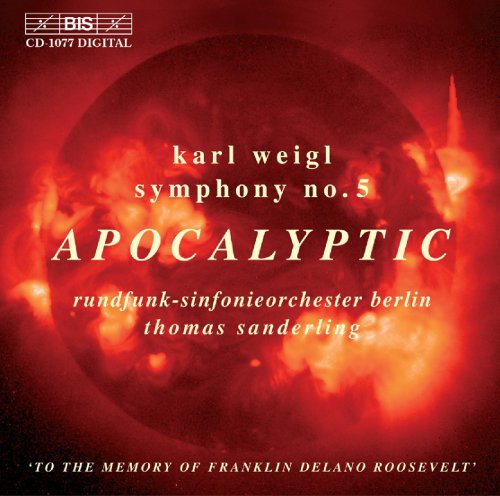

Thomas Sanderling - Karl Weigl: Symphony No. 5 "Apocalyptic Symphony" (2002)

- Title: Karl Weigl: Symphony No. 5 "Apocalyptic Symphony"

- Year Of Release: 2002

- Label: BIS

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (image + .cue, log, scans)

- Total Time: 64:24 min

- Total Size: 267 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

Symphony No. 5 ('Apocalyptic Symphony'):

1. I. Evocation (Moderato - Allegro moderato)

2. II. The Dance around the Golden Calf (Allegro moderato)

3. III. Paradise Lost (Adagio)

4. IV. The Four Horsemen (Allegro moderato)

5. Phantastisches Intermezzo, for orchestra, Op. 18

Symphony No. 5 ('Apocalyptic Symphony'):

1. I. Evocation (Moderato - Allegro moderato)

2. II. The Dance around the Golden Calf (Allegro moderato)

3. III. Paradise Lost (Adagio)

4. IV. The Four Horsemen (Allegro moderato)

5. Phantastisches Intermezzo, for orchestra, Op. 18

Karl Weigl’s music demonstrates once again that the great Austrian/German symphonic tradition did not die with Mahler, but continued to thrive well into the 20th century. Weigl (1881-1949) worked under Mahler in Vienna and enjoyed a fine reputation until, as we’ve heard often by now, the Nazi seizure of power, which forced his emigration to America where he died in comparative obscurity. He nevertheless composed a substantial body of orchestral and chamber music, including six symphonies. If this one is typical, it’s a legacy that urgently calls out for wider exposure.

Composed in 1945 and dedicated to the memory of President Roosevelt, the “Apocalyptic Symphony” received its premiere in 1968 under Stokowski. Although a couple of private tapes of that and at least one other performance exist, neither gives much sense of the impact that this magnificent work can have in concert. This splendid recording does. Weigl’s music offers the tonal richness and harmonic complexity of Franz Schmidt, with a healthy dose of Mahlerian irony and a brittle humor that calls to mind Berthold Goldschmidt. The symphony opens with a marvelous gesture: over the sounds of the orchestra tuning, the trombones blast out the first movement’s principal theme. Order having thus been established out of chaos, the music moves purposefully through a variety of predominantly dark moods to a stern conclusion.

The scherzo, subtitled “The Dance around the Golden Calf”, has a certain oriental quality, but much more noteworthy is its thematic workmanship, particularly the return of the trio section in a fortissimo outburst toward the end. The Adagio, headed “Paradise Lost”, must be ranked among the finest slow movements since Bruckner, whose rapt serenity and spiritual loftiness it effortlessly recalls. Get this disc for this movement alone: it’s a perfect example of music both of a specific tradition and effecting a new step forward for that same tradition. Distinguished by haunting melodies, evocative orchestration, and superbly gauged climaxes, it also confirms just how well trained this entire generation of composers really was, particularly in the confident use of a large and varied orchestra.

The finale, “The Four Horsemen”, is not what the title might lead you to expect, and it serves to caution listeners to pay attention to the music rather than to external descriptions. We’ll never really know exactly what this appellation may have meant to Weigl, but I have already seen a couple of stupid comments in print by “critics” who observe that the music doesn’t “sound” to them like the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, as if they would know! What matters, of course, is whether or not what Weigl actually composed works as the finale to his Fifth Symphony–and about that there can be no question. What we have here is a bitterly ironic march, leaving no doubt that Weigl sees the apocalypse in question not as a spiritual happening, but as man-made event. For 10 minutes the music marches on, pausing once for a glimpse back at Paradise Lost before the pealing of bells announces a conclusion as ambiguously triumphant as that of any Shostakovich symphony. It’s an inexorably “right” conclusion to a remarkable work.

The Phantastisches Intermezzo began life as part of the composer’s Second Symphony, but soon acquired an independent existence. More lightly scored than the Fifth Symphony, it’s a brilliant exercise in contrast, particularly with respect to chromatic vs. diatonic harmony. Scurrying wind figures and bustling strings alternate with Romantic-sounding brass fanfares. It’s a delight. Weigl’s orchestration shimmers brilliantly, and there’s absolutely nothing quite like it by anyone else.

The Berlin Radio Symphony and Thomas Sanderling deserve special credit for their effervescent performance of this gossamer-textured, extremely rapid and tiring piece. But then, they play both works with tremendous commitment. Sanderling clearly understands the special emotional world that the symphony’s Adagio inhabits; he and his players deliver the music with a hushed intensity that, more than any other factor, sets the seal on Weigl’s claim to musical greatness. Thrilling recorded sound, warm yet clear, captures the music’s complex textures with tactile immediacy. Don’t miss this stunning new release. -- David Hurwitz

Composed in 1945 and dedicated to the memory of President Roosevelt, the “Apocalyptic Symphony” received its premiere in 1968 under Stokowski. Although a couple of private tapes of that and at least one other performance exist, neither gives much sense of the impact that this magnificent work can have in concert. This splendid recording does. Weigl’s music offers the tonal richness and harmonic complexity of Franz Schmidt, with a healthy dose of Mahlerian irony and a brittle humor that calls to mind Berthold Goldschmidt. The symphony opens with a marvelous gesture: over the sounds of the orchestra tuning, the trombones blast out the first movement’s principal theme. Order having thus been established out of chaos, the music moves purposefully through a variety of predominantly dark moods to a stern conclusion.

The scherzo, subtitled “The Dance around the Golden Calf”, has a certain oriental quality, but much more noteworthy is its thematic workmanship, particularly the return of the trio section in a fortissimo outburst toward the end. The Adagio, headed “Paradise Lost”, must be ranked among the finest slow movements since Bruckner, whose rapt serenity and spiritual loftiness it effortlessly recalls. Get this disc for this movement alone: it’s a perfect example of music both of a specific tradition and effecting a new step forward for that same tradition. Distinguished by haunting melodies, evocative orchestration, and superbly gauged climaxes, it also confirms just how well trained this entire generation of composers really was, particularly in the confident use of a large and varied orchestra.

The finale, “The Four Horsemen”, is not what the title might lead you to expect, and it serves to caution listeners to pay attention to the music rather than to external descriptions. We’ll never really know exactly what this appellation may have meant to Weigl, but I have already seen a couple of stupid comments in print by “critics” who observe that the music doesn’t “sound” to them like the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, as if they would know! What matters, of course, is whether or not what Weigl actually composed works as the finale to his Fifth Symphony–and about that there can be no question. What we have here is a bitterly ironic march, leaving no doubt that Weigl sees the apocalypse in question not as a spiritual happening, but as man-made event. For 10 minutes the music marches on, pausing once for a glimpse back at Paradise Lost before the pealing of bells announces a conclusion as ambiguously triumphant as that of any Shostakovich symphony. It’s an inexorably “right” conclusion to a remarkable work.

The Phantastisches Intermezzo began life as part of the composer’s Second Symphony, but soon acquired an independent existence. More lightly scored than the Fifth Symphony, it’s a brilliant exercise in contrast, particularly with respect to chromatic vs. diatonic harmony. Scurrying wind figures and bustling strings alternate with Romantic-sounding brass fanfares. It’s a delight. Weigl’s orchestration shimmers brilliantly, and there’s absolutely nothing quite like it by anyone else.

The Berlin Radio Symphony and Thomas Sanderling deserve special credit for their effervescent performance of this gossamer-textured, extremely rapid and tiring piece. But then, they play both works with tremendous commitment. Sanderling clearly understands the special emotional world that the symphony’s Adagio inhabits; he and his players deliver the music with a hushed intensity that, more than any other factor, sets the seal on Weigl’s claim to musical greatness. Thrilling recorded sound, warm yet clear, captures the music’s complex textures with tactile immediacy. Don’t miss this stunning new release. -- David Hurwitz

Classical | FLAC / APE | CD-Rip

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads