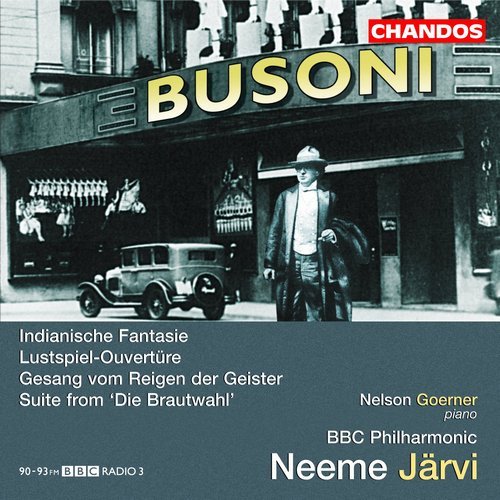

Nelson Goerner, BBC Philharmonic, Neeme Järvi - Busoni: Orchestral Works, Vol.2 (2005)

BAND/ARTIST: Nelson Goerner, BBC Philharmonic, Neeme Järvi

- Title: Busoni: Orchestral Works, Vol.2

- Year Of Release: 2005

- Label: Chandos Records

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

- Total Time: 64:34

- Total Size: 257 Mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

Ferruccio Busoni (1866–1924)

[1] Lustspiel-Ouvertüre, Op. 38 (1897, revised 1904)

[2] Indianische Fantasie, Op. 44 (1913–14)

for Piano and Orchestra

[3] Gesang vom Reigen der Geister, Op. 47 (1915)

Indianisches Tagebuch, Book II (Elegie No. 4)

[4]-[8] Die Brautwahl, Op. 45 (1912)

Suite for Orchestra

Performers:

Nelson Goerner, piano

BBC Philharmonic

Neeme Järvi, conductor

DOWNLOAD LINKS

Ferruccio Busoni (1866–1924)

[1] Lustspiel-Ouvertüre, Op. 38 (1897, revised 1904)

[2] Indianische Fantasie, Op. 44 (1913–14)

for Piano and Orchestra

[3] Gesang vom Reigen der Geister, Op. 47 (1915)

Indianisches Tagebuch, Book II (Elegie No. 4)

[4]-[8] Die Brautwahl, Op. 45 (1912)

Suite for Orchestra

Performers:

Nelson Goerner, piano

BBC Philharmonic

Neeme Järvi, conductor

Rarely have Busoni’s orchestral works been animated with such grasp, interpretive authority, and sheer executive brilliance. Passionate advocates haven’t lacked, but they’ve been hampered by second-string ensembles, incomprehension, expedience, and timorous interpretive gambits. Even Marc-André Hamelin’s otherwise splendid go at the Piano Concerto was marred by too often faceless, routine orchestral backup. In his biography of the composer, E. J. Dent notes, “A word which frequently occurs in his writings about music is sich auflösen—to melt or dissolve. He would have agreed with the poet that the ultimate function of music is to ‘Dissolve me into ecstasies/And bring all Heaven before mine eyes . . .’.” Maestro Järvi achieves this on occasion, rendering notes into spirit on the crest of playing that is never less than virtuosic, and it makes all the difference between hearing Busoni as a quaint footnote, a curiosity in the unfolding of Modernism, and one of its most distinctive voices—one of its makers.

As in Järvi’s first, similarly savvy, collection of Busoni’s orchestral works (Chandos 9920, Fanfare 26:1), the program reveals his mature style—the fruit of his final decade, rife with preternatural resonance—in the making. A manic tilt at the 1897 Lustspiel-Ouverture (in its 1904 revision), for instance, strips away its accustomed air of innocuous pseudo-Mozartean high spirits to expose a high voltage daring, which looks ahead two decades to Prokofiev’s “Classical” Symphony. With Die Brautwahl, composed between 1906 and 1911, we are on the cusp of Busoni’s stylistic crystallization as post-Romantic opulence is overtaken by luminous proto-Modern detachment barbed by a love of the bizarre and grotesque. It is a delightful comic opera—as rich in character as Le nozze di Figaro or Die Meistersinger—but sprawling and discursive, and always produced, when it is produced, with drastic cuts. The five-movement suite Busoni drew from it, playing nearly half-an-hour, affords a mesmerizing conspectus. From previous recorded performances, I confess, only the assembly of the love duet—spread over three scenes in the opera—seemed wholly satisfactory: Järvi makes a compelling, richly telling go of it beginning to end, placing it at the center of my affections. More revealing is the stylistic gap between the Indianische Fantasie of 1913/14 and the Gesang vom Reigen der Geister of 1915, which finds Busoni in full command of his highly personal, eldritch, allusive last manner. Both works are inspired by Native American themes, the former by melodies supplied by Busoni’s former pupil, the ethnographer Natalie Curtis, the latter—”song of the spirit dance”—by the dancing possession that overtook Western tribes about 1888 and whose suppression led to the massacre at Wounded Knee. (The incident is also the subject, by the way, of The Ghost Dancers, a pithy, moving, and utterly fascinating verse drama with music by contemporary poet, Alan Shaw—available on the Web.) The Indianische Fantasie has been dismissed as an old-fashioned Liszt-style rhapsody on themes already familiar from the four solo piano pieces forming the Indianisches Tagebuch, and it is a fact that their pentatonic cast lends them an air of campy Nativist cliché. But it is also true that part of the piece’s narrative draw is hearing Busoni’s strange, magus-like sensibility divine a poetry of the primordial from them, beset by startling ferocity and genuine weirdness. And it is true a fortiori from the present performance in which Argentine pianist Nelson Goerner, hand-in-glove with Järvi’s interpretive sagesse, delivers the piano’s running commentary with dazzling deftness. One’s indulgent smile at the beginning soon yields to captivation. From this to the Gesang vom Reigen der Geister was but a short step chronologically but a quantum leap from a music whose ties to the past cast it as new wine in an old bottle, so to speak, to a music of pure potent evocation.

What will Järvi do next? He is not merely at home in Busoni’s idiom; he is master of the house. Dare we hope for the Piano Concerto with Goerner? The Turandot music? The Nocturne symphonique? The Divertimento for Flute? The Romanze e scherzoso for piano and orchestra? Perhaps even Doktor Faust? Chandos has captured him with a spaciousness encompassing the panoramic vistas of the Indianische Fantasie and the chamber ensemble intimacy of the Gesang vom Reigen der Geister—detailed, rich, and glowingly immediate. Landmark. Indispensable. Urged upon you with enthusiasm and gratitude. – Adrian Corleonis

As in Järvi’s first, similarly savvy, collection of Busoni’s orchestral works (Chandos 9920, Fanfare 26:1), the program reveals his mature style—the fruit of his final decade, rife with preternatural resonance—in the making. A manic tilt at the 1897 Lustspiel-Ouverture (in its 1904 revision), for instance, strips away its accustomed air of innocuous pseudo-Mozartean high spirits to expose a high voltage daring, which looks ahead two decades to Prokofiev’s “Classical” Symphony. With Die Brautwahl, composed between 1906 and 1911, we are on the cusp of Busoni’s stylistic crystallization as post-Romantic opulence is overtaken by luminous proto-Modern detachment barbed by a love of the bizarre and grotesque. It is a delightful comic opera—as rich in character as Le nozze di Figaro or Die Meistersinger—but sprawling and discursive, and always produced, when it is produced, with drastic cuts. The five-movement suite Busoni drew from it, playing nearly half-an-hour, affords a mesmerizing conspectus. From previous recorded performances, I confess, only the assembly of the love duet—spread over three scenes in the opera—seemed wholly satisfactory: Järvi makes a compelling, richly telling go of it beginning to end, placing it at the center of my affections. More revealing is the stylistic gap between the Indianische Fantasie of 1913/14 and the Gesang vom Reigen der Geister of 1915, which finds Busoni in full command of his highly personal, eldritch, allusive last manner. Both works are inspired by Native American themes, the former by melodies supplied by Busoni’s former pupil, the ethnographer Natalie Curtis, the latter—”song of the spirit dance”—by the dancing possession that overtook Western tribes about 1888 and whose suppression led to the massacre at Wounded Knee. (The incident is also the subject, by the way, of The Ghost Dancers, a pithy, moving, and utterly fascinating verse drama with music by contemporary poet, Alan Shaw—available on the Web.) The Indianische Fantasie has been dismissed as an old-fashioned Liszt-style rhapsody on themes already familiar from the four solo piano pieces forming the Indianisches Tagebuch, and it is a fact that their pentatonic cast lends them an air of campy Nativist cliché. But it is also true that part of the piece’s narrative draw is hearing Busoni’s strange, magus-like sensibility divine a poetry of the primordial from them, beset by startling ferocity and genuine weirdness. And it is true a fortiori from the present performance in which Argentine pianist Nelson Goerner, hand-in-glove with Järvi’s interpretive sagesse, delivers the piano’s running commentary with dazzling deftness. One’s indulgent smile at the beginning soon yields to captivation. From this to the Gesang vom Reigen der Geister was but a short step chronologically but a quantum leap from a music whose ties to the past cast it as new wine in an old bottle, so to speak, to a music of pure potent evocation.

What will Järvi do next? He is not merely at home in Busoni’s idiom; he is master of the house. Dare we hope for the Piano Concerto with Goerner? The Turandot music? The Nocturne symphonique? The Divertimento for Flute? The Romanze e scherzoso for piano and orchestra? Perhaps even Doktor Faust? Chandos has captured him with a spaciousness encompassing the panoramic vistas of the Indianische Fantasie and the chamber ensemble intimacy of the Gesang vom Reigen der Geister—detailed, rich, and glowingly immediate. Landmark. Indispensable. Urged upon you with enthusiasm and gratitude. – Adrian Corleonis

DOWNLOAD LINKS

Classical | FLAC / APE | CD-Rip

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads