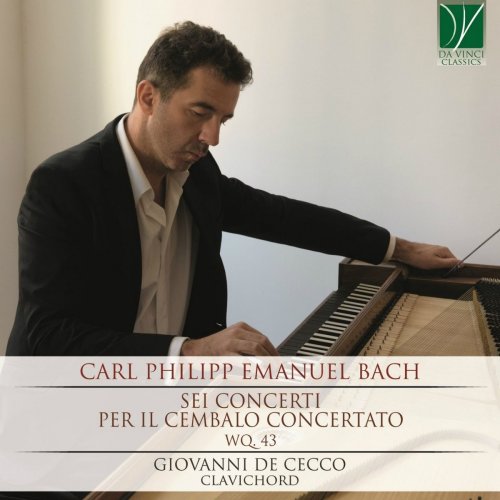

Giovanni De Cecco - Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: Sei concerti per il cembalo concertato (Arr. for Clavichord) (2019)

BAND/ARTIST: Giovanni De Cecco

- Title: Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: Sei concerti per il cembalo concertato (Arr. for Clavichord)

- Year Of Release: 2019

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 123:13 min

- Total Size: 712 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

01. Harpsichord Concerto in F Major, Wq. 43/1: I. Allegro di molto

02. Harpsichord Concerto in F Major, Wq. 43/1: II. Andante

03. Harpsichord Concerto in F Major, Wq. 43/1: III. Prestissimo

04. Harpsichord Concerto in D Major, Wq. 43/2: I. Allegro di molto - Andante - Allegro di molto

05. Harpsichord Concerto in D Major, Wq. 43/2: II. Andante

06. Harpsichord Concerto in D Major, Wq. 43/2: III. Allegretto

07. Harpsichord Concerto in E-Flat Major, Wq. 43/3: I. Allegro

08. Harpsichord Concerto in E-Flat Major, Wq. 43/3: II. Larghetto

09. Harpsichord Concerto in E-Flat Major, Wq. 43/3: III. Presto

10. Harpsichord Concerto in C Minor, Wq. 43/4: I. Allegro assai

11. Harpsichord Concerto in C Minor, Wq. 43/4: II. Poco adagio

12. Harpsichord Concerto in C Minor, Wq. 43/4: III. Tempo di minuetto

13. Harpsichord Concerto in C Minor, Wq. 43/4: IV. Allegro assai

14. Harpsichord Concerto in G Major, Wq. 43/5: I. Adagio - Presto

15. Harpsichord Concerto in G Major, Wq. 43/5: II. Adagio

16. Harpsichord Concerto in G Major, Wq. 43/5: III. Allegro

17. Harpsichord Concerto in C Major, Wq. 43/6: I. Allegro di molto

18. Harpsichord Concerto in C Major, Wq. 43/6: II. Larghetto

19. Harpsichord Concerto in C Major, Wq. 43/6: III. Allegro

01. Harpsichord Concerto in F Major, Wq. 43/1: I. Allegro di molto

02. Harpsichord Concerto in F Major, Wq. 43/1: II. Andante

03. Harpsichord Concerto in F Major, Wq. 43/1: III. Prestissimo

04. Harpsichord Concerto in D Major, Wq. 43/2: I. Allegro di molto - Andante - Allegro di molto

05. Harpsichord Concerto in D Major, Wq. 43/2: II. Andante

06. Harpsichord Concerto in D Major, Wq. 43/2: III. Allegretto

07. Harpsichord Concerto in E-Flat Major, Wq. 43/3: I. Allegro

08. Harpsichord Concerto in E-Flat Major, Wq. 43/3: II. Larghetto

09. Harpsichord Concerto in E-Flat Major, Wq. 43/3: III. Presto

10. Harpsichord Concerto in C Minor, Wq. 43/4: I. Allegro assai

11. Harpsichord Concerto in C Minor, Wq. 43/4: II. Poco adagio

12. Harpsichord Concerto in C Minor, Wq. 43/4: III. Tempo di minuetto

13. Harpsichord Concerto in C Minor, Wq. 43/4: IV. Allegro assai

14. Harpsichord Concerto in G Major, Wq. 43/5: I. Adagio - Presto

15. Harpsichord Concerto in G Major, Wq. 43/5: II. Adagio

16. Harpsichord Concerto in G Major, Wq. 43/5: III. Allegro

17. Harpsichord Concerto in C Major, Wq. 43/6: I. Allegro di molto

18. Harpsichord Concerto in C Major, Wq. 43/6: II. Larghetto

19. Harpsichord Concerto in C Major, Wq. 43/6: III. Allegro

Bach started to compose the “6 Concerti per il cembalo concertato” Wq 43 at the end of 1770, 2 years after moving to Hamburg and succeeding his godfather Telemann, who died on June 25th 1767, as Kapellmeister at Hamburg’s Johanneum.

Their publication by Breitkopf was advertised in the Hamburg press on November 25th 1772. The concertos were designed to be widely accessible and described as “leicht”, easy, a term that lends itself to different interpretations.

The “ease” of these concertos does not just concern the instrumental and technical aspect, nor the form in which they were conceived.

Rather, the appeal of this “ease” lies in their accessibility to amateur and professional musicians who will perform them, for a number of reasons.

Firstly, all the parts of the various instruments are written in such a way as to allow the keyboard player to perform the concertos solo, without accompaniment.

J.S. Bach and W.F. Bach had already written both solo keyboard concertos without orchestra and transcriptions of their own as well as other authors’ original concertos. In this way, C.P.E. Bach continues a family tradition.

Secondly, some passages are provided with fingering. Bach the teacher, who had published the first part of the “Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen” in 1753, gave some very interesting suggestions of fingerings.

Lastly, the solo cadences are not left to the freedom of the interpreter, but they are written in full.

This way Bach shows a double character of his philosophy as a composer and interpreter. On the one hand, in fact, in his Versuch, Bach guides the reader towards the foundations of improvisation, improvised cadence and free fantasia; on the other hand, however, aware of the great variety of styles of his time, he is determined to give a very clear guide and a reading of the score that allows for the fewest possible misunderstandings.

In fact he writes in his Versuch:

“Composers, in order to ensure a good performance, should add the embellishments so as not to leave room for doubt, instead of abandoning their compositions to the whims of the performers”

“What is a good interpretation? EXCLUSIVELY the ability to make the ear perceive, by singing or playing, THE REAL CONTENT AND THE TRUE FEELING OF A MUSICAL COMPOSITION. By changing the interpretation, a passage can be expressed in so many different ways so as to change meaning and become unrecognizable. […] A good interpretation can be recognized if, when listening, all the notes appear without heaviness and the relative embellishments are well proportioned at the right moment, performed with the appropriate strength, with well-proportioned accents and IN COMPLIANCE WITH THE TRUE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PIECE: clarity and expressiveness correspond to this sweet, pure and flowing way of playing “

A NIGHT WITH C.P.E. BACH: CHARLES BURNEY’S TESTIMONY

In October 1772, Charles Burney had the chance to meet Bach, whose fame had already preceded him. The meeting with Bach, as he described it in his “Musical Tours”, is worth quoting:

“Hamburg is not at present, possessed of great eminence, except Carl Philip Emanuel Bach; but he is a legion! I had long contemplated, with the highest delight, his elegant and original compositions; and they had created in me so strong desire to see, and to hear him, that I wanted no other musical temptation to visit this city. […] It must be owned, that the style of this author is so uncommon, that a little habit is necessary for the enjoyment of it; Quintilian made a relish for the works of Cicero the criterion of a young orator’s advancement in his studies; and those of C.P.E. Bach may serve as a touchstone to the taste and discernement of a young musician. Complaints have been made against his pieces, for being long, difficult, fantastic, and far-fetched. In the first particular, he is less defensible than in the rest; Yet the fault will admit of some extenuation; for length, in a musical composition, is so much expected in Germany, that an author is thought barren of ideas, who leaves off till every thing has been said which the subject suggests.

Easy and difficult, are relative terms; what is called a hard word by a person of no education, may be very familiar to a scholar: our author’s works are more difficult to express, than to execute. As to their being fantastical, and far-fetched, the accusation, if it be just, may be softened, by alledging, that his boldest strokes, both of melody and modulation, are always consonant to rule, and supported by learning; and his flights are not the wild ravings of ignorance or madness, but the effusions of cultivated genius. His pieces, therefore, will be found, upon a close examination, to be so rich in invention, taste, and learning, that, with all the faults due to their charge, each line of them, if wire-drawn, would furnish more ideas than can be discovered in a whole page of many other compositions that have been well received by the public.”

A day with C.P.E. Bach

“When I went to his house […] the instant I entered, he conducted me up stairs, into a large and elegant music room, furnished with pictures, drawings, and prints of more than a hundred and fifty eminent musicians […] M. Bach was so obliging as to sit down to his Silbermann clavichord, and favourite instrument, upon which he played three or four of his choicest and most difficult compositions, with the delicacy, precision, and spirit, for which he is so justly celebrated among his countrymen. In the pathetic and slow movements, whenever he had a long note to express, he absolutely contrived to produce, from his instrument, a cry of sorrow and complaint, such as can only be effected upon the clavichord, and perhaps by himself.

After dinner, which was elegantly served, and chearfully eaten, I prevailed upon him to sit down again to a clavichord, and he played, with little intermission, till near eleven o’ clock at night. During this time, he grew so animated and possessed, that he not only played, but looked like one inspired. His eyes were fixed, his under lip fell, and drops of effervescence distilled from his countenance. He said, if he were to be set to work frequently, in this manner, he should grow young again. He is now fifty-nine, rather short in stature, with black hair and eyes, and brown complexion, has a very animated countenance, and is of a chearful and lively disposition.

His performance to-day convinced me of what I had suggested before from his works; that he is not only one of the greatest composers that ever existed, for keyed instruments, but the best player, in point of expression; for others, perhaps, have had as rapid execution: however, he possesses every style; though he chiefly confines himself to the expressive. He is learned, I think, even beyond his father, whenever he pleases, and is far before him in variety of modulation; his fugues are always upon new and curios subjects, and treated with great art as well as genius.”

That same night Burney had the privilege of listening to Bach play his 6 concertos on the clavichord:

“He played to me, among many other things, his last six concertos, lately published by subscription, in which he has studied to be easy, frequently I think at the expence of his usual originality; however, the great musician appears in every movement, and these productions will probably be the better received, for resembling the music of this world more than his former pieces, which seem made for another region, or at least another century, when what is now thought difficult and far-fetched, will, perhaps, be familiar and natural.”

Their publication by Breitkopf was advertised in the Hamburg press on November 25th 1772. The concertos were designed to be widely accessible and described as “leicht”, easy, a term that lends itself to different interpretations.

The “ease” of these concertos does not just concern the instrumental and technical aspect, nor the form in which they were conceived.

Rather, the appeal of this “ease” lies in their accessibility to amateur and professional musicians who will perform them, for a number of reasons.

Firstly, all the parts of the various instruments are written in such a way as to allow the keyboard player to perform the concertos solo, without accompaniment.

J.S. Bach and W.F. Bach had already written both solo keyboard concertos without orchestra and transcriptions of their own as well as other authors’ original concertos. In this way, C.P.E. Bach continues a family tradition.

Secondly, some passages are provided with fingering. Bach the teacher, who had published the first part of the “Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen” in 1753, gave some very interesting suggestions of fingerings.

Lastly, the solo cadences are not left to the freedom of the interpreter, but they are written in full.

This way Bach shows a double character of his philosophy as a composer and interpreter. On the one hand, in fact, in his Versuch, Bach guides the reader towards the foundations of improvisation, improvised cadence and free fantasia; on the other hand, however, aware of the great variety of styles of his time, he is determined to give a very clear guide and a reading of the score that allows for the fewest possible misunderstandings.

In fact he writes in his Versuch:

“Composers, in order to ensure a good performance, should add the embellishments so as not to leave room for doubt, instead of abandoning their compositions to the whims of the performers”

“What is a good interpretation? EXCLUSIVELY the ability to make the ear perceive, by singing or playing, THE REAL CONTENT AND THE TRUE FEELING OF A MUSICAL COMPOSITION. By changing the interpretation, a passage can be expressed in so many different ways so as to change meaning and become unrecognizable. […] A good interpretation can be recognized if, when listening, all the notes appear without heaviness and the relative embellishments are well proportioned at the right moment, performed with the appropriate strength, with well-proportioned accents and IN COMPLIANCE WITH THE TRUE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PIECE: clarity and expressiveness correspond to this sweet, pure and flowing way of playing “

A NIGHT WITH C.P.E. BACH: CHARLES BURNEY’S TESTIMONY

In October 1772, Charles Burney had the chance to meet Bach, whose fame had already preceded him. The meeting with Bach, as he described it in his “Musical Tours”, is worth quoting:

“Hamburg is not at present, possessed of great eminence, except Carl Philip Emanuel Bach; but he is a legion! I had long contemplated, with the highest delight, his elegant and original compositions; and they had created in me so strong desire to see, and to hear him, that I wanted no other musical temptation to visit this city. […] It must be owned, that the style of this author is so uncommon, that a little habit is necessary for the enjoyment of it; Quintilian made a relish for the works of Cicero the criterion of a young orator’s advancement in his studies; and those of C.P.E. Bach may serve as a touchstone to the taste and discernement of a young musician. Complaints have been made against his pieces, for being long, difficult, fantastic, and far-fetched. In the first particular, he is less defensible than in the rest; Yet the fault will admit of some extenuation; for length, in a musical composition, is so much expected in Germany, that an author is thought barren of ideas, who leaves off till every thing has been said which the subject suggests.

Easy and difficult, are relative terms; what is called a hard word by a person of no education, may be very familiar to a scholar: our author’s works are more difficult to express, than to execute. As to their being fantastical, and far-fetched, the accusation, if it be just, may be softened, by alledging, that his boldest strokes, both of melody and modulation, are always consonant to rule, and supported by learning; and his flights are not the wild ravings of ignorance or madness, but the effusions of cultivated genius. His pieces, therefore, will be found, upon a close examination, to be so rich in invention, taste, and learning, that, with all the faults due to their charge, each line of them, if wire-drawn, would furnish more ideas than can be discovered in a whole page of many other compositions that have been well received by the public.”

A day with C.P.E. Bach

“When I went to his house […] the instant I entered, he conducted me up stairs, into a large and elegant music room, furnished with pictures, drawings, and prints of more than a hundred and fifty eminent musicians […] M. Bach was so obliging as to sit down to his Silbermann clavichord, and favourite instrument, upon which he played three or four of his choicest and most difficult compositions, with the delicacy, precision, and spirit, for which he is so justly celebrated among his countrymen. In the pathetic and slow movements, whenever he had a long note to express, he absolutely contrived to produce, from his instrument, a cry of sorrow and complaint, such as can only be effected upon the clavichord, and perhaps by himself.

After dinner, which was elegantly served, and chearfully eaten, I prevailed upon him to sit down again to a clavichord, and he played, with little intermission, till near eleven o’ clock at night. During this time, he grew so animated and possessed, that he not only played, but looked like one inspired. His eyes were fixed, his under lip fell, and drops of effervescence distilled from his countenance. He said, if he were to be set to work frequently, in this manner, he should grow young again. He is now fifty-nine, rather short in stature, with black hair and eyes, and brown complexion, has a very animated countenance, and is of a chearful and lively disposition.

His performance to-day convinced me of what I had suggested before from his works; that he is not only one of the greatest composers that ever existed, for keyed instruments, but the best player, in point of expression; for others, perhaps, have had as rapid execution: however, he possesses every style; though he chiefly confines himself to the expressive. He is learned, I think, even beyond his father, whenever he pleases, and is far before him in variety of modulation; his fugues are always upon new and curios subjects, and treated with great art as well as genius.”

That same night Burney had the privilege of listening to Bach play his 6 concertos on the clavichord:

“He played to me, among many other things, his last six concertos, lately published by subscription, in which he has studied to be easy, frequently I think at the expence of his usual originality; however, the great musician appears in every movement, and these productions will probably be the better received, for resembling the music of this world more than his former pieces, which seem made for another region, or at least another century, when what is now thought difficult and far-fetched, will, perhaps, be familiar and natural.”

Year 2019 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads