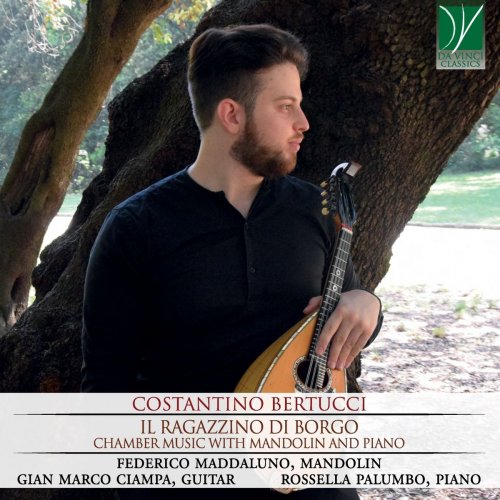

Federico Maddaluno - Costantino Bertucci: Il ragazzino di Borgo (Chamber music with mandolin and piano) (2019)

BAND/ARTIST: Federico Maddaluno

- Title: Costantino Bertucci: Il ragazzino di Borgo (Chamber music with mandolin and piano)

- Year Of Release: 2019

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 50:05 min

- Total Size: 215 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

01. Notturno

02. Ballata

03. Marcia funebre di Pulcinella

04. Falso amore

05. Barcarola

06. Nella foresta

07. Fantasia da Il Trovatore di Verdi

08. Romanza

09. Danza del Diavolo

10. Serenata

11. Les premiers jours des petits enfants

12. Berceuse

13. La luna ci sorprende

14. Fiori nuziali

15. C'era na giardiniera

01. Notturno

02. Ballata

03. Marcia funebre di Pulcinella

04. Falso amore

05. Barcarola

06. Nella foresta

07. Fantasia da Il Trovatore di Verdi

08. Romanza

09. Danza del Diavolo

10. Serenata

11. Les premiers jours des petits enfants

12. Berceuse

13. La luna ci sorprende

14. Fiori nuziali

15. C'era na giardiniera

Don Giovanni, the protagonist of Mozart’s eponymous opera, is – to use an understatement – very attracted by feminine beauty. A nobleman, he counts (quite literally, as in the famous catalogue aria) many gentlewomen among his conquests; however, his tastes are very democratic, and he does not disdain to offer his love to female members of the lower classes. This happens in the second act of the opera, when Don Giovanni, disguised as his servant Leporello, sings a delightful serenade to the maid of one of his lovers, Donna Elvira. The serenade’s words are passionate and dramatic, with even a passing mention of the death to which the girl’s refusal could allegedly lead Don Giovanni; however, Mozart chooses to clothe these lyrics with a gentle and slightly ironic music. Don Giovanni’s tune is accompanied – both in the theatrical fiction of the stage and in actual sound of the performed music – by the light, elegant and mellow pizzicato sounds of a mandolin. This is perhaps the best-known appearance of the mandolin in the “classical” repertoire, along with the masterpieces composed by Antonio Vivaldi for this instrument.

In spite of this prestigious pedigree and – most importantly – of its enchanting sound and of the aesthetically beautiful shape it inherited from its ancestors (most notably the lute and later the mandola), the mandolin can justly claim to have been somewhat neglected by the “classical” composers, who frequently failed to exploit its timbral and expressive resources. Indeed, the mandolin continues to be a very common instrument, particularly in certain zones of Italy, until present-day: in particular, it is played by cohorts of amateur and by many professional musicians, who frequently constitute entire orchestras of mandolins; however, their repertoire and their field of action are in most cases confined to what we would call “popular” or “folk” music, gaining no admission on the “classical” concert stage.

If the world of “classical” music seems to be unjustly indifferent to the mandolin, the mandolin has frequently looked to the styles and repertoires of the “cultivated” scene; in particular, the borrowing of pieces and traits from the classical tradition has been encouraged by the fact that the violin and the mandolin share the same tuning, and thus the transcriptions from one instrument to the other are as easy to realize as fascinating to hear.

One of the masters who helped establishing this fundamental connection between the mandolin and the violin was Costantino Bertucci (1841-1931), a Roman musician whose life is almost a symbol of the role he had in the history of his instrument. Just as Bertucci earned fame and success as a “folk” musician and later completed his education with a classical training, so his work was crucial for establishing and affirming the theoretical and methodological framework for the teaching of the mandolin, and in pointing out his instrument’s potential as a solo instrument in the classical tradition.

Bertucci was the son of a gardener who moonlighted as a mandolin and lute virtuoso, and who gave him his first lessons of music when the child was only five. The boy’s precocity was soon evident, however: a mere three years later, father and son were playing together in public. In the following years, Costantino continued his musical training, making an acclaimed debut at the fashionable “Caffè Nuovo” in Rome at twelve; however, similar to his father, he could not, at first, devote himself entirely to music, which was too uncertain a source of income. Notwithstanding this, he quickly achieved local fame, under the nickname of “il ragazzino di Borgo”, “the Borgo boy”.

A fresh impulse to Bertucci’s studies and to his dedication to music came from the teaching and encouragement of Francesco Finestauri, who had been taught in turn by Cesare Galanti, a fine musician who was a director of the Papal Chapel. Bertucci began to complement his performances with a teaching activity of his own, until an event happened which would eventually change the course of his life. As the musician himself recounted it, “On a certain fete, when playing at a garden party, there was present listening to us, a member of the band of the Papal Dragoons, a clarionetist and concert artist in the theatre. He requested me to play certain excerpts from operas, which I did, and in our conversation, I was compelled to acknowledge that I could not read music, for, like most young Italians of that period, I depended upon a good ear and memory. This musician, whose name was Baccani, proved a good friend to me; he became my teacher, and to him I owe much, for by his teaching a new era dawned, and I made great progress”.

Baccani’s teaching helped Bertucci to establish his musicianship on the solid ground of theoretical knowledge; at the same time, Bertucci’s own teaching provided him with important contacts which eventually opened up for him the doors of the high society of the newborn Italian kingdom. Thanks to one of his pupils, Marquise Gavaggi, Bertucci was invited to play at court, where he obtained considerable success. Meanwhile, the mandolin orchestra created by Bertucci had been invited to play in Paris, at the prestigious Trocadéro, thanks to the good offices of another of Bertucci’s former students. Back in Italy, Queen Margherita (who in turn was an amateur mandolin player) asked the orchestra to play for the royal court in Monza, and later invited them to perform at a royal wedding party in 1885. The Queen’s favour continued in the following years, as she actively promoted Bertucci’s orchestra and the mandolin in general.

This positive ambiance encouraged Bertucci to devote himself to the improvement of the instrument and of its repertoire: he contributed to the mandolin’s building technique with some important enhancements, and he endowed his instrument with a rich repertoire and with treatises, methods and etude collections. Indeed, if Don Giovanni’s serenade is one of the most famous appearances of the mandolin on the operatic stage, the operatic world was a continuous source of inspiration for Bertucci and for his contemporaries. A particularly brilliant example of this influence is found in the great Fantasia sul Trovatore di G. Verdi found in this Da Vinci Classics CD: the themes and the characters of Verdi’s opera are skillfully intertwined in a fashion which demonstrates both Bertucci’s familiarity with the contemporaneous musical idiom and his own personal inventiveness.

Among the other works on this CD, La marcia funebre di Pulcinella (“Punch’s funeral march”) is an ironic and yet somewhat touching piece which seems to build an ideal bridge between Bertucci’s Rome and Charles Gounod’s Paris: the Marche funèbre d’une marionnette written by the French composer in 1872 similarly walks on the border between melancholy and humour. A genuine romance, in a rhapsodic mood, characterizes instead the Notturno and the Ballata, whose touching traits are echoed also in the Berceuse (with piano accompaniment) found in this CD.

Love, in all of its expressions, is the driving force behind many other pieces performed here: in Falso amore (“False love”), the broken musical phrases and audacious harmonic sequences express the pains of a despised lover; the passionate dynamics of courtship are evoked in Romanza, where a warm tune – played in the characteristic mandolin tremolo – is sustained by a gentle accompaniment which betrays the not-too-serious traits of this otherwise fervent plea. A similar – though perhaps more earnest atmosphere – is also found in Serenata, where the duet between mandolin and guitar seems to echo the dialogue of the two lovers. Also in La luna ci sorprende (“The moon surprises us”), with a piano accompaniment in the style of a barcarolle, the mandolin gives voice to the palpitating singing of a serenade by moonlight.

The joy of reciprocal love shows itself in the cheerful and radiant tenderness of Fiori nuziali (“Nuptial flowers”), again with piano, while the solo piece Nella foresta (“In the forest”) seems to embody, in the symbol of the woods, the fascination of the unknown which characterizes the experience of loving and being loved. In Les Premiers, the piano’s introduction demonstrates Bertucci’s mastery of the contemporaneous language of classical music; the mandolin enters gradually, with a powerful expressive effect which enhances the emotional impact of the piece. C’era una giardiniera (“There was a gardeneress”) is almost a concerto for the mandolin, due to its extended size, contrasted sections, and careful balance of touching and brilliant moments. It may also contain a veiled – and yet moving – allusion to Bertucci’s own life, since his father – as will be recalled – had been a gardener. Sheer virtuosity, of an almost Paganini-like style, is demanded also by the Danza del diavolo (“Devil’s dance”), which once more establishes a meaningful connection between the mandolin and the violin.

In their diversity and variety, all of these pieces bear witness to Bertucci’s fantasy, creativity, and to the legacy he left to his instrument, its repertoire and its playing and building technique. It is to be hoped that, just as Bertucci helped to bridge the gap between folk and classical music of his time, so this CD will encourage a renewed attention for this instrument and repertoire on today’s classical stage.

Album Notes by Chiara Bertoglio

In spite of this prestigious pedigree and – most importantly – of its enchanting sound and of the aesthetically beautiful shape it inherited from its ancestors (most notably the lute and later the mandola), the mandolin can justly claim to have been somewhat neglected by the “classical” composers, who frequently failed to exploit its timbral and expressive resources. Indeed, the mandolin continues to be a very common instrument, particularly in certain zones of Italy, until present-day: in particular, it is played by cohorts of amateur and by many professional musicians, who frequently constitute entire orchestras of mandolins; however, their repertoire and their field of action are in most cases confined to what we would call “popular” or “folk” music, gaining no admission on the “classical” concert stage.

If the world of “classical” music seems to be unjustly indifferent to the mandolin, the mandolin has frequently looked to the styles and repertoires of the “cultivated” scene; in particular, the borrowing of pieces and traits from the classical tradition has been encouraged by the fact that the violin and the mandolin share the same tuning, and thus the transcriptions from one instrument to the other are as easy to realize as fascinating to hear.

One of the masters who helped establishing this fundamental connection between the mandolin and the violin was Costantino Bertucci (1841-1931), a Roman musician whose life is almost a symbol of the role he had in the history of his instrument. Just as Bertucci earned fame and success as a “folk” musician and later completed his education with a classical training, so his work was crucial for establishing and affirming the theoretical and methodological framework for the teaching of the mandolin, and in pointing out his instrument’s potential as a solo instrument in the classical tradition.

Bertucci was the son of a gardener who moonlighted as a mandolin and lute virtuoso, and who gave him his first lessons of music when the child was only five. The boy’s precocity was soon evident, however: a mere three years later, father and son were playing together in public. In the following years, Costantino continued his musical training, making an acclaimed debut at the fashionable “Caffè Nuovo” in Rome at twelve; however, similar to his father, he could not, at first, devote himself entirely to music, which was too uncertain a source of income. Notwithstanding this, he quickly achieved local fame, under the nickname of “il ragazzino di Borgo”, “the Borgo boy”.

A fresh impulse to Bertucci’s studies and to his dedication to music came from the teaching and encouragement of Francesco Finestauri, who had been taught in turn by Cesare Galanti, a fine musician who was a director of the Papal Chapel. Bertucci began to complement his performances with a teaching activity of his own, until an event happened which would eventually change the course of his life. As the musician himself recounted it, “On a certain fete, when playing at a garden party, there was present listening to us, a member of the band of the Papal Dragoons, a clarionetist and concert artist in the theatre. He requested me to play certain excerpts from operas, which I did, and in our conversation, I was compelled to acknowledge that I could not read music, for, like most young Italians of that period, I depended upon a good ear and memory. This musician, whose name was Baccani, proved a good friend to me; he became my teacher, and to him I owe much, for by his teaching a new era dawned, and I made great progress”.

Baccani’s teaching helped Bertucci to establish his musicianship on the solid ground of theoretical knowledge; at the same time, Bertucci’s own teaching provided him with important contacts which eventually opened up for him the doors of the high society of the newborn Italian kingdom. Thanks to one of his pupils, Marquise Gavaggi, Bertucci was invited to play at court, where he obtained considerable success. Meanwhile, the mandolin orchestra created by Bertucci had been invited to play in Paris, at the prestigious Trocadéro, thanks to the good offices of another of Bertucci’s former students. Back in Italy, Queen Margherita (who in turn was an amateur mandolin player) asked the orchestra to play for the royal court in Monza, and later invited them to perform at a royal wedding party in 1885. The Queen’s favour continued in the following years, as she actively promoted Bertucci’s orchestra and the mandolin in general.

This positive ambiance encouraged Bertucci to devote himself to the improvement of the instrument and of its repertoire: he contributed to the mandolin’s building technique with some important enhancements, and he endowed his instrument with a rich repertoire and with treatises, methods and etude collections. Indeed, if Don Giovanni’s serenade is one of the most famous appearances of the mandolin on the operatic stage, the operatic world was a continuous source of inspiration for Bertucci and for his contemporaries. A particularly brilliant example of this influence is found in the great Fantasia sul Trovatore di G. Verdi found in this Da Vinci Classics CD: the themes and the characters of Verdi’s opera are skillfully intertwined in a fashion which demonstrates both Bertucci’s familiarity with the contemporaneous musical idiom and his own personal inventiveness.

Among the other works on this CD, La marcia funebre di Pulcinella (“Punch’s funeral march”) is an ironic and yet somewhat touching piece which seems to build an ideal bridge between Bertucci’s Rome and Charles Gounod’s Paris: the Marche funèbre d’une marionnette written by the French composer in 1872 similarly walks on the border between melancholy and humour. A genuine romance, in a rhapsodic mood, characterizes instead the Notturno and the Ballata, whose touching traits are echoed also in the Berceuse (with piano accompaniment) found in this CD.

Love, in all of its expressions, is the driving force behind many other pieces performed here: in Falso amore (“False love”), the broken musical phrases and audacious harmonic sequences express the pains of a despised lover; the passionate dynamics of courtship are evoked in Romanza, where a warm tune – played in the characteristic mandolin tremolo – is sustained by a gentle accompaniment which betrays the not-too-serious traits of this otherwise fervent plea. A similar – though perhaps more earnest atmosphere – is also found in Serenata, where the duet between mandolin and guitar seems to echo the dialogue of the two lovers. Also in La luna ci sorprende (“The moon surprises us”), with a piano accompaniment in the style of a barcarolle, the mandolin gives voice to the palpitating singing of a serenade by moonlight.

The joy of reciprocal love shows itself in the cheerful and radiant tenderness of Fiori nuziali (“Nuptial flowers”), again with piano, while the solo piece Nella foresta (“In the forest”) seems to embody, in the symbol of the woods, the fascination of the unknown which characterizes the experience of loving and being loved. In Les Premiers, the piano’s introduction demonstrates Bertucci’s mastery of the contemporaneous language of classical music; the mandolin enters gradually, with a powerful expressive effect which enhances the emotional impact of the piece. C’era una giardiniera (“There was a gardeneress”) is almost a concerto for the mandolin, due to its extended size, contrasted sections, and careful balance of touching and brilliant moments. It may also contain a veiled – and yet moving – allusion to Bertucci’s own life, since his father – as will be recalled – had been a gardener. Sheer virtuosity, of an almost Paganini-like style, is demanded also by the Danza del diavolo (“Devil’s dance”), which once more establishes a meaningful connection between the mandolin and the violin.

In their diversity and variety, all of these pieces bear witness to Bertucci’s fantasy, creativity, and to the legacy he left to his instrument, its repertoire and its playing and building technique. It is to be hoped that, just as Bertucci helped to bridge the gap between folk and classical music of his time, so this CD will encourage a renewed attention for this instrument and repertoire on today’s classical stage.

Album Notes by Chiara Bertoglio

Year 2019 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads