine-tune the attack of the fingers on the key in order to modify both the intensity and the quality of the sound. To these ends, pianists also make use of the pedals, which can be used, in turn, in various degrees and combinations. On the other hand, the organ’s pedalboard is, to all purposes, one further keyboard on which the organist’s feet play adroitly; a variety of devices – first and foremost the organ’s stops – are employed in order to intervene on the quality and quantity of sound. If pianists frequently complain about the quasi-impossibility of playing on their own instrument in concert halls, and about the consequent necessity of acquainting themselves with new pianos on every occasion, organists need to carefully study each new instrument they need to play, since the differences between two given organs can match those between a Baroque string orchestra on period instruments and a modern symphony orchestra.

Indeed, Charles-Marie Widor (Lyons, 1845 – Paris, 1937) saw the organ precisely in this way: as a full orchestra whose immense variety of sounds was only waiting for a skilled organist to awaken it. Widor came from a family of organists and organ builders, and therefore was deeply acquainted with the secrets of the organ and of organ-making since a very young age. The Widor family numbered, among its friends, Aristide Cavaillé-Coll (1811-1899), one of the greatest organ-builders of all times and the creator of the French Romantic organ – a new variety of instruments with a previously unimaginable power, flexibility, personality. Some of the most imposing organs in the French cathedrals and basilicas were created or improved by him, including that of Notre Dame in Paris (which rather miraculously survived the devastating fire destroying the cathedral’s roof in April 2019).

Cavaillé-Coll acted as a mentor for young Widor, advising him to move to Brussels in order to study with Jaak Lemmens and with François-Joseph Fétis; later, Cavaillé-Coll actively supported Widor and succeeded in obtaining for him, in 1870, an appointment at the church of Saint-Sulpice. That same church was home to one of Cavaillé-Coll’s masterpieces, which had been inaugurated only a few years earlier, in 1862. It was (and still is) a monumental instrument, practically unmatched at the time of its building, and which was furnished with more than a hundred stops and almost seven thousand pipes (among its many features). Widor’s provisional appointment at Saint-Sulpice (where he was initially employed for one year) led him to a six-decades-long job in that church: it can be said, therefore, that the Saint-Sulpice organ was the source of inspiration, the working tool and the ideal setting for all of Widor’s numerous organ compositions.

It was, in short, Widor’s own, and almost always available orchestra. This magnificent instrument stimulated his imagination and suited it perfectly; it provided him with an almost limitless palette of colours, shades and combinations. Significantly, Widor explicitly acknowledged the role of the Cavaillé-Coll organs in the preface to his collected Organ Symphonies, praising enthusiastically the numerous innovations their builder brought to the instrument and stating:

From this result: the possibility of confining an entire division in a sonorous prison – opened or closed at will –, the freedom of mixing timbres, the means of intensifying them or gradually tempering them, the freedom of tempos, the sureness of attacks, the balance of contrasts, and, finally, a whole blossoming of wonderful colours – a rich palette of the most diverse shades: harmonic flutes, gambas, bassoons, English horns, trumpets, celestes, flute stops and reed stops of a quality and variety unknown before. The modern organ is essentially symphonic. The new instrument requires a new language, an ideal other than scholastic polyphony. It is no longer the Bach of the Fugue whom we invoke, but the heard-rending melodist, the pre-eminently expressive master of the Prelude, the Magnificat, the B-minor Mass, the Cantatas, and the St. Matthew Passion. […] Henceforth one will have to exercise the same care with the combination of timbres in an organ composition as in an orchestral work [transl. John R. Near].

Baroque organs, in Widor’s view, had just a “black and white” quality; modern organs had infinite nuances. By reading his words, one perceives clearly the feeling of quasi-intoxication he enjoyed when playing on, and writing for, his great organ. Thus, his Organ Symphonies bear this unusual name not by virtue of their formal structure (particularly the first ones are akin to Suites rather than to Sonata forms), but rather in consideration of their rich, gorgeous and generous instrumentation. Indeed, as Widor himself seemed to state in the same Preface, the organ has the orchestra’s advantages without its limitations: it has a similar variety of sound but without the risk of imprecision (“promiscuity”, in Widor’s words) produced by the high number of performers.

His First Symphony, recorded here (written in 1872 and frequently revised in the following years), seems to thoroughly relish the inebriating resources of Widor’s organ. It comprises seven movements: most of them have a well-defined style (which undergoes developments and modifications but normally remains rather homogeneous within a single movement), and together they seem to compose a rainbow of contrasting colours. The opening Prélude is a majestic piece with evident reminiscences of Baroque features, with its refined counterpoint and its legato/staccato articulation. By contrast, the following Allegro has a more virtuoso and complex structure, in an A-B-A form and in a brisk triple meter. The Intermezzo suggests Mendelssohnian atmospheres; the organ’s gigantic power is bended here to an extreme delicacy, brilliancy and lightness, occasionally interrupted by stormy forte passages, in a whirling perpetuum mobile. The Adagio, instead, is a more intimate and lyrical piece, alluding to the Pastorale style in spite of its complex chromatic wanderings. A still different mood is that of the fifth movement, Marche Pontificale, where the organ displays its fullest sonorities and the solemn grandiosity of its enthralling sound; this is juxtaposed, however, with contrasting sections weaving a complex fabric of styles. Once more, the following Méditation opens an entirely different perspective: this piece, vaguely reminiscent of Bach’s Prelude n. 8 in the Well-Tempered Clavier, vol. I, is a slow and touching piece in a compound metre. The closing Finale is a quick-paced and self-assured allegro whose heavily chromatic subject touches almost all the twelve semitones; its extremely complex harmonic and polyphonic treatment gives way, in the conclusion, to the certainty of a stately C-major chord.

By way of contrast, the 12 Feuillets d’album – a collection of twelve miniature pieces for the piano – display this instrument in one of the social functions it had in the nineteenth century: while the organ was essentially a public instrument, and was almost exclusively played by men, the piano was the favourite domestic instrument, and it was a favourite pastime of the well-educated girls and women. It is indeed to a female friend, Miss Leila Morse, that these delightful short pieces are dedicated; and even though they display, in turn, an ample variety of moods and styles, both their titles and their content are more subdued and more intimate than those found in the massive Organ Symphony. Lilas is a tender Andantino, whose skilful polyphonic writing is almost hidden beneath its deceivingly simple façade. Papillons bleus is a joyful and brilliant piece, whose title and style allude to the eponymous pieces by Robert Schumann. Chanson matinale features an exquisite melody, accompanied by a rocking syncopated rhythm, while Drame is one of the most technically demanding and effective pieces, with bold octave passages and large chords. Nuit sereine is reminiscent of Liszt’s masterful treatment of the arpeggios and of the melodies revealed behind their cascades; Valse lente is a composed, noble and majestic dance, full of nobility and slightly supercilious. In the second volume, Solitude has a delicate feeling of nostalgia over an idiomatic and interesting rhythmical ostinato; Bruits d’ailes is an etude-like piece, evoking fluttering wings and enchanted atmospheres. Pensée displays the expressive value of rubato, here prescribed in detail through the use of continuing and slightly anxious syncopations; Ciel gris is a rather slow and despondent piece, suggesting a feeling of ennui and an almost Baudelairian spleen. Marche américaine, one of the best-known pieces in the series, is another march: by comparing it with Marche pontificale in the Organ Symphony it is possible to observe Widor’s skill in subtly differentiating between the military and excited atmosphere of the piano piece and the religious solemnity of its organistic counterpart. Finally, Myosotis closes the cycle on a note similar to that of the opening piece: two flowers, with their beautiful simplicity and their delicate elegance, encase this refined collection.

On the one hand, then, this CD is one of the most complete and concise demonstrations of “what is the difference between a piano and an organ”; on the other, however, the pairing of the “symphonic organ work” with the “domestic piano cycle” shows the versatility and accomplishment of both the composer and the performer of these complementary and drastically different works.

Album Notes by Chiara Bertoglio

Year 2019 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads